As a rising global power, China has been increasingly targeting the European and thus also the German market in recent years. Within the scope of its direct investments, its main focus is in particular on companies in the field of future-oriented key technologies. Germany, which is one of the world market leaders in many of these technology sectors, should position itself clearly in this regard and respond confidently to the immediate challenges associated with this shift.

Since the global financial crisis, China began to focus its foreign direct investments (FDI) to the European market. Among these investments, Germany belonged to the top destinations mainly due to its large and strong manufacturing base and leading technology companies. As a result, company takeovers by Chinese investors increased significantly up to 2016.

This development was followed with growing concern by politicians and the business community. China watchers warned that these takeovers were part of Beijing’s ambitious strategy to transform the People’s Republic into the leading powerhouse for future technologies. The media soon reported the “sellout of German know-how” and “shopping sprees.” In 2016, the largest share of FDI ever found its way from China into German companies. Subsequently, several well-known German businesses were taken over by Chinese investors. Among them was EEW Energy from Waste, the manufacturer of plastic processing machinery Krauss Maffei, and the industrial robotics manufacturer Kuka.

Meanwhile, the Kuka case has become the most well-known example and a watershed moment in the German discourse on China’s investment activities. The Chinese investors had always stated that they did not want to take over Kuka completely. Since May 2022, however, it has been official: Kuka will become 100 percent Chinese. Therefore, it is about time to review what has changed since the Kuka case in Germany’s China policy with respect to its (critical) key technologies.

Background of the Kuka Case

Kuka, a listed mechanical engineering company located in Augsburg, Bavaria, is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of industrial robots. In 2015, the Chinese electrical appliance manufacturer Midea initially acquired 5.4 percent of the voting rights, which the company expanded to almost 95 percent by 2016. With a transaction volume of around €4.66 billion, this was the largest corporate takeover of its kind to date.

As resolved at the Kuka Annual General Meeting in May 2022, the Chinese shareholders are now pursuing a complete takeover by a squeeze-out of the remaining smaller shareholders. Midea had already announced these intentions at the end of 2021, as well as its decision to delist Kuka from the stock exchange. In the future, the company and its new owners plan to invest significantly more in research and development and increase sales by 30 percent annually. Furthermore, it was agreed to keep the company headquarters and the jobs of the approximately 3,500 employees at the Augsburg location until at least 2025. Whether the new owners, located in the Chinese province of Guangdong, plan to relocate the entire site to Asia in the long term, will then be up to the Midea shareholders to decide.

However, alternatives would have been conceivable: Siemens was originally in talks to take over shares from Kuka but declined for financial reasons. Similarly, the mechanical engineering company Voith had the opportunity to increase its already existing shares in the company – or at least not to sell them. But in the end, no one was able or willing to outbid the Chinese offer.

The Kuka takeover has provoked extensive debates throughout Germany. Concerns were also expressed by the Federal Ministry of Economics. The then Minister for Economic Affairs Sigmar Gabriel, for instance, stressed the need to explore other options and to look for alternative opportunities in Europe. Similarly, EU Digital Commissioner Guenther Oettinger said that other offers should be considered – for example, by one of the other two major shareholders or via the participation of other European companies.

Beijing’s Hunt for German Industry Champions

This unusually clear response to the Kuka case on the political level must be considered in particular in the context of the strategy “Made in China 2025” (MIC 25) announced by Beijing just one year before the takeover bid. According to this strategy, Beijing defines ten key industry sectors where it strives to become the leading nation by 2025. Until 2049, the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic, China seeks to be the economic and technological hub of the world and perhaps even its political center. But before the US could be ousted from its leading position, China has to expand its economic outreach and strengthen its technological competitiveness. A crucial part of that endeavor is to take over innovative and future-orientated companies or at least control parts of them – this also applies to the world’s leading German companies in the field of key technologies and Industry 4.0. Simultaneously, Beijing wants to become mostly independent from foreign technologies and has begun to decouple itself from global value chains.

Since robotics is one of these key areas, the acquisition of Kuka is by no means a coincidence. In fact, according to a study by the Bertelsmann Foundation, 64 percent of the German companies sold to China between 2014 and 2017 belonged to the sectors prioritized by the MIC 25 strategy. Moreover, 17 of the 274 companies acquired by China can be found in the list of German world market leaders compiled by “Die Deutsche Wirtschaft.”

A similar development is also reflected in the Patent Index 2021. Although Germany ranks second in an international comparison with almost 26 thousand new patent applications every year, and is thus still ahead of China with its more than 16,500 patent applications, Beijing has caught up significantly with 24 percent more patents compared to the previous year – especially in what it defines as key technologies.

In addition to Kuka, ChemChina acquired the mechanical engineering company Krauss Maffei for more than €1 billion in the same year. ChemChina is one of about one hundred Chinese companies that belong to the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) which was founded in 2003 and is directly subordinate to the State Council of the People’s Republic. These close ties between companies and the Chinese central government are not uncommon and repeatedly lead to distortions of competition. Behind these formal institutions and structures, it is the Chinese Communist Party that ultimately pulls the strings.

While other well-known German companies were subsequently sold to Chinese investors (including Biotest and Ista), there were also cases in which takeovers were successfully prevented. These included the electricity transmission system operator 50Hertz, for which, however, a “special solution” had to be found by the government due to a lack of an appropriate legal basis, as well as the communications technology company IMST. It was only in April 2022 that the German Federal Ministry of Economics also stopped the takeover of the manufacturer of respiratory equipment Heyer Medical. But what has changed since Kuka?

From German Sleepwalking to a Techno Strategic “Zeitenwende”?

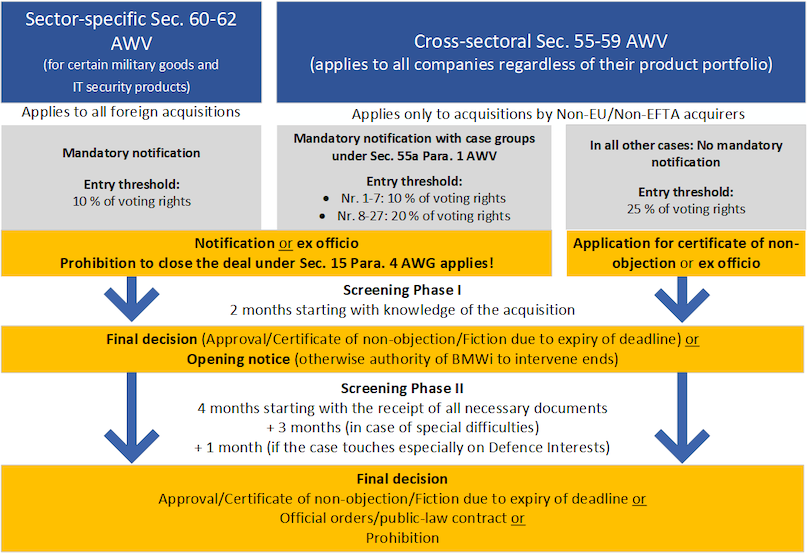

The Kuka takeover, which ultimately could not be prevented, is regarded as a turning point at the political level to rethink the consequences of selling-out critical German know-how to China. Thus, the German government began to revise its legal framework to prevent similar cases in the future. In addition to an extension of the screening periods, the threshold for the review of companies that are particularly relevant to security was lowered from the previous 25 to 10 or 20 percent (depending on the sector as illustrated in the following figure).

For all other sectors, however, an investment screening of 25 percent or more continues to apply, as provided for in paragraphs 55a and 56 of the German Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance (Außenwirtschaftsverordnung, AWV). In any case, in order to prevent a takeover, the Federal Ministry of Economics must determine a “probable” threat to public order or security (previously, a “real” threat had to be determined for this step).

However, it remains questionable whether the aforementioned changes of the legal framework could have prevented the takeover of Kuka. Since Kuka does not produce any goods that endanger public order or security, a corresponding justification with reference to the AWV would still be difficult to make.

German Investment Screening Process

Furthermore, measures have been taken also at the EU level in recent years. On the initiative of Germany and other EU member states, the EU Commission launched an EU-wide FDI screening mechanism that was introduced in 2019. The aim is to create a uniform legal framework for all member states to make takeovers more transparent and to be able to more easily restrict the free movement of capital from third countries. However, many other countries including China already implemented an investment control procedure. Besides, the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) between the EU and China concluded at the end of the German EU Council Presidency in December 2020 was initially considered a great success. However, only five months later, the ratification talks on the CAI, which had been negotiated since 2013, were put on hold for the time being when China imposed reciprocal sanctions against the EU.

German Dilemmas

The Kuka case is only the most prominent example of Germany’s much bigger dilemma: its close economic ties to and dependency on China and the need to find a realistic strategy to cope with a more aggressive competitor and systemic rival as the EU Commission and the new German governing coalition described it. Concerned about possible negative consequences, German lawmakers shied away from formulating clear red lines towards China such as taking stricter measures regarding the unequal competitive conditions and market access, preferring to avoid tough decisions. This became particularly evident in the discussion over the question of whether Huawei should be involved in the German 5G network expansion.

The People’s Republic plays a significant role for Germany as its most important trading partner. Access to the huge Chinese market continues to be of utmost importance for Germany as an export nation. However, there are growing concerns about a lack of reciprocity and unequal competitive conditions as well as a loss of key technologies and know-how. In this conflict between protecting national interests and strategic companies on the one hand and not jeopardizing relations with China on the other hand, it is, however, important for Germany to take a strong stance – at best without entering into a new stage of protectionism and sanctions. The tightening of the legal framework can therefore be interpreted as a clear signal in this regard and is a key element of a German and common European China strategy that needs to be developed.

At the same time, Germany must not underestimate its economic relevance for China – Beijing has been heavily dependent on German know-how and access to key technologies so far, particularly for achieving the MIC 25 strategy. In this sense, Germany should confidently safeguard its interests in dealing with China. Long-term stable bilateral relations can only be built on equal opportunities and rights. Russia’s war on Ukraine has demonstrated that Germany’s naïve “change trough trade” policy did not work out and backfired. In order to avoid a similar harsh awakening towards China, Germany has to see the relationship in geostrategic terms and should decrease its dependencies in the light of future contentions – the next Kuka case might just be around the corner.

Written by

Cynthia Wrage

Cynthia Wrage is a Research Associate and PhD candidate of political science at the department for Comparative European Governance Systems at Chemnitz University of Technology, Germany.

Jakob Kullik

Jakob Kullik is a Research Associate and PhD candidate in political science at the department of International Relations at Chemnitz University of Technology, Germany. He is a member of the Young Foreign Policy Experts of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung and a member of the Young Security Experts of the Federal Academy for Security Policy (BAKS).