Does the European Green Deal Really Rely on China?

This article is part of a series of articles authored by young, aspiring China scholars under the Future CHOICE initiative.

Still dealing with the heavy blow dealt by the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU has sought to shore up its weakened economies and reshape its market with a view of the future.

As such, the EU has adopted the Next Generation EU recovery plan, which aims to make Europe greener, more digital, and ultimately more resilient to external shocks. The centerpiece of this plan is the European Green Deal, which sets carbon-neutrality by 2050 as its main goal. The policy is era-defining not only due to the ambitious mission to become the first climate-neutral continent, but also in its aim for the transformation of the industrial structure of the entire EU.

At present, the transport sector makes up around 25 percent of Europe’s total gas emissions and road transportation is responsible for almost 72 percent of the gas emissions. Cumulatively, the two segments account for about 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions across the whole EU. However, the automotive industry that drives the emissions in these segments also represents about seven percent of total EU GDP and provides direct and indirect jobs to 13.8 million Europeans. Given the European Commission’s stated goal of a 90 percent reduction in transport-related greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, the goal of a climate-neutral European community is likely to come at a heavy societal cost.

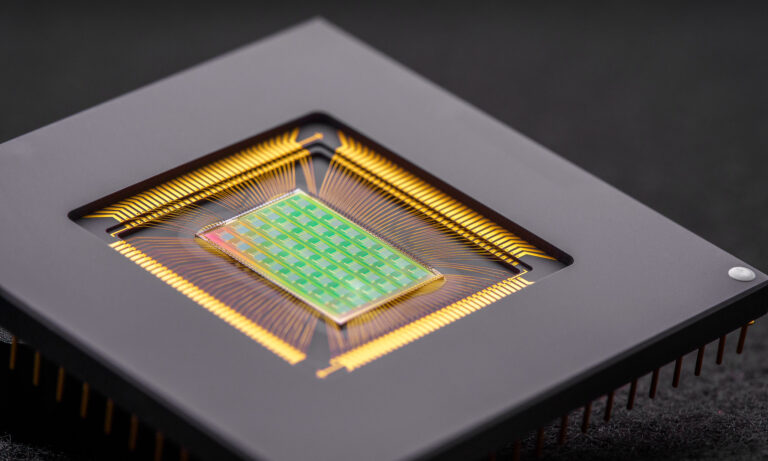

A balanced plan to maintain employment and industrial capacity while pursuing green policies therefore calls for radical changes in the automobile industry. Namely, it necessitates a rapid shift to Electric Vehicles (EVs) and away from internal combustion engines. However, this transition is not ensured to be seamless. In fact, EVs, especially the next-generation EVs, require advanced digital technologies, including 5G networks and a stable supply of critical raw materials (CRMs) for batteries and other auto parts common in these modern vehicles.

Due to the confluence of these circumstances, the EU’s path towards fulfilling the commitments set by the Green Deal may encounter obstacles built by the crucial supplier of these technologies: China.

EV Shift Adds Risks

Of course, the shift towards EVs includes many moving parts aside from the geopolitical premises.

Just recently, the European Commission presented a Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy with lofty goals such as 30 million zero-emission cars in operation by 2030. To achieve these goals, automobile companies actively invest in digital technologies based on CASE (Connected, Autonomous, Shared, Electric). The emerging EVs are supposed to be constantly connected to the internet bidirectionally via 5G networks which also means generating a huge amount of private data on passengers including their location, traffic conditions, conversation records, performance of car components, etc.

Chinese tech giants also enter EV markets through information technologies (ICT). Allowing Chinese firms to implant their ICT to EVs involves a risk that the companies bound by Chinese law and under the regulations of the government, can access and collect sensitive data. As Norway (an EEA member) is fast becoming a major export market for Chinese start-ups, a launching point into the EU single market is already opening.

The growing popularity of EVs and renewable energy also increase the demand for CRMs. China has a predominant share of CRMs import to the EU , for instance, pure magnesium (94 percent), whose main end-user is the transport sector, natural graphite (66 percent) used in lithium-ion batteries for EVs, and rare earths (40 percent). To meet the future energy demand through renewables, the power sector will face a massive deployment of wind and solar photovoltaic technologies, whose major producer is, again, China.

Shifting to the Chinese domestic market, it is unclear to what extent the EVs market keeps open for foreign companies In 2018, it was announced that foreign ownership limits on automakers would be phased out by 2022. Nonetheless, existing market entry and project investment requirements and administrative rules remain in place. As a result, setting up joint ventures with local entities will probably remain the easiest option for foreign companies, leading to the sensitive cases of technology transfer.

In the background, China`s intention to transform itself into a global technology powerhouse as put forward by the Made in China 2025 (MIC25) program lingers. One of the specific goals in MIC 25 addressed the need to increase the domestic market share of Chinese suppliers – for “basic core components and important basic materials” to 70 percent. A supplementary semi-official document Made in China 2025 Key Area Technology Roadmap proposed specific targets for the market share of home-grown technologies.

Similarly, new energy vehicles and new and renewable energy equipment are listed. This de facto means excluding imported goods or foreign companies from the market, which infringes upon the rule of non-discrimination of the WTO. In a nutshell, the Technology Roadmap accentuates Beijing’s ambitions to expand domestic production and build up home-grown brands.

In response to international concerns, MIC25 has later disappeared from the official rhetoric. Yet, sector-specific goals largely remain the same, as do the overall strategic objectives of Chinese industrial policy. Notably, these intentions come at the expense of other countries; namely Germany, whose automobile industry heavily invests in China, especially in the EV market. On the whole the European automotive industry is considerably dependent on the Chinese market. In 2019, China became the second main destination for EU-produced passenger cars and one in three German cars is currently sold in China.

Diversifying Suppliers

As hinted above, there are numerous concerns surrounding the EU shift towards EVs. In order to mitigate these obstacles, the EU ought to consider curtailing its dependency on China.

In July 2020, the Commission report on 5G security pointed out the urgent necessity to mitigate the risk of dependence on high-risk suppliers, challenges in designing and imposing appropriate multi-vendor strategies for individual mobile network carriers or at a national level due to technical or operational difficulties. The report further emphasized the need to introduce a national FDI screening mechanism without delay. Despite the fact that the report does not refer to China as such, the document mentions concerns and risks that clearly relate to technological cooperation with China.

In fact, one of the most evident options to tackle the aforementioned concerns would be the exclusion of Chinese companies from the 5G network markets. Nevertheless, relying solely on European companies, such as Nokia or Ericsson, may prove to be insufficient.

This situation may be surmounted by cooperation with other partners. After Brexit, the UK and Japan have already concluded the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), including digital sectors with data protection at GDPR levels, allowing Japanese firms to serve as a possible alternative to Chinese tech champions. The EU and Japan have also concluded the EPA, but the digital sector was left out of the agreement. Consequently, negotiations concerning the EU-Japan 5G cooperation need to accelerate so that European tech companies have a broader list of suppliers available.

The Chinese supply risk applies to CRMs as well. In 2010, China abruptly cut off all rare earth exports to Japan due to a dispute near Japan’s Senkaku Islands. China now threatens the US alike, exploring the impacts of these export restrictions on companies in the US and Europe. Brussels is aware of the risk as evident in the European Commission document on CRMs that defines access to resources as a strategic security question for Europe’s ambition to deliver the Green Deal.

In the short-term outlook, other third countries, like Kazakhstan or Mongolia, represent a realistic solution to supply diversification, but it is also crucial to enhance the EU’s supply capacities in the long-term. For instance, Poland or Portugal have deposits of cobalt and lithium, which are essential components for lithium-ion EV batteries. Besides the risk reduction, mining of those CRMs in Europe could create new job opportunities for those who may lose their jobs owing to de-carbonization. On the other hand, as the case of the most promising region in terms of lithium mining in Portugal shows, the local concerns about environmental impacts may inhibit the development.

As an alternative, mining rare earth in the Pacific Ocean would hardly cause this “Not in my backyard” problem. For example, France has a deposit in the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ), east of Tahiti in French Polynesia. Rare earth deposits can also be found in Japan’s EEZ. Though it is yet in a phase of research and assessment and far from commercialization, the cooperation for mining and lifting technology development is feasible.

Considering ‘China Risk’ in Business

After China’s rare earth embargo a decade ago, Japan recognized “China risk” not only for stable CRM supply, but in the business environment in general. The notice given to Japan was solidified as the Chinese population chose to boycott Japanese products over political disputes as well. Though Japan does not represent a unique case.

American EV manufacturer Tesla may now struggle with a similar situation based on customer complaints, negative media coverage, and tightening control by the authorities on both sides of the Pacific. Considering the inherent risks of the Chinese market and the ambition of MIC25, it is difficult to predict to what extent the Chinese business environment will remain attractive and profitable for foreign companies. Meanwhile, a trade war could tamp down its domestic US business.

Hence, diversification in alternative emerging Asian economies is necessary to mitigate the risk. ASEAN countries show promising signs of future EV market growth and development. The region’s annual new investment in passenger electric vehicles will grow to $6 billion by 2030, while Taiwan is already a leader in numerous technological industries. India likewise has become a key diversification opportunity, especially in EVs. In May, the EU and India concluded a connectivity partnership to support private investments in high-standard physical infrastructure including transport and energy sectors.

Still, China is likely to nonetheless remain an attractive market for European firms, especially after a rapid recovery in the Chinese economy after the pandemic. Yet counting on the omnipresent and inevitable interaction with China is not a wise plan. Aside from the well-known political dilemmas, China’s increasing authoritarian control of important national industries could well undermine the remaining advocates found among major EU business leaders.

In terms of green policy and the shift to greener technology like EVs, less dependence on China is a key to saving the EU from facing down the stark contrast between achieving economic growth targets under adherence to the Green Deal and the vaunted existence and promotion of a “Community of Values.”

The opinions expressed by the author are his own views, not those of Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Written by

Naoyuki Ito

Ito Naoyuki is an attaché of Embassy of Japan in the Czech Republic, serving in this capacity since 2019. Previously, he served in the Intelligence and Analysis Service as well as the OECD division of the Economic Affairs Bureau within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.