Oxford-style Debate: Should the 16+1 Dissolve?

Motion: „16+1 is a China-led initiative which does not bring any benefits for the participating 16 CEE countries, thus it should dissolve”

FOR the motion:

MARCIN PRZYCHODNIAK

Analyst, PISM

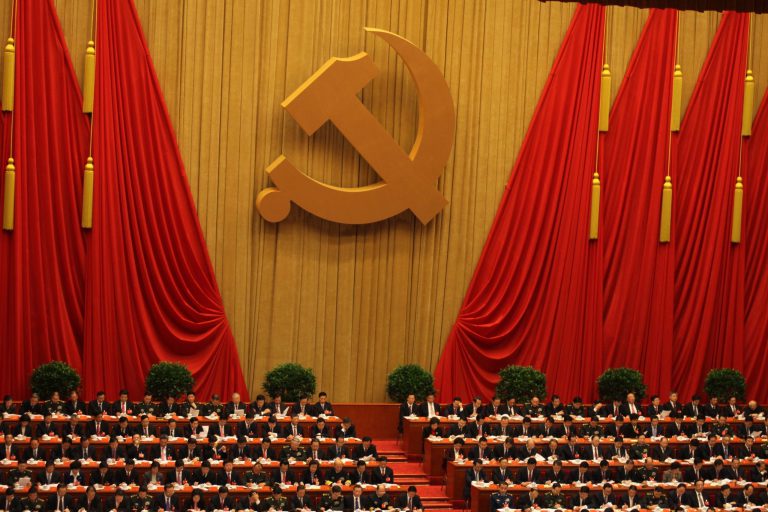

The 8th summit of Heads of Government of Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) and Chinese PM Li Keqiang will start tomorrow in the Croatian city of Dubrovnik. Such a location is of course symbolic, but not only because of the significance of the Peljesac bridge which was built by a Chinese company, with EU funding involved, and in an EU member state. The investment projects in the Balkans (on a bilateral not regional basis) are becoming a main part of the “16+1” cooperation and as such will be often highlighted by the Chinese during the Dubrovnik meeting. It is a clear symbol of “16+1” – a China-led initiative serving Chinese interests and harming, or at least impeding, the interests of other participants, especially EU member states in their relations with the U.S and links with EU power circles.

1. The “16+1” is an initiative with mechanisms and procedures based on the widely implemented “South-South” model of Chinese foreign policy and economic cooperation. It has not only been used in Central and Eastern Europe but also in Africa and South-East Asia. Since the foundation of “16+1” in 2012, the Chinese policy evolved and mixed its priorities and working mechanisms, but China always followed its interests in Central and Eastern Europe, despite the rhetoric of “win-win” or “mutual interests”.

2. There is no regional economic cooperation, which was originally thought to become the basis and main agenda of the “16+1” initiative. The multilateral aspect of investment projects is almost non-existent, with an expensive and unfinished Budapest-Belgrade railway serving as the only example (but the project again runs on a “China+1” basis). This may be in part because of the EU’s (especially EEAS’s) reservations towards such regional cooperation that undercuts the existing EU-China relations and the accompanying working mechanisms and definitions.

3. Such a model of “South-South” cooperation actually preserved the negative image of China-CEE cooperation within Chinese society and its power apparatus. Following an established stereotype, CEE is oriented not towards regional development and high-tech modernization, but hard infrastructure construction involving Chinese state loans and enterprises. It strengthens the long-time existing differences in China’s attitude towards Western and CEE countries and preserves stereotypes of developmental and civilizational divisions within the EU.

4. “16+1” has always been China-led and the People’s Republic of China is an instrumental and key-member of the initiative. There was never equality between partners, which is highly visible if you consider the issue of including new participants (Ukraine, Austria, Greece). Such ideas were rejected by China without any real consultations with partners and open explanations coming from the Chinese MFA.

5. None of the Chinese economic offers made during the past seven years of the “16+1” initiative were actually economically interesting for EU member states, something which would justify a growing involvement in the initiative. Chinese state loans that were offered were too expensive compared to the existing EU funds (for some countries even the possible release of their own bonds to finance investment could be cheaper in terms of interest rates). Chinese loans are thus not only economically disputable but also politically controversial.

6. The level of investment announced during Xi Jinping’s visits to participants of “16+1” (e.g. Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland) was not delivered in substance and quality. And if it was (partially) delivered, controversial enterprises such as CEFC in the Czech Republic were involved. The negative trade balances of participating countries (although complicated and not entirely easy to present with accuracy) are also a part of the negative complex in the summary of “16+1”.

7. The political benefits coming out of the “16+1”, described as another platform of political communication and high-level political contacts with China, are overestimated. Such summits serve rather politically as an opportunity for Chinese leaders to present their importance and influence over the participating states. The timing and conditions of possible bilateral meetings on the sidelines of the summits with PM Li Keqiang are limited and orchestrated – it practically leaves no space for a serious exchange of topics. It also hurts the political bilateral cooperation of certain members with China.

8. The “16+1” initiative is still being used by China as an important tool of influence towards the EU in general, especially Germany. This is also important if we consider the recent radicalization of the EU’s language in published EC recommendations on cooperation with China as well as the accomplishments of the recent EU-China summit. The context of 5G construction, Huawei’s involvement and problems in the transatlantic agenda constitute an important part of these discussions. The “16+1” initiative is still used by less-informed participants of the European political debate as an example of China’s “divide and rule” policy. Given the minimal Chinese investment and influence coming from trade, real Chinese leverage is rather based on the political ambitions of certain entities in the participating countries.

9. The “16+1” initiative can still be perceived as an important Chinese tool in its growing cooperation with the Balkan states (most of these countries are already negotiating and aspiring to join the EU). For the Balkan states, engagement in the initiative could provide the needed investment and capital. It is also a short-term gain in areas such as infrastructure building, but in general, it is a long-term loss. Cooperation with China negatively influences the process of legislation screening and adjustment of countries and their local laws to EU regulations, which is a necessary condition for their future membership in the EU.

These arguments can certainly prove that the “16+1” initiative neither provides participants with real and substantial benefits, nor could it explain the growing political costs – especially for eleven EU member states. Growing numbers of tourists or think-tank exchanges hardly suffice as a justification for “16+1” platform’s existence.

AGAINST the motion:

ANASTAS VANGELI

Assistant Professor, University of Ljublana

I argue that participation in the 16+1 format makes a lot of sense and brings a number of opportunities to Central, Eastern and Southeastern European (CESEE) countries.16+1 is a China-led cooperation format in which the CESEE countries participate voluntarily. 16+1 enables them to exercise agency on the international stage by interacting with the second largest economy in the world: it is an opportunity that they did not have before. While Western Europeans were deepening and profiting from their linkages with China in the 1990s and 2000s, the CESEE countries lacked the desire, knowledge or resources to follow suit. Today, despite the firmer attitudes in the EU, there is a strong economic interdependence between Western Europe and China (who have the most significant trade relationship in the world), while the volume of CESEE-China economic exchange remains relatively small. 16+1 is where policymakers and experts contemplate solutions about how to increase it; dialogue is the main purpose of the format and therefore it should not be dissolved.

1. 16+1 is convened by China, but the CESEE countries are not bystanders – they use the situation to advance their interests. To ask China to dissolve 16+1 is to surrender all power to Beijing and infantilize the CESEE countries as weak and unable to live up to the role of autonomous actors in global politics. Instead, 16+1 should be seen as a chance for CESEE governments to actively engage with China and coordinate with each other. Those dissatisfied with the 16+1 format could, for example, deliver sharp statements or withdraw from joint documents – or be proactive and drive the cooperation according to their agenda.

2. So far, no one is leaving 16+1. There is a certain compatibility between what China offers through 16+1 and the BRI, and what CESEE countries need. Some are EU members and others are candidates; some are more developed than the others; some have second thoughts on liberal democracy while others do not; but what is common for all of the sixteen is that they are post-socialist, “dependent capitalist” economies that require massive inflows and impulses from outside in order to be sustained. With 16+1, China becomes one of the stakeholders (but certainly not the most important one) in their future development. The high expectations from the cooperation with China voiced by many in CESEE reveal that the Chinese narrative has found its audience in the region. 16+1 is a channel to translate these expectations into policy.

3. 16+1 is a loosely institutionalized coordination platform, but it lacks implementation mechanisms. It helps in the facilitation of inter-governmental and business deals, but there is a limit of what can be achieved through the platform itself. The participation of CESEE countries in the platform should not be seen in isolation, but rather in sync with other processes that contribute to tangible outcomes (bilateral/multilateral inter-governmental deals, market forces, structural factors). A key variable in all of this is not only China’s actions but the agency of the CESEE actors themselves – they both matter for successes or lack thereof.

4. Today some CESEE actors are more satisfied with their cooperation with China than others. Balkan countries, which are less developed than other CESEE countries (where catching up with the rest of Europe may take up to two centuries) have received infrastructure projects and inflows towards the revitalization of the old and opening of new industrial capacities. However, overall investment and trade are on the rise in the sixteen. There are success stories in Croatia and Bulgaria; even in ‘skeptical’ countries like Poland, there are success cases at the subnational level (e.g. Lodz). Of course, challenges of trade imbalances and below-than-expected greenfield investments remain – but it would be a mistake to write off 16+1 as a failure. In fact, 16+1 provides a venue where various challenges are discussed.

5. Contrary to alarmist reports, academic research has so far found little evidence of China using 16+1 as a vehicle to advance its political goals in CESEE and Europe as a whole. The CESEE countries have not turned into Beijing’s pawns – the leverage of the EU and NATO in the region is too strong to be challenged. Moreover, Chinese actors demonstrate that they do not necessarily work to the detriment of EU norms and standards – they also learn and adjust to EU regulations, as the case of the Pjelesac Bridge tender shows. 16+1 thus gives CESEE and other European actors an opportunity to make China play by their rules.

6. China has contributed to the diversification of economic thinking. Connectivity, infrastructure megaprojects, state-led development, and new regionalist ideas are slowly becoming a part of the mainstream in CESEE, partially due to its interaction with China. Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia and Greece have established the Varna 4 to pursue regional connectivity; Poland has its Amber Road and follows Justin Yifu Lin’s “New Structural Economics,” and so on. These developments somewhat challenge the neoliberal hegemony in Europe – which, however, is not necessarily a bad thing: post-crisis Europe needs alternative visions for growth, and China as a partner-come-competitor can stimulate new thinking. Sometimes China-induced indulgence in geo-economic imagination also has therapeutic effects on some CESEE actors, especially if one compares the 16+1 and BRI experiences to the European debates focused on multiple crises, fears and uncertainties, and the protectionist discourse of Trump’s US presidency.

7. 16+1 awakens the geo-economic imagination beyond CESEE. Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Greece, Ukraine, and Belarus have closely followed 16+1 and participated as “observers” at the high-level events, and some of them have even expressed a desire to join the format. German-CESEE-Chinese cooperation, as well as Nordic-Baltic-Chinese cooperation remain possibilities too. This all paves the way for exploring further avenues of cooperation, that may not have existed otherwise, and should also be taken advantage of.

With all eyes on the summit in Dubrovnik, it is up to the CESEE governments themselves to seize the opportunity so they can establish their own narrative of 16+1, avoid being caught in the cross-fire of geopolitical competition, further exercise their agency on the global stage, and closely coordinate between each other.

Written by

Marcin Przychodniak

Molos123Marcin Przychodniak is an Analyst at Asia-Pacific program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), focusing on Chinese politics and a former diplomat in Beijing.

Anastas Vangeli

Anastas Vangeli is currently a second year PhD researcher at the Graduate School for Social Research at the Polish Academy of Science (PAN) in Warsaw, and a Claussen-Simon PfD Fellow at the Trajectories of Change Program of the ZEIT – Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius