The 2022 Winter Olympic Games in Beijing are set to kick off with pomp and circumstance later this week. Ahead of this program, professed to be apolitical, there is no shortage of controversy.

While the International Olympic Committee and Chinese media continuously appeal not to mix sports with politics, the political ramifications of the global sports event appear even more overwhelming than they were during the summer of 2008.

Why then, is the concept of “political neutrality” not applicable to the games in Beijing?

This answer is rather self-evident. The “organizing a global sports event” is to serve as an implicit showcase and promotion of a Chinese systemic advantage over the West.

Chinese Comeback to the Global Stage

The Winter Games this year are not the first Olympics in China, but they are nonetheless unique due to shifts in the international and domestic situation since 2008.

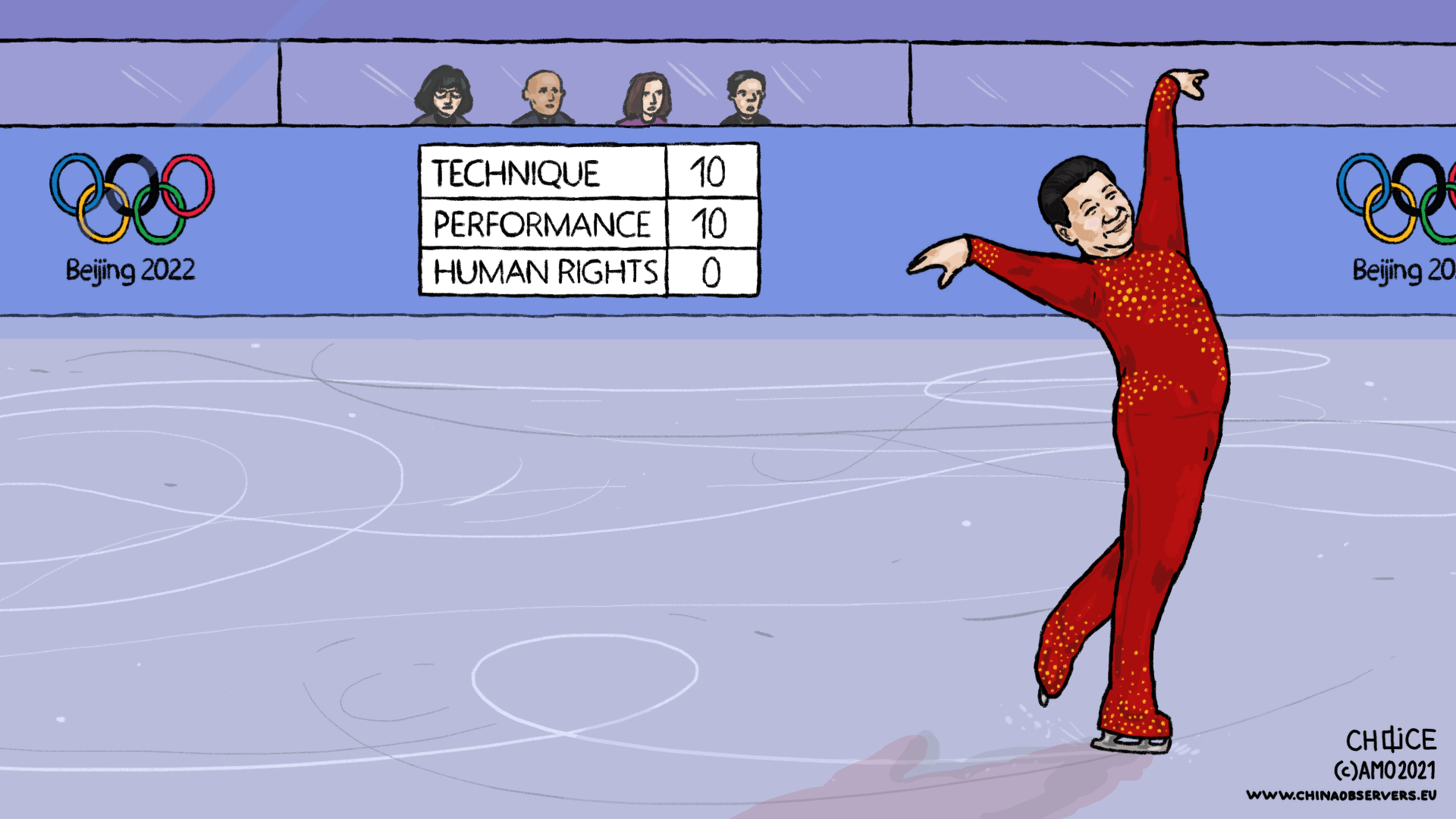

The Summer Olympics in Beijing that year were a symbolic realization of China’s re-entry into the global arena, with a clearly defined narrative aimed at promoting a positive general reputation for the country and highlighting its accomplishments. A large part of the international messaging was also aimed at providing the international community with a positive presentation of China. These rosy images were then utilized as further justification for economic and political engagement, despite controversies concerning lack of economic reciprocity, human rights, and more.

The process, however, had its setbacks.

The first Chinese application in 1993 to organize the Olympics was turned down by the members of the International Olympic Committee. When China finally won the bid in 2001, it was also a clear sign of the efficiency of China’s diplomatic apparatus which managed to overcome the international aftershocks of the 1989 crackdown. Now, after decades of economic reforms, China was finally awarded an opportunity to showcase these achievements to the global public.

The political objectives were, together with the soft power effect of winning the medal classification over the US, to create the positive narrative of the government’s management skills, ability to build modern infrastructure, master the logistics challenges and generally present China globally as a fast-developing country with far-reaching aspirations.

These narrative goals were, however, imposed with ordinary instruments of the Chinese authoritarian apparatus. Chinese authorities have restricted the foreign correspondents’ abilities to travel, curbed access to ordinary citizens, and issued special instructions on behavior for the population, seeking to show a proper and ‘civilized’ image of Chinese people to the world. Additionally, the government relocated and detained several NGO workers and human rights activists.

Despite the strong-arm tactics, the desired result was achieved – the 2008 Summer Olympics successfully enhanced the image of a trustworthy and responsible China. This happened despite Beijing’s violations of human rights, especially the use of excessive force by Chinese authorities during the riots in Tibet in March 2008.

The Efficiency of People’s Democracy

China is undoubtedly a very different nation today.

Its economic position is stronger, ideology more intense, and diplomatic aggressiveness is at a fever pitch. It is actively using its resources to coerce other countries such as Lithuania, promotes non-democratic global order together with, or at least parallel to, Russia, and breaks both commitments and international law in Hong Kong, the South China Sea, Xinjiang, and elsewhere. In a most striking example of China flouting international commitments and the basic respect for human rights, Beijing has designed and organized systemic persecution of Uyghurs due to their ethnicity and religion, employing technological advances and anti-terrorism propaganda to create a new-era police state.

In 2022 the support for political and economic engagement with China is limited, with a rather skeptical and negative view on Chinese policies in many of the Western countries. But the 2022 Olympics are no longer about the world’s acceptance as it was 14 years ago. Now the goal is instead to showcase China’s superiorities over “Western democracies” and legitimize the policies with “Chinese characteristics.”

The 2022 Winter Olympics, in contrast to 2008, will symbolize an end of an era.

The games come at the culmination of CPC’s 100 anniversary and Xi Jinping’s second term in power. Successful management under difficult pandemic circumstances will work as an example of an effective political system, fitting firmly within the rhetoric of China’s “people’s democracy” often promoted in recent disputes with the US.

The events on the sidelines of the games between Chinese and foreign leaders are designed to become an important arena for the promotion of a “community of shared future for mankind” – Xi Jinping’s slogan reflected also in the official Olympics motto, “Together for a Shared Future.”

As much as the concept sounds positive, it reflects China’s “new paradigms” of human rights concepts and international community structure that are contrary to the current liberal international order.

Under this concept, the foreign leaders’ attendance projects support for cooperation with China to both local and international audiences. Internally, the Party will seek to keep the Party apparatus united, mobilize and stabilize the society, and promote the concept of “two establishments”.

The decision not to attend the Games by several countries’ officials, explained either as diplomatic boycott or pandemic cautiousness, has garnered attention but the number of these countries has remained limited. China has censored the information on the boycott internally and the Foreign Ministry dismissed the boycott campaign as irrelevant.

Some of the countries that confirmed their attendance (Russia, Pakistan, Kazakhstan) share China’s view on the world and its objectives. Others, mostly Europeans, who did not exclude the possibility to attend the games in an official capacity (like Poland or Germany) will be showcased by the propaganda as promising examples of positive cooperation.

Olympic Bubble

Finally, the Games are held under the pandemic, which makes the event even more significant – not only in terms of public health. The pandemic bubble also perfectly helps to control the distribution of the narrative of China’s systemic advantage.

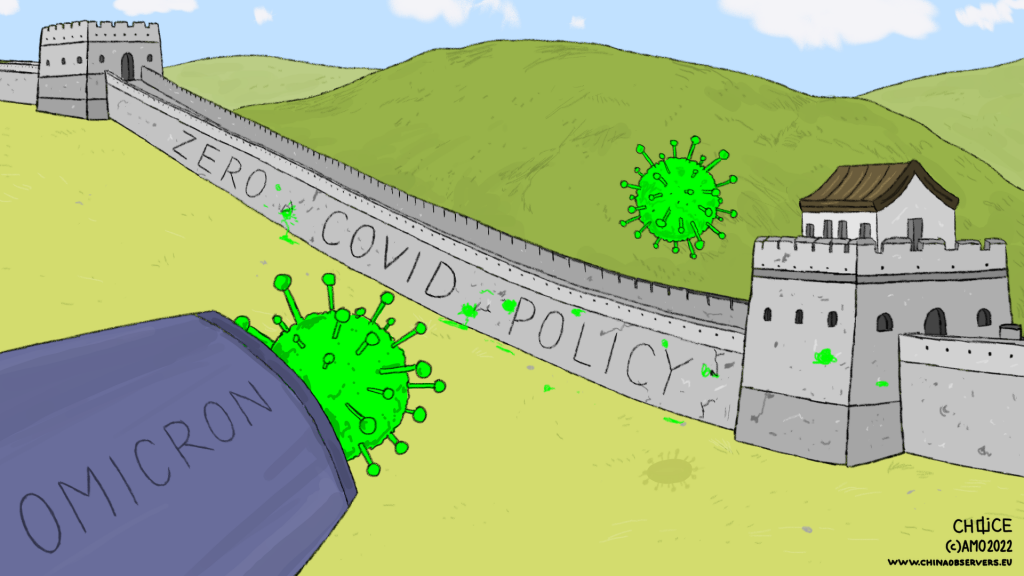

Only one year after Tokyo, Beijing (and Zhangjiakou) are seeking to organize a world-class sports event with as few as possible coronavirus infections among the participants on the spot, but also the general population. At the same time, omicron finds its way into China, infections rise, including in Beijing and the “Olympic bubble”, as well as several cities put under strict quarantine, with massive testing and lockdowns under China’s “zero-COVID” policy.

These radical measures are in place due to the low efficiency of Chinese vaccines, poor condition of China’s health care system, and political requirements of social control and stability. Obligation to vaccinate, pre-entry and daily tests, and complete separation of athletes’ delegations, journalists, and officials from the ordinary Chinese are designed to prevent an outbreak.

There will be no foreign visitors of course, but also no tickets sales for the public, just pre-invited guests as spectators selected by the authorities. The logic of organizing a similar sports event under the global pandemic is, in the end, quite questionable, just as it was last year in Tokyo, where no spectators were allowed at all.

While the pandemic precautions explain most of the security measures, the ever-present surveillance is also reflective of the logic of functioning of China’s authoritarian system. Keeping the risks of surveillance in mind, including the revelations about the security holes in the official Olympics app, Danish, Netherlands, and UK officials advised their team members not to bring electronic devices to China.

In any case, there will simply be no escaping politics at the upcoming 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

Written by

Marcin Przychodniak

Molos123Marcin Przychodniak is an Analyst at Asia-Pacific program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), focusing on Chinese politics and a former diplomat in Beijing.