The research and publication have been supported by a grant from the European Dialogue Program of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation (FNF Europe). The Association for International Affairs (AMO) gratefully acknowledges the valuable research assistance of Emilia Carson, a former AMO intern; a former colleague who, owing to current professional commitments, prefers to remain anonymous; and Nele Fabian and Katharina Osthoff for their insightful comments on an early draft of the article.

Brussels is, by design, a place where interests meet. The EU’s regulatory decisions reach deep into markets and public policy, so it is common practice that companies, industry associations, NGOs, think tanks, and diplomatic missions invest time in explaining their positions to the EU decision-makers. Much of this activity is legitimate and often useful: it helps policymakers test assumptions, consider nuances, and hear from those who will be affected. At the same time, the density of lobbying and advocacy in Brussels makes transparency an essential condition for public trust – especially on politically sensitive files, including those related to China.

Within this ecosystem, Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) occupy a distinctive role. They are the EU’s only directly elected lawmakers, working through committees and political groups to amend and adopt legislation, scrutinize the European Commission, and shape policies through debates and motions. MEPs’ offices also function as policy hubs: they receive briefings and meet a wide range of stakeholders seeking to provide expertise or advance particular preferences. Understanding who gains access to these offices – and on which issues – adds an important layer to how we read parliamentarians’ stances on China beyond the visible endpoint of votes on China-related motions in the European Parliament.

AMO therefore examined publicly disclosed meeting records by MEPs and their Accredited Parliamentary Assistants (APAs) with China-linked stakeholders during the previous parliamentary term (2019–2024) and at the beginning of the new mandate, through November 2024. Rather than treating meetings as evidence of influence, the analysis uses them as a transparency-based lenses on patterns of engagement showing where attention concentrated, which institutional roles attracted higher volumes of contact, and which China-linked actors most frequently sought access to MEPs.

Who China Met in Brussels

The authors built the dataset by scraping the meeting records published on MEPs’ individual European Parliament profile pages, capturing all declared meetings with stakeholders with verified links to China and Hong Kong and, for comparison, Taiwan. The data were filtered using keywords such as country name, company name, and other terms deemed relevant (e.g., Mandarin, Confucius) in multiple European languages to account for different variations. Different data formats that MEPs used to input their meetings made it challenging to obtain all the data. Thus, the following analysis should be taken as indicative rather than exhaustive, offering a representative snapshot of engagement patterns rather than a complete record. To contextualize the disclosure data and the MEPs’ practice in recording meetings, the authors also conducted semi-structured interviews with around two dozen current and former MEPs, APAs, and EP observers during a field trip in Brussels in October 2024.

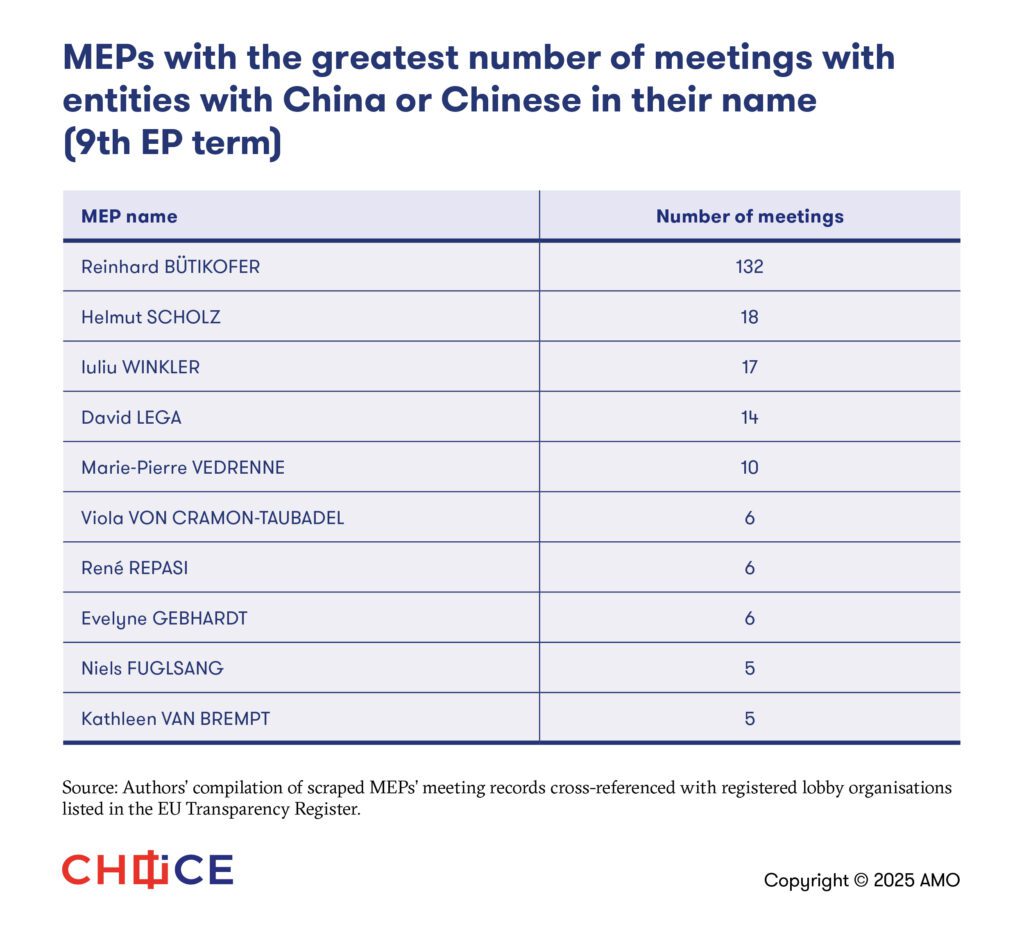

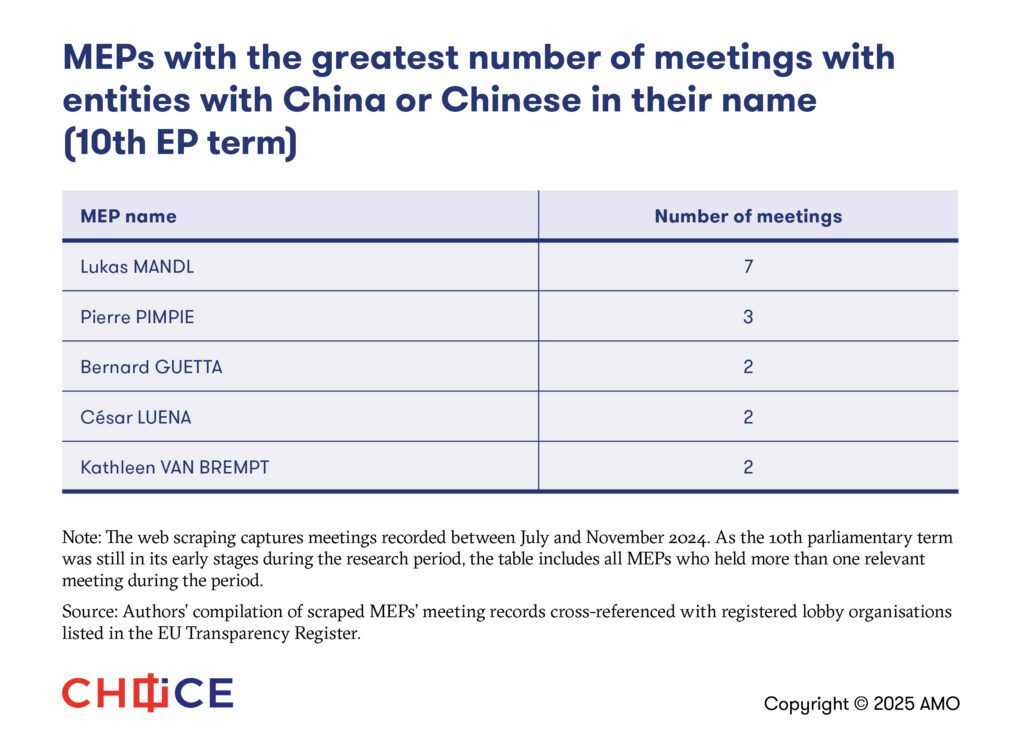

The collected data indicate that during the 9th parliamentary term (2019-2024), 228 MEPs formally reported meetings with China-linked stakeholders. As of November 2024, during the 10th term, 75 MEPs have registered meetings with relevant stakeholders. Usually, the number of registered meetings per MEP ranges between one and 10 meetings per term. However, there are several outliers.

Two outliers draw attention: Lukas Mandl from the Österreichische Volkspartei (Austrian People’s Party), belonging to the EPP, during both EP terms; and Reinhard Bütikofer, who was a MEP from Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (Alliance 90/The Greens) belonging to Greens/EFA during the 9th term. It is important to stress that, while certain MEPs recorded a notably higher number of meetings with interest groups affiliated with China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan, such frequency should not be automatically interpreted as an indicator of political alignment or favorable sentiment. Rather, it is essential to consider the positions MEPs held during their parliamentary terms. For example, memberships in the Committee on Foreign Affairs, the Delegation for Relations with the People’s Republic of China, or the Committee on International Trade inherently entail more frequent interactions with third-country representatives, including those from China. Similarly, elevated levels of recorded engagement may be attributable to the fact that some MEPs served as rapporteurs or co-rapporteurs for motions concerning China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan. In such cases, the drafting process could require consultations with a broader range of stakeholders, thereby increasing the number of registered meetings.

Moreover, it is also important to note a potential paradox: MEPs and APAs who comply with transparency requirements by reporting their meetings may appear to engage more frequently with foreign actors than those who do not. Conversely, individuals who fail to disclose such interactions may be perceived – perhaps incorrectly – as having had no contact with external stakeholders. Thus, caution is needed in interpreting the findings, as the available data may reflect differences in reporting practices rather than actual engagement levels.

Throughout both terms the majority of registered meetings were conducted with stakeholders affiliated with China, while there were fewer meetings with representatives of Hong Kong-affiliated interest groups. Most recorded meetings were held with the Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the European Union, as well as with Chinese diplomatic missions accredited to individual EU member states.

Regarding meetings with representatives of the Taipei Representative Office in the European Union and Belgium, as well as missions to individual EU member states, 33 MEPs engaged with them on more than one occasion during the 9th parliamentary term. As in the case of interactions with Chinese representatives, MEP Reinhard Bütikofer recorded the highest number of meetings with Taiwanese officials.

Huawei and TikTok Led in the Number of Meetings

The data on meetings with companies were cross-referenced with the EU Transparency Register which was set up as part of the EU’s efforts to increase its transparency, credibility, and accountability and as a response to large-scale lobbying activities by a wide range of actors. Since 2021, it has been mandatory for all lobbying groups to register in the EU Transparency Register in order to be able to interact with EU lawmakers. As of 2024, around 12,500 lobbying groups had registered themselves. Moreover, since 2023, all MEPs and their APAs have been required to record scheduled meetings with lobbying groups regarding activities related to the EP on the MEPs’ online pages.

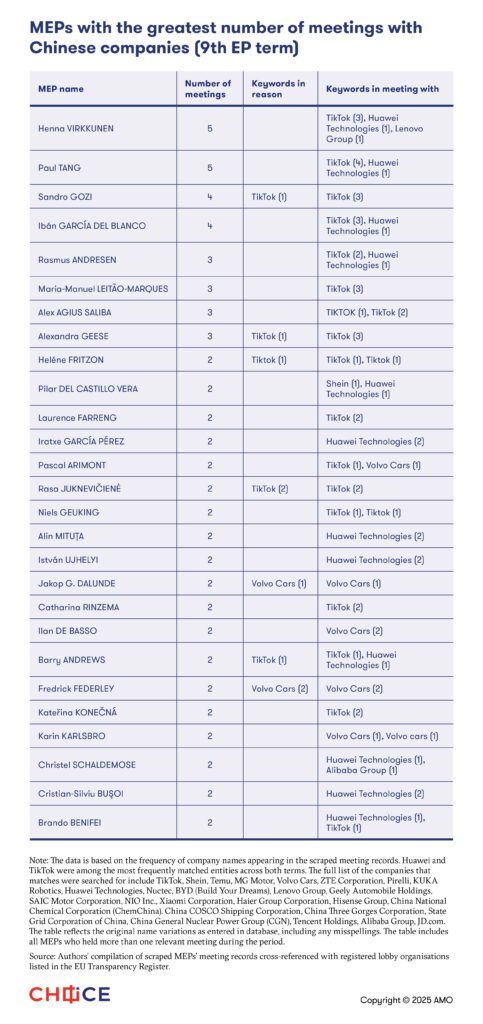

Following the Qatargate scandal, MEPs have become more careful about which interest groups they meet. Yet, according to one of our interviewees, even though the EP sent out an email warning about Huawei’s lobbying activities, many MEPs, APAs, and other staffers were still willing to openly meet with Huawei’s representatives. In fact, during the 9th term, 29 MEPs recorded a total of 33 meetings with Huawei representatives, while between July and November 2024, nine MEPs reported meetings with Huawei.

Notably, Huawei was among the companies that the MEPs met with most frequently, both in the 9th and in the beginning of the 10th term. The documented purposes of the meetings encompass a broad array of topics, including 5G security in Europe, exchanges on cybersecurity, discussions on the Artificial Intelligence Act, stakeholder consultations, and current affairs.

Another frequently appearing company across both European Parliament terms was TikTok. The MEPs’ stated reasons for meetings with TikTok vary and include, but are not limited to, discussing child protection on social media platforms, political content regulation, cyberbullying and deepfakes, and the role of social media in electoral campaigns. While meetings with Alibaba and Volvo Cars also appear in the records, they are significantly less common than those involving TikTok or Huawei.

Tracing Meetings’ Transparency Shortfalls

Drawing on interviews with Brussels-based current and former MEPs, APAs, and EP observers, mandatory meeting disclosures remain unevenly enforced and many interactions still go unrecorded. As MEPs and APAs are responsible for self-reporting their meetings, they retain full discretion over how the purpose or content of these interactions is described. Given that the EP records do not offer more detailed information about the nature of the meetings, often vague or inaccurate descriptions add to the lack of transparency and limit public scrutiny. The analysis shows that examples of vague reasons include “various,” “general exchange of views,” “courtesy meeting,” “lobby meeting,” “meeting with TikTok,” and the like.

Notably, in meetings with Chinese companies such as those mentioned above, references to “China” in the stated purpose of the meeting are rare – unless the companies are registered under a trade or business association or as a non-governmental organization. Furthermore, identifying China-affiliated companies proves challenging. Several entities, including TikTok (Ireland), Volvo Cars (Sweden), and Shein (Singapore), register their headquarters in jurisdictions outside of China. This practice can obscure their country affiliations, particularly in the case of lesser-known companies, thereby undermining transparency and limiting insight into their connections with Chinese state or corporate structures.

Often, registered meetings do not state whether APAs or MEPs or both were part of the meeting – they merely indicate that the meeting was conducted on behalf of a MEP. This adds to the inaccuracy of the recorded data which hinders the EP’s efforts to improve transparency and accountability. During the research period, there were a limited number of meetings that were registered as APA-level meetings. Additionally, even when they are registered as such, they rarely provide the names of the APAs in attendance. Given that each MEP can employ multiple APAs, and that APAs can be working for many MEPs simultaneously, this presents a significant obstacle to transparency as well as to the EP’s ability to retrospectively trace the flow of information. For other meetings, it is not clear whether only the MEP attended or whether they were accompanied by their assistant(s).

Raising the Bar on Transparency

Transparency is not an end in itself. It is a prerequisite for democratic accountability – especially in a policymaking environment as dense as Brussels. When decisions with far-reaching consequences are shaped through continuous exchanges with stakeholders, citizens have a legitimate interest in knowing who has access to elected representatives and why. For the European Parliament, meeting disclosures are therefore more than a procedural obligation: they are part of the institution’s public mandate to explain how policy is informed, contested, and ultimately justified.

Strengthening that mandate will require making disclosure meaningful in practice. More consistent reporting, clearer minimum standards for describing the purpose of meetings, and unambiguous identification of who attended on the parliamentary side would significantly improve the informational value of the records, without discouraging legitimate consultation. As EU–China relations remain a long-term strategic challenge cutting across economic, technological, and security domains, the quality of transparency mechanisms will shape not only what the public can see, but also how confidently it can trust that the engagement in Brussels is being conducted under rules that are clear, enforceable, and fit for purpose.

Written by

Ivana Karásková

ivana_karaskovaIvana Karásková, Ph.D., is a Founder and Lead of CHOICE & China Projects Lead at the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in Prague, Czech Republic. She is a an ex-Fulbright scholar at Columbia University, NYC, a member of Hybrid CoE in Helsinki and European China Policy Fellow at MERICS in Berlin. She advised the Vice-President of the European Commission, Věra Jourová, on Defense of Democracy Package.

Association for International Affairs (AMO)

Association for International Affairs (AMO) is a Prague-based independent foreign policy think tank founded in 1997. Its main aim is to promote research and education in the field of international relations, and serve as a watchdog of the Czech foreign and security policies. AMO represents a unique and transparent platform where academics, business people, policy makers, diplomats, media, and NGOs can interact in an open and impartial environment.