While German diplomacy and businesses increasingly set their eyes on Southeast Asia, the allure of the Chinese market remains strong.

Berlin Dragging Its Feet on De-Risking

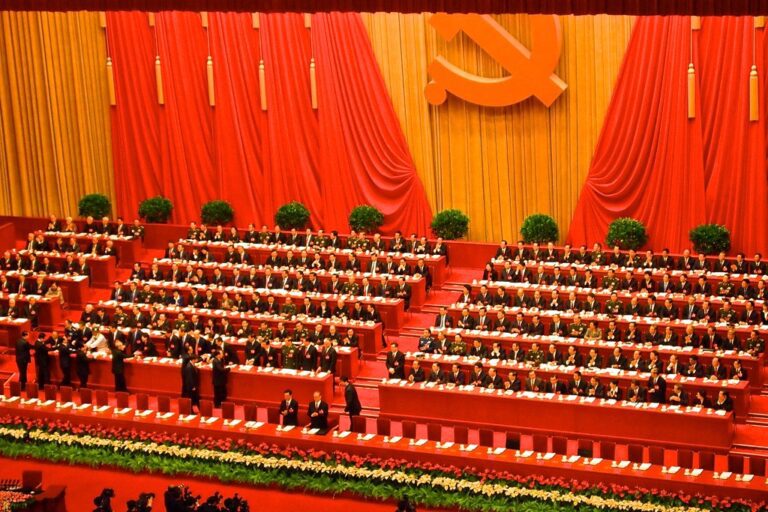

As German Chancellor Olaf Scholz embarked on his second visit to China in April 2024, accompanied by a high-level business delegation, the trip underscored the delicate balancing act Germany must perform in its relationship with Beijing. The journey, set against the backdrop of the European Union’s rising concerns over economic dependency and unfair competition, highlighted Berlin’s strategic conundrum: How to reduce reliance on China while maintaining robust trade ties?

This visit, Scholz’s second as chancellor, aligns with Germany’s newly articulated “Strategy on China,” which aims to reduce dependency on the Chinese market while preserving robust economic ties. The endeavor to “de-risk” is fraught with challenges, reflecting the broader strategic dilemma of maintaining economic stability while addressing geopolitical tensions. This is further complicated by domestic opposition in Germany to de-risking from China. However, this strategy is crucial for Germany and the West’s geoeconomic positioning.

The German economic foreign policy has historically taken a different stance from that of other players, especially the United States. While the US regulates both foreign investments within its borders and US investments abroad to mitigate exploitation risks, Berlin focuses solely on regulating foreign investments within its territory. This policy enabled German enterprises to heavily invest in China even when first steps of de-risking and decoupling were already all the rage in the late 2010s. Since 2000, Germany’s economic ties with China have evolved dramatically, culminating in a trade volume that reached €253.1 billion in 2023. That year also marked the eighth consecutive year of China leading the list of Germany’s most significant trading partners.

Recently, Germany’s economic entanglement with China has seen both a deepening and a reevaluation amidst shifting global trends, such as the COVID-19-pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The tides are subtly changing. For instance, German investment into China faltered by about 30 percent in the first three quarters of 2023. Thus, 2023 marked the first time German FDI in China shrank significantly, signaling a cautious reassessment of risks and opportunities by German companies. This recalibration is driven by the unpredictability of geopolitical tensions which threaten supply chains, prompting German businesses to adapt strategies to deal with the China risk in their corporate portfolios.

For instance, the German automotive industry relies heavily on China for its magnesium supply, a critical component in car manufacturing. German companies have previously encountered temporary disruptions in magnesium availability, raising concerns about their ability to handle long-term supply chain instability.

Given these circumstances, one might assume that the entire German economy is actively de-risking by diversifying its supply chains and reducing its dependency on China for sourcing, manufacturing, and sales. However, the reality is more complex.

Major German corporations continue to make significant investments in China. A prominent example is the German chemical company BASF, which is constructing a large-scale chemical complex in Zhanjiang, with planned investments amounting to €10 billion, aiming to be fully operational by 2030. Other German enterprises like VW, Siemens, or Hella are hesitant to move investments and production outside of China as part of de-risking, opting for localization strategies instead.

Scholz’s visit to China, marked by the presence of top German business leaders and discussions on market access and trade, also suggests that Germany is not fully committed to de-risking. Despite commitments to the contrary, the trip signaled that Berlin is sticking to the old strategy of prioritizing economic ties over broader geopolitical concerns raised by other European leaders.

At the same time, however, concerns over unequal treatment, local protectionism, and regulatory uncertainties persist among German companies operating in China. These fears recently intensified with the German government’s strategic shift to reduce investment guarantees for companies investing in China. Berlin has reduced the volume of investment guarantees for companies investing in China, from 745.9 million euros in 2022 to just 71 million euros in 2023.

Southeast Asian Fix?

An increasingly uncertain investment environment inside China as well as geopolitical tensions continue to reshape the global economic landscape. Thus, 60 percent of German businesses operating in China have already taken measures to improve supply chain reliability, and about 40 percent plan further steps by the end of the next year due to rising geopolitical tensions. For many of them, Southeast Asia emerges as an increasingly alluring destination.

The allure of Southeast Asia for German companies is underscored by ventures like Porsche AG’s exploration of assembly operations in Malaysia as well as Thailand’s potential emergence as Germany’s electric vehicle manufacturing hub in Asia. Additionally, Vietnam has become a focal point for German business interests, too.

Geopolitical tensions serve as a primary engine for these adjustments by German businesses currently operating in China who seek to reduce business risks. Brands like Mercedes-Benz, BMW, and Adidas enjoy widespread recognition in the region. Moreover, German firms’ emphasis on ethical operations and contributions to local education and training have elevated their standing.

The increasing prowess of Chinese companies in innovation is another factor reshaping the economic landscape for many German firms operating in China. China has advanced its domestic capabilities in research and development, accompanied by rising labor costs, thus making the market increasingly competitive. In contrast, Southeast Asian nations like Vietnam and Cambodia offer more attractive conditions with lower labor costs and less formidable domestic competition, prompting German corporations to consider relocating their operations to these regions.

This shift is also reflected in the German government actively pursuing new economic partnerships in Southeast Asia – a part of a diversification strategy developed to lessen reliance on China. The new approach as exemplified by German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock’s visit to Malaysia in January 2024. As part of her six-day diplomatic tour covering the Middle East and Southeast Asia, Baerbock’s primary agenda was to strengthen ties with Kuala Lumpur. German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier previously visited Cambodia in 2022, followed by Thailand and Vietnam in 2024. In 2022, Scholz attended the G20 summit in Indonesia and engaged in bilateral meetings in 2024. Such visits by high-ranking German officials highlight Berlin’s strategic interest in enhancing economic relations with Southeast Asia.

The region, which navigates the great power rivalry between China and the US while striving to preserve its own agency, presents a complex environment for Germany and the EU, joining a cast of players including Japan. The German government’s outlook on ASEAN countries as “partners” underscores a departure from its approach prioritizing engagement with China. The German strategy aligns with ASEAN nations’ aspirations to diversify their economic portfolios amidst the backdrop of Sino-US rivalry while striving to preserve its own agency.

Despite this appeal of Southeast Asia for Germany, challenges also persist. Chinese manufacturing prowess in the region remains unparalleled. Relocating production entails significant costs and inefficiencies for German business, exacerbated by Southeast Asian suppliers’ reliance on Chinese imports for raw materials and semi-finished products. Moreover, ASEAN continues to struggle with regional economic integration, which greatly diminishes its potential for developing regional production networks.

Meanwhile, China continues to offer significant advantages as a manufacturing location. Despite rising labor costs, trade disputes and the need to diversify supply chains, the country remains an indispensable part of the global supply chain due to its extensive production capacity, experienced suppliers, mature infrastructure and large domestic market.

China’s vast consumer market remains key for both Germany and many ASEAN countries alike. Despite the draw of lower labor costs, Southeast Asia cannot replace China as a sourcing base due to logistical complexities and the interdependence between ASEAN and China’s economy.

While Southeast Asia offers promising opportunities, it is no replacement for China across the board. Despite significant investments in the region, many German businesses continue to find China’s consumer market indispensable. This dual approach underscores Germany’s need to balance economic interests with geopolitical realities: While the pivot to Southeast Asia is crucial, many economic roads for Germany inevitably still lead to China.

Written by

Tim Hildebrandt

Tim Hildebrandt is a Ph.D. candidate in political science and economics at the University of Duisburg-Essen and a Research Associate at the Ruhr West University of Applied Sciences. His research focuses on the intersection of politics, economics, and geography.

Julian Klose

Julian Klose is an editor and freelance journalist based in Heidelberg, Germany. In addition, he is a regular contributor to several foreign policy think tanks and conflict research institutes. His areas of interest include security policy, trends and developments in East Asia, and Germany's relations with China and Korea.