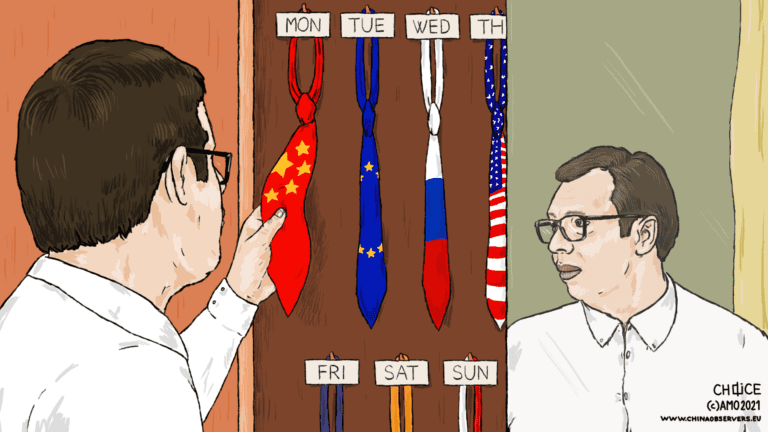

When Chinese and Serbian officials signed a free trade agreement (FTA) on the sidelines of the 2023 Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, it was hailed as the dawn of a new era in bilateral relations. The document was framed not just as an economic pact but as a symbol of deepening strategic alignment between Belgrade and Beijing. Although the deal officially came into effect in July 2024, it had already gained prominence during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s high-profile visit to Serbia in May of that year. Now, nearly a year into its implementation, new data is shedding light on how both nations are being affected by the agreement – and what the early returns reveal about this evolving partnership.

Even before the agreement officially took effect, economic ties between Serbia and China were deepening at a rapid pace. According to data from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, bilateral trade surged from $1.5 billion in 2014 to $6 billion by 2023. But behind this dramatic growth lies a more complex story – one marked by persistent imbalance. A decade ago, Serbia’s exports to China were negligible, totaling just $8.9 million in 2013, compared to $1.5 billion in imports from China. By 2023, Serbian exports had jumped to $1.23 billion – an impressive leap, yet still dwarfed by the $4.8 billion worth of Chinese goods entering the Serbian market.

This growing disparity has fueled concerns among economists and policymakers alike. Chief among them: that the free trade agreement could further widen the trade gap, exposing Serbia’s limited capacity to compete in China’s vast and competitive marketplace. Adding to the unease is the composition of Serbia’s exports, which raises questions about the sustainability – and strategic value – of its trade model with Beijing.

A Strategic Pact or a Symbolic Gesture?

A closer look at Serbia’s top exports to China reveals a troubling pattern. Of the five leading export categories in 2023, three consisted of raw or minimally processed natural resources. Copper ores and concentrates dominated the list, accounting for $842 million in exports, followed by refined copper at $301 million. The third most exported product – processed wood – trailed significantly at $26 million. While the overall export volume is substantial, critics argue that the composition of these exports tells a more complicated story.

At the heart of the debate is Serbia’s heavy reliance on copper – an industry now largely controlled by the Chinese mining giant Zijin, which operates locally through its two subsidiaries, Zijin Copper and Zijin Mining. This dynamic has fueled concerns about the exploitative nature of Serbia’s trade relationship with Beijing. As the free trade agreement begins to take effect, analysts warn it may further entrench China’s dominant role in sectors like mining, without creating meaningful opportunities for Serbia’s domestic, export-oriented industries to grow or diversify.

When the FTA came into force in mid-2024, officials in Belgrade heralded it as a landmark opportunity – a gateway for domestic companies to tap into the vast Chinese market. But by the end of 2024, the results were only partially beneficial for Serbia. The promise of access, it turns out, does not guarantee a competitive edge. Serbian exporters have faced this challenge before. The country’s earlier free trade deal with Russia failed to deliver a significant boost, largely because Serbian producers struggled to meet the scale and standards of demand.

History may be repeating itself. During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s May 2024 visit to Belgrade, both governments touted new export deals for Serbian dried plums and blueberries. Yet, so far, these gains remain elusive. Blueberries and dried plums, though negotiated directly, have yet to crack the top 50 Serbian exports to China. Meanwhile, raspberry exports, which are in the same category and were once seen as a success story, fell from $1.2 million in 2023 to just $832,000 in 2024. The data suggest a sobering conclusion: while the FTA opens doors, the real challenge lies in building the capacity to walk through them.

Another key promise tied to the FTA has yet to materialize. Officials in Belgrade pitched the agreement not only as a tool for boosting exports but also as a magnet for foreign companies – particularly those from countries lacking similar trade arrangements with Beijing. The idea was straightforward: by relocating production to Serbia, firms could capitalize on favorable terms to enter the Chinese market, turning Serbia into a strategic export hub. Yet, despite the ambition, reality has been far less clear-cut. Concrete results are hard to measure, and as of now, no public cases have emerged of companies relocating to Serbia to take advantage of the FTA. For all its theoretical appeal, this aspect of the agreement remains a promise more than a proven path.

Hopes with (a Lack of) Gains

In its first year of implementation, Serbia’s FTA with China delivered a notable uptick in bilateral commerce, but brought little change in the nature of the relationship. By the end of 2024, China had solidified its position as Serbia’s second-largest trading partner, trailing only Germany. The total trade volume between Belgrade and Beijing reached $7.4 billion, a significant leap from $6.1 billion in 2023. Exports from Serbia to China rose to $1.9 billion, representing just over six percent of Serbia’s total global exports. Meanwhile, imports from China climbed to $5.5 billion, accounting for 11.3 percent of total imports.

The $1.2 billion surge in total trade marked the sharpest single-year increase in more than a decade of steadily growing economic ties. Yet beneath the headline numbers lies a more nuanced picture. Serbia’s export portfolio to China remains overwhelmingly concentrated: 93 percent of all exports – roughly $1.76 billion – consisted of copper and copper-related products, the vast majority of which are tied to Chinese-owned mining operations within Serbia.

Opportunity with Caveats

As Serbia’s free trade agreement with China rounds out its first year, the early verdict is one of cautious pragmatism. Trade volumes have undeniably surged, signaling growing economic interdependence, yet the structure and direction of that growth underscore long-standing concerns. Rather than transforming Serbia into a diversified export hub, the FTA has so far deepened existing asymmetries – cementing China’s dominance in key sectors like mining while exposing the vulnerabilities of Serbia’s narrow export base.

Still, it is premature to render a final judgment. The deal remains an opportunity, particularly if Belgrade can leverage it to attract investment, encourage value-added production, and expand beyond raw materials. But such outcomes will require strategic planning, stronger institutional support for exporters, and a more deliberate push for diversification. For now, the agreement stands as a reminder that while access may be granted overnight, competitiveness is built over time – and the window to shape that trajectory is already narrowing.

Written by

Stefan Vladisavljev

vladisavljev_sStefan Vladisavljev is CHOICE Visiting Fellow. He is also the Program Coordinator of the Serbia-based non-governmental organization Foundation BFPE for a Responsible Society. He analyzes Chinese presence in Central and Eastern Europe with a special focus on Serbia and the Western Balkans.