In autumn 2013 Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a new project—or geostrategic vision—now known as the BRI, which aroused consternation around the world. Soon after, the Chinese scientific and expert community revealed that this project was essentially about presenting China as a new global geostrategic player. Thus, returning to its previously held status as a great center of strength and ideas in the East.

The BRI was met with surprise and mixed feelings by the West. The most common response posited that a new heavy weight player had entered the world stage, which naturally aroused the greatest consternation from the USA—the current global hegemon. In the broader EU there are perceptions of new opportunities and possibilities arising from the BRI, however the details are still rather unknown. More often, and increasingly, the perception is that the Chinese vision has some serious faults and shortcomings.

The most serious of those is that the implementation of the BRI threatens the breakdown of the EU, which is amplified due to the lack of a coherent EU strategy towards the BRI and China. Another concern is the severe FDI asymmetry (€35b to €7.7b) present between China and Europe. Finally, Chinese investors have failed to engage in greenfield investments in Europe.

The BRI implementation has created a completely new dynamic in Sino-EU relations, requiring new consideration, reflection and a real strategy. The EU’s strategic alliance with the USA must also always be kept in mind during this process. For Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries, the vision of BRI is entangled with China’s 16+1 initiative, which was launched prior to BRI and was intended to enhance cooperation between these countries and the PRC.

Originally, the Chinese side in the 16+1 proposed a vision of “12 projects,” or steps, and allocated a sum of $10b for this purpose. However, few of these plans have been successfully implemented, due in part to cooperation problems between the EU and China.

Despite strategic changes to the focus of the initiative in 2016, the level of political cooperation still precedes the level of economic exchange. Nonetheless, the most notable achievements so far include annual summits and the establishment of the China-CEE Institute in Budapest.

The state of research available so far shows that the countries of the CEE region, like the countries of the whole EU, are quite divided about Chinese initiatives. The investment cooperation, which forms the center of Chinese proposals and interests, has not brought the expected results so far. Moreover, in the CEE region there is a disparity in investment, with the V4 countries playing a leading role—sharing over 62% of all Chinese investment.

As for the political aspects, the current 16+1 cooperation runs almost exclusively on bilateral agreements between each country and China, and does not improve regional cooperation. In this state of affairs, only Hungary and Serbia exhibit clear political will for cooperation with China.

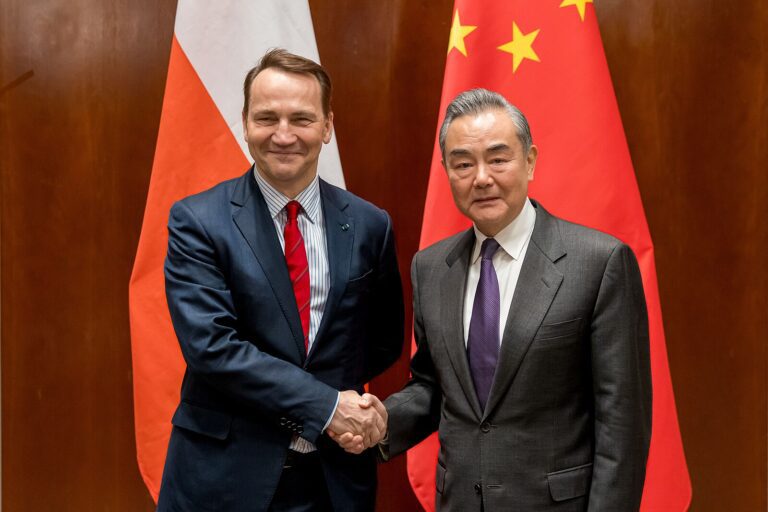

For Poland, the BRI became the focus its foreign policy. Poland is located on the main land axis of the Silk Road from China to Western Europe, what is an inalienable asset in relations with China. It would be wise to use this asset properly, yet, so far, both have achieved little success in the economic sphere, unlike the comparative successes in their diplomatic relations.

Sino-Polish relations were relatively meager during the 1990s and 2000s and only began to improve around the turn of this decade. This growth peaked in June 2016, when the two nations raised the status of bilateral relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership. Unfortunately, the agreements accompanying this status upgrade, and more since, either were not implemented or significantly slowed down. Relations were not as smooth as expected, with some landmark government decisions going against China.

Instead, China began to conduct agreements in Poland at the local level, dealing mostly with self-government authorities. Poland now plays a pioneering regional role in improving trade relations through the railway sector. It is estimated that by the end of 2017, approximately 25 percent of all goods arriving by rail to the EU came through Poland. Rail traffic between China and the EU has increased a hundredfold over the past decade.

Despite various negative perceptions, the BRI still offers many potential benefits to the CEE region. Aside from the development of rail infrastructure, the energy sector has received some Chinese tenders. There are contracts for powerplants in Romania (€7b), the Czech Republic (€15b) and Bulgaria.

The BRI and 16+1 combined mean that Poland’s unique location is an incredible asset. Therefore, it not only can, but should engage with China. The degree of this commitment should be constantly measured, though, due to China’s power asymmetry.

On the negative side, the relational asymmetry that all CEE countries face with China is a fundamental problem. In economics, this is exemplified by widespread trade deficits. In 2016, Chinese exports to CEE totaled $65.17b while CEE exports to china were just $9.72b.

Furthermore, China’s rapid growth towards superpower status means that relations with it require deep geostrategic reflection. Closer relations with China may arouse suspicion in major allies and partners like the US and Germany. It is therefore concerning that nearly every CEE country lacks any specific strategy towards China. In Poland, regular analyses of China are carried out, at a comprehensive, but so far insufficient level. It would be in Polish national interests to establish a special team or institute dealing exclusively in this area.

From now on, relations with China have an impact on the balance of power in the world and should be treated as such. Increased Sino-CEE and Sino-Polish cooperation must be balanced with numerous considerations regarding potential risks.

Nevertheless, the large-scale concept of the BRI will continue to be pushed through CEE by Beijing, and Poland is considered an important partner in these calculations. It would be wise for Poland to use its considerable advantages properly. There is potential for this, all that is needed is imagination and the accompanying political will.

Written by

Bogdan Góralczyk

b_goralczykProfessor Bogdan J. Góralczyk is a political scientist and sinologist. He currently serves as the director of the Centre for Europe at the University of Warsaw. He is the former Ambassador of Poland to Thailand and head of the Polish diplomatic missions to Burma and the Philippines.