As Czechs Head to the Polls, China Remains on the Margins

This article is part of an exclusive new series from CHOICE focusing on China as a topic in elections across Central and Eastern Europe.

As Czechs hand in their ballots today and tomorrow, they will be deciding on the future of the country. This includes the direction of its foreign policy.

Curiously enough, this election seems to be distinctively different when it comes to focus on foreign policy issues in general and on China in particular from the previous both general and presidential elections, held in 2017 and 2018 respectively.

In both instances, China featured heavily in the political debates, in which none of the parties or individual politicians felt they could afford to ditch the topic altogether. This time, however, China as a political issue has faded away and almost disappeared.

The lack of interest in China may be surprising, given the plethora of China-related topics occupying the Czech media and policy circles in the Czech Republic during the past four years.

Charting China’s Rise to Public Consciousness

Starting in 2018, Chinese company CEFC, which posed as the herald of Chinese investment to Europe and established its headquarters in Prague, was rumored to be near bankruptcy. Later, its operations were revealed to be essentially a Ponzi scheme fueled by local financing. CEFC was bailed out by the Chinese state-owned CITIC company which came to the rescue and acquired its assets in a final bid to save face. Ye Jianming, the chairman of CEFC and a special advisor on China to the Czech President Miloš Zeman, disappeared in China on a corruption probe.

A year later, another China-connected scandal broke in Czech media when the investigative journalists uncovered evidence of a troubling Chinese influence in Czech academia.

In late 2019, Czech Senate President Jaroslav Kubera was planning a visit to Taiwan as the head of a delegation scheduled for February 2020. When he suddenly passed away in January 2020, the plans for the visit were halted. However, Czech media revealed that, shortly before his death, Kubera received a harshly-worded letter from the Chinese Embassy in Prague. The message specifically threatened repercussions for Czech companies if he proceeded with his plans to visit Taiwan. Strangely, the letter was handed to Kubera through the Office of the Czech President, raising questions as to how much the president’s advisors are complicit in threatening Kubera, the second-highest ranking constitutional figure in the Czech political system.

Nevertheless, Kubera’s successor Miloš Vystrčil proceeded with the visit to Taiwan despite similar threats. For example, it provoked harsh comments from Wang Yi, the Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs, who ranted that Vystrčil will “pay a heavy price” for leading the delegation to the self-governing island.

The threats against Vystrčil, which Wang made during his visit to Berlin, were not taken lightly by the Europeans. Instead of stopping the delegation in its tracks as he may have planned, Wang’s comments provoked support for the trip to Taiwan. The outpouring of support even included a joint letter signed by several members of the European and national parliaments, and verbal condemnation by representatives of European Commission, Germany, France and others.

Still, the list of Czech-Chinese controversies over the past four years would not be complete without mentioning the outbreak of the coronavirus epidemic, which placed China on the map of even those Czech voters who deliberately avoid foreign policy issues.

To summarize the years-long saga of worsening Czech-China relations; the experience with CEFC and the lack of Chinese successful investment added to the already rising disillusionment on the side of some Czech politicians, including President Miloš Zeman, who originally advocated the most for the economic and political cooperation with China. Scandals revealed by Czech media contributed to realization that societal ties with Chinese entities should be treated with more caution in the future. The overall more skeptical climate regarding cooperation with Beijing in not only the US, but also the EU, especially after the Hong Kong protests in 2019 and revelation of human rights abuses in Xinjiang, reinforced the more reserved position of the Czech Republic. Lastly the coronavirus epidemic effectively wiped out incentives for cooperation, such as in tourism.

Eastern Promises No More

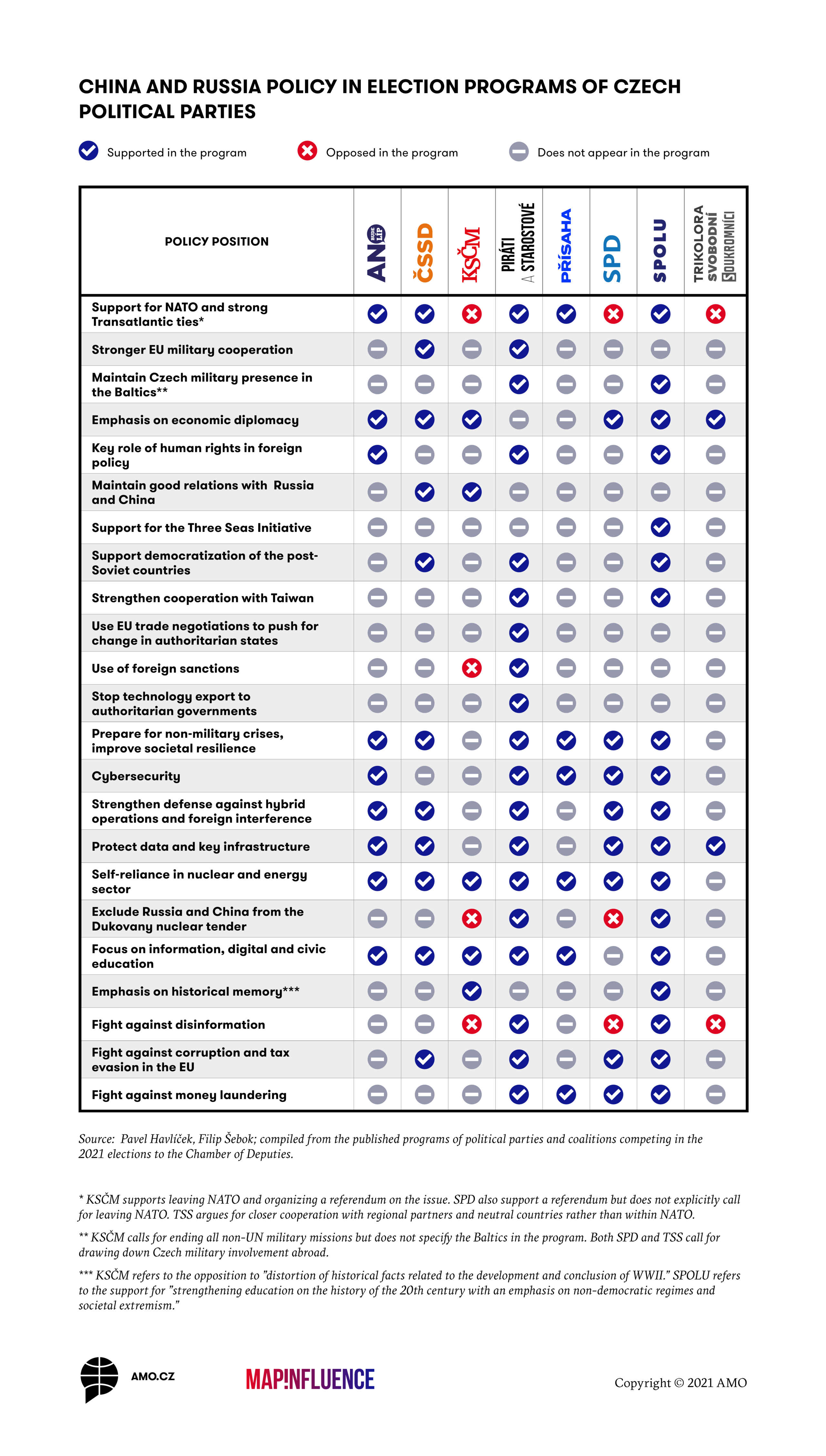

Czech political parties’ programs reflect this development and thus do not dwell too much on the issue of China both directly as well as indirectly. MapInfluenCE published a comprehensive summary of Czech political parties’ and coalitions’ election programs regarding both China and Russia. Of course, political programs are not necessarily full statements of the parties’ political positions on certain issues and actual foreign policy direction after the elections can look very different from the programs. After all, judging by the 2013 election manifesto of the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD), none could foretold that the party would spearhead the dramatic turn in the relationship with China in the government it led after 2014.

The program of the governing ANO party of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, which currently leads in polls, does not touch upon the China issue, merely asserting that human rights defense forms one of the traditional pillars of Czech foreign policy. In previous years, however, Babiš has been rather indifferent to China due to his negative experience doing business in the country and allowed other Czech players to develop China initiatives and policies of their own.

Thus, Czech foreign policy displayed an interesting array of actors and interests. One line on China policy has been conducted by President Zeman and through him via his advisors and China intermediaries. Another has been directed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs led by the Social Democrats, a minor coalition partner, with occasional intrusions of Prime Minister Babiš. The weak position of the MFA created a void which was quickly filled by yet another, this time individual, players like Prague Mayor Zdeněk Hřib or the Senate President Miloš Vystrčil. If ANO emerges victorious, it may be once again tempted to leave the portfolio to the junior coalition party.

The center-right coalition SPOLU (Together), formed by the Civic Democrats (ODS), TOP 09 and Christian Democrats (KDU-ČSL), has featured second in the most recent polls. The program of SPOLU mentions China or Russia on just a few occasions, both directly and indirectly. It argues for the diversification of the Czech export and strategic independence of Czech projects and companies (“we shall not be held hostage by risky countries, such as Russia or China”). The program also supports the exclusion of China from the buildup of the second bloc of the Dukovany nuclear power plant and mentions specifically the support of human rights issues. Other brief mentions are only indirectly linked to China as the program hits upon a cooperation on innovation with Taiwan, support for the Three Seas Initiative and battling against disinformation and hybrid threats (though without attribution to any state).

The coalition of the Pirate party and Mayors and Independents (STAN) has long been seen as a strong contender, however, it has been losing in the polls to ANO and SPOLU in the past few months. Its program specifically mentions support of civil society, independent media and dissent in authoritarian regimes, without linking it to China. The program also alludes to the need to support the Western Balkans and Eastern Partnership, and quite curiously, also cites the need for increased trade and “diplomatic” cooperation with Taiwan. A well-informed source within the Pirate party confirmed the coalition has not had a specific idea regarding the content of the increased diplomatic cooperation in time of writing the program.

Interestingly, none of the party and coalition programs surveyed for the article refer to the format for cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European countries (the so-called “16+1”). Given the fact that the Pirate party’s representatives have been rather vocal on the issue, it begs for explanation.

The plausible reasons for omitting the format from the programs range from general disinterest in the platform by the Czech public, to acknowledgement that the format is dead, to more mundane reasons such as the lack of space to elaborate on 16+1 in the foreign policy section of the program. In fact, the latter rationale was cited by a person from one political party responsible for the section.

Two other parties are likely to enter the Czech Parliament – the far-right SPD and far-left Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM). The SPD foreign policy program focuses mostly on the ‘Czexit’ from the EU, rethinking of participation in NATO missions abroad, cooperation with the Visegrád countries and migration. SPD’s long-term political program specifically mentions China in a small sub-section, praising the Czech President Zeman and his entourage for the development of bilateral ties. On its website, SPD calls the argumentation based on human rights abuses in China and Tibet as “naive”, closely connected to Czech domestic politics quarrels and damaging Czech economic interests.

The Czech Communists call for an exit from both the EU and NATO and simultaneously argue for improving relations with Russia and China. Economic diplomacy, according to KSČM, should assert Czech interests without any threats from the EU or the right-wing parties and without prejudice.

The analysis of the programs of various political parties and coalitions which compete in the Czech election points to a general disinterest in China among the voting populace. Despite previous instances of heated debates on the subject, China seems to fade away from political discourse just as quickly as it bubbles to the surface. In the end, society’s interests turn to post-coronavirus economic recovery and rising prices as the pressing issues of the election.

Nonetheless, whoever comes out on top will have quite a few tall tasks before them in the foreign policy arena. Given historical precedent, China is likely to be one of the primary issues to present itself.

Written by

Ivana Karásková

ivana_karaskovaIvana Karásková, Ph.D., is a Founder and Lead of CHOICE & China Projects Lead at the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in Prague, Czech Republic. She is a an ex-Fulbright scholar at Columbia University, NYC, a member of Hybrid CoE in Helsinki and European China Policy Fellow at MERICS in Berlin. She advised the Vice-President of the European Commission, Věra Jourová, on Defense of Democracy Package.