This article is part of a series of articles authored by young, aspiring China scholars under the Future CHOICE initiative.

Global crises have exposed the fragility of today’s just-in-time economy. Pandemics, climate shocks, and wars have repeatedly disrupted centralized supply chains, revealing vulnerabilities that adversaries can exploit. Trade links themselves have become geostrategic weapons: tariffs, embargoes, and export controls are now common instruments of coercion.

A striking example is rare earth metals. In 2023, China supplied nearly all of the EU’s rare earth imports, leaving Europe vulnerable to supply chain pressure. By 2025, Brussels began actively reducing its dependence not only on Chinese rare earths but also on imported chemicals, medicines, and other essential goods. In short, both China and the EU now see economic resilience – built on autonomy and diversification – as a strategic imperative. One promising approach is biomimetic geoeconomics: deliberately structuring energy, material, and food systems to mimic the patterns nature has refined over billions of years to withstand shocks.

Nature as Mentor

Biomimicry starts from a simple premise: nature has already solved many resilience problems. Since Janine Benyus’s pioneering work in 1998, researchers have distilled a set of “life’s principles” found in every thriving ecosystem. Out of the nine life’s principles, the ones most relevant in this context are:

- Run on sunlight – natural systems rely on renewable flows, not stored fuels.

- Recycle everything – one organism’s waste becomes another’s resource.

- Reward cooperation – mutualism and symbiosis strengthen the whole ecosystem.

- Bank on diversity – variety creates resilience and buffers shocks.

- Curb excesses from within – self-correcting mechanisms prevent overuse and collapse.

If human economies could replicate these principles – by using renewable flows, designing for reuse, encouraging diversity and cooperation, and embedding feedback – they would become more shock-resistant, both economically and socially. In short, nature offers a powerful blueprint for resilient design.

Toward Biomimetic Economies

To put these principles into practice, economies must reconfigure their three main pillars – energy, materials, and food – to function more like ecosystems. Both China and the EU are already taking steps in this direction. Recent policies in each region reflect nature’s logic: decentralized energy production, closed-loop material flows, and regenerative agriculture.

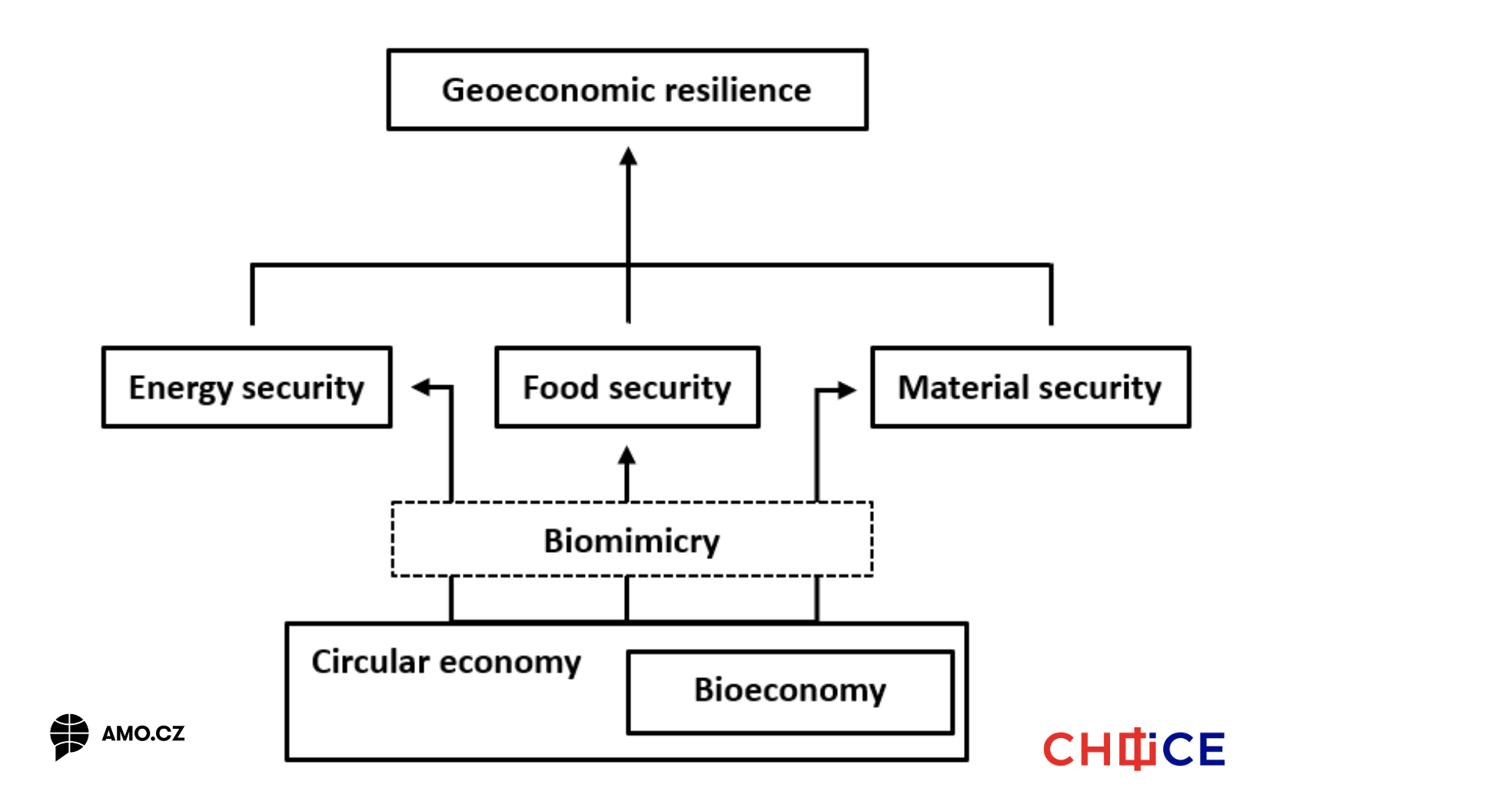

Enhancing geo-economic resilience by circular economy and bioeconomy based on biomimicry. Source: compiled by the author.

1. Energy: Running on Sunlight

Echoing the nature’s reliance on renewable flows, China and Europe are rapidly replacing imported fuels with domestic green power. China now hosts the world’s largest and fastest-growing renewable energy system. By mid-2025, it has installed 2.09 billion kW of renewables – roughly double the 2016-2020 total. About one third of its electricity now comes from green sources. This clearly reflects Beijing’s goal of securing a homegrown energy base to guard against possible supply disruptions.

Europe made a similar pivot after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The REPowerEU plan accelerated the rollout of renewables and efficiency measures, with renewables now accounting for 47 percent of the bloc’s electricity. In the first half of 2024, wind and solar generated 30 percent – surpassing fossil fuels – and by late 2024, solar power alone overtook coal generation. Gas demand has fallen 17 percent since 2022, thanks to better insulation, wider use of heat pumps, and behavioral changes.

By tapping abundant clean energy and conserving it, both economies are beginning to run on sunlight and wind, just like nature. Whereas China’s push for renewables is both climate-driven and strategic, in Europe, wind turbines and solar farms – once marginal – now form the backbone of the grid. The EU’s 2023 energy strategy targets 42.5-45 percent renewables by 2030. Together, these changes are creating distributed, domestic energy networks, which are better able to absorb shocks and reduce dependence on distant fuel sources. If one country’s gas supply is cut, solar and wind from neighbors can help fill the gap.

2. Materials: Closing Loops, Securing Supplies

In nature, nothing goes wasted. Both Brussels and Beijing are now trying to replicate this circularity by recycling more and diversifying supplies. The EU treats dependence in critical materials as a major security risk. The 2023 Critical Raw Materials Act mandates that by 2030 at least 10 percent of strategic metals must be mined, 40 percent processed, and 25 percent recycled within the EU, with no more than 65 percent of any material coming from a single foreign source. These rules “bank on diversity” by promoting new mines and recycling, and capping dependence on one supplier.

Currently, China supplies 98 percent of the EU’s rare-earth imports. To change this, the EU is stockpiling, forging new trade partnerships, funding recycling research, and redesigning products. The Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation and Right-to-Repair law (both in force since July 2024) require goods to be more durable and easier to repair. An upcoming Packaging Waste Regulation (2025) and updated eco-labels will further encourage reuse over disposal. These policies push firms to design in loops – much like ecosystems, where one organism’s waste nourishes another.

China is also closing its own material loops under its “ecological civilization” concept. The 14th five-year plan has made a national recycling system a core goal. By 2024, China aims to raise resource productivity by 20 percent (compared to 2020), and annually recycle 60 million tons of paper, 320 million tons of scrap steel, and 20 million tons of non-ferrous metals. Policies incentivize industrial symbiosis: eco-parks connect factories so that one factory’s waste becomes another’s input, and farmers are encouraged to return crop residues to fields instead of burning them. Beijing is also investing in second-hand markets, vehicle remanufacturing, and overseas mining (especially in Africa and Latin America) while maintaining strategic metal stockpiles. These steps mirror nature’s strategies for spreading risks and building redundancy.

3. Food: Regenerating the Base

Food and farming are inherently tied to natural cycles, but both China and the EU are enhancing resilience through agriculture. The EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy (2020) and updated Common Agricultural Policy set ambitious 2030 targets: cutting the use of chemical pesticides by 50 percent, halving fertilizer losses (while maintaining yields), dedicating 25 percent of farmland to organic farming, and reserving 10 percent of arable land for ecological focus areas. These steps help “curb excesses” of agrochemicals and restore healthy soils. The EU also promotes diverse crop rotations, pollinator habitats, and nutrient recycling, and aims to cut food waste by 50 percent. Together, these measures will help buffer Europe’s food supply from climate and geopolitical shocks by making it greener, more diverse, and more cyclical.

China also prioritizes food security, given its 20 percent share of the world’s population lives on just 9 percent of global cropland. Historically, Beijing’s solution was near-total self-sufficiency. But decades of intensive farming have degraded about 40 percent of China’s arable land through erosion, salinity, and pollution, and contaminated 20 percent with heavy metals. Overuse of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides has fueled this decline, making agriculture the single largest source of China’s water pollution.

In response, Beijing is shifting toward sustainability. The 2024 “No. 1 Document” on agriculture focuses on restoring soil quality, converting farmland into high-standard fields, and boosting organic matter. Fertilizer subsidies are being reformed and farmers are encouraged (through payments and training) to adopt low-input, regenerative methods. These include no-till farming, crop rotations, and integrated crop-livestock systems that rebuild soil carbon. Hundreds of demonstration farms now showcase these sustainable practices.

Mimicking Billion-Year Wisdom

From energy grids to mines to farms, the EU and China are quietly converging on nature-inspired policies. They recognize that in the age of constant shocks, the most resilient systems are those designed by nature: diverse, locally adapted, and self-regulating diverse agents.

The transition is still in its early stages. Decades of fossil dependence and linear consumption will not vanish overnight. But the direction is clear: both economies are starting to “fit form to function” on a grand scale by rebuilding infrastructure to run on renewable flows, turning waste streams into resources, and rewarding cooperation with the environment. A biomimetic economy would not only be low-carbon and circular but also far less vulnerable to weaponized trade. In the end, the greatest strategic advantage may go to those who best mimic life’s genius.

Written by

Alex Tóth

Alex Tóth was a Blue Book trainee at the European Commission (CINEA) in 2024. He holds an MSc in International Political Economy from NTU Singapore. His research focuses on how biomimetic principles, as manifested in circular and bioeconomies, can enhance energy, material, and food resilience in the age of geoeconomics.