The recently concluded NATO summit has reinforced Chinese authorities’ belief that the Alliance activity with partners in the Indo-Pacific is part of the US hegemonic interests. In an effort to counter this, China is developing a narrative of NATO as a destabilizing actor while strengthening its military capabilities, including in cooperation with foreign partners.

The excerpts from NATO‘s Vilnius summit communiqué on China reiterate the key points of the Alliance’s Strategic Concept updated in 2022. The document emphasizes the need to counter Chinese coercion, disinformation, and hybrid operations which pose an urgent threat to the interests, security, and values of the NATO member states.

For NATO countries, Beijing’s policies destabilize the situation in Europe and may negatively affect the development of the Alliance’s deterrence against Russia.

From China’s perspective, the Alliance’s China policy as defined by the Vilnius summit is another expression of a change in NATO policies resulting from the US influence and inspiration. NATO is, in this context, one of a plethora of American instruments employed against China globally.

In terms of propaganda narratives, Chinese politicians and experts try to demonstrate the ‘real’ – offensive and destabilizing – character of NATO. A special place in this narrative is given to the changes in the Alliance’s relations with the Indo-Pacific states, as also evidenced by the presence of the leaders of Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea at the Vilnius summit. At the same time, China has accelerated the development of its power projection capabilities and a possible response to NATO engagement. One element of this development is cooperation with Russia and other foreign partners.

NATO as a War Machine

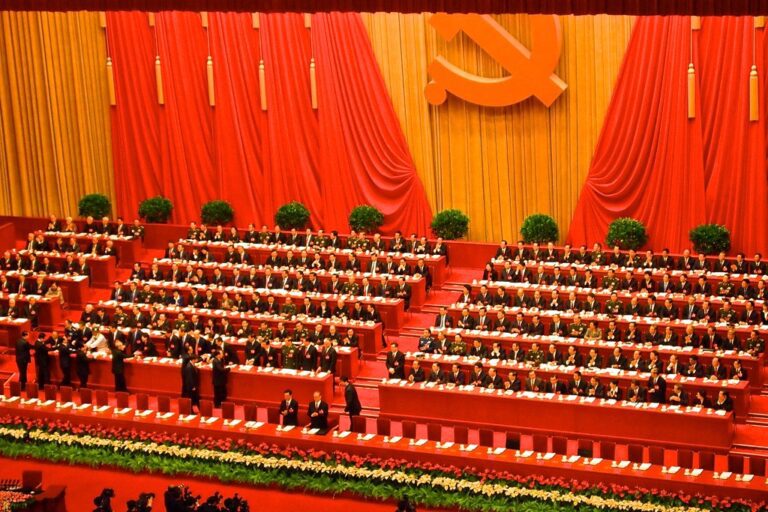

China’s narrative of the offensive and destabilizing nature of NATO’s actions did not appear overnight. Since the end of the 1990s, it has been an important element of the CCP’s nationalist policy calculated to strengthen the mobilization of Chinese society in the face of growing rivalry with the US.

The symbolic element used by the Chinese authorities to create such a narrative was the bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade by NATO aircraft in 1999, in which several Chinese citizens were killed. Less symbolic but a practical argument here was the enduring role of the Alliance after the end of the Cold War, or the course and consequences of the intervention in Afghanistan (albeit initially supported by China).

The destabilization narrative also involves – of particular interest in the Ukrainian context and its potential membership in the Alliance – China’s criticism of the gradual enlargement of NATO, especially the inclusion of Central and Eastern European states, who, in China’s optics, remained in the Russian sphere of influence. NATO was always regarded in this context as a “hegemonic tool of the USA”, or as it was once described by China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson and repeated by China Daily Brussels correspondent: “a war machine”.

China’s policy towards the Alliance was not always clear-cut, especially as there was also a lack of unified assessment in China as to the continued functioning and aims of NATO after the end of the Cold War. This meant that in the early 2000s, there were also plans on the Chinese side to develop relations with NATO, for example in the form of creating a permanent dialogue between China and the Alliance. The US-China rivalry and its intensification towards the end of Barack Obama’s presidency linked to Beijing’s increasingly assertive foreign policy meant that gradually, the narrative on NATO merged with that on the US.

NATO and the Pacific

In Chinese optics, the Vilnius summit and its decisions are another stage in the creeping political and military process, in which NATO is pursuing (at the instigation of the US) its global ambitions by encircling China (and its partners like Russia), above all in the Indo-Pacific.

Seen from China, NATO is refocusing on its Cold War aspirations, seeking expansion and creating new problems for the world and especially Europe, also in terms of the nuclear threat. Therefore, Chinese experts accuse the Alliance of seeking to prolong the war in Ukraine as a tool to fight Russia, while, if needed, an active direct military intervention would allow the Alliance to defeat the Russian Federation and end the war.

Moreover, China finds the attempts to link the support for Ukraine with strengthened engagement with Taiwan as a deliberate US move to force European partners (which, after all, the Chinese claim, do not want to engage on Taiwan) to get involved in both theatres and support the US initiatives.

Crucially, the Chinese narrative of an ‘offensive NATO’ is not only about rivalry with the US but also about encouraging transatlantic rifts and moving the European allies away from the US. This effort is supported by narratives claiming that building a European security solely on guarantees from the United States contradicts the idea of European strategic autonomy and, therefore, the EU’s political weight on the international stage. China saw the desired fruits of its narrative when France blocked the initiative to establish a NATO office in Japan at the Vilnius summit.

China’s narrative does not only entail a negative agenda, criticizing NATO for destabilization, but also a positive one, intended to promote Beijing’s international initiatives, mainly in the so-called Global South. This is particularly true of the Global Security Initiative (GSI), which, according to Chinese interpretation, would, unlike NATO, realistically guarantee peace and security for the states subscribing to it.

One of the points raised in this context by Foreign Minister Wang Yi during his recent meetings with the ASEAN countries is the portrayal of NATO’s involvement in the region as geared not to the development and prosperity of all states, but to the “realization of the demands of a few states for absolute security.” The “indivisible security” concept, once designed in Helsinki Accords, has been revived in China-Russia relations as the argument for legitimate reasons for countries to engage in offensive war. The concept provides justification for Russia for its aggression against Ukraine but has also been borrowed by the Chinese in the GSI and appears to be one of the foundations of the China-Russian relationship.

Hence, the political dimension of the damage to the Chinese consulate in Odessa as a result of the Russian shelling of the city in July is a low-ranking event compared to the destruction of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. Despite the obvious differences (three Chinese citizens were killed in the accidental attack in Belgrade), both events have one point in common of formal and political significance – the buildings of the Chinese diplomatic mission were damaged by a third country. Yet, while in 1999, China’s Foreign Ministry asked the Alliance (and the US) about the violation of Yugoslavia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, nothing of the sort happened in 2023. Instead, China’s Foreign Ministry is blurring the question of the responsibility for the attack, emphasizing the possibility of the (self-induced?) “explosion” near the consulate, but especially the maintenance of communication with both sides and concern for the safety of Chinese citizens.

Active Capacity Building

China’s engagement towards the ‘pacification’ of NATO represented at the Vilnius summit is not limited to the narrative arena. At the same time, a reconstruction of Chinese armed forces is underway, both in terms of force projection, structure, equipment and operational plans, but also in terms of political loyalty and ideological mobilization. While the moves are not directly NATO-oriented, they do have an influence on NATO’s capabilities and member states policies.

In June 2022, Xi Jinping signed relevant ordinances that provide legal underpinning for the Chinese armed forces to conduct “other than war” operations outside China. During the recent Politburo session, he stressed the importance of reforming the armed forces, including in terms of governance and obedience to the Party. At the same time, more naval vessels are being built (the goal is to achieve a navy of more than 400 ships by 2025), Chinese naval forces regularly train with the Russian navy, and the Chinese military’s port and operational base infrastructure in the Pacific is expanding. In July this year, further agreements were signed with the Solomon Islands, and in addition to the base in Djibouti, four more are possible by 2030 (plus port infrastructure in Cambodia, among others).

The EU Factor

The Chinese authorities are convinced that there is no going back for NATO’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific, which is a direct consequence of the US political-military objectives of which the Alliance is an extension.

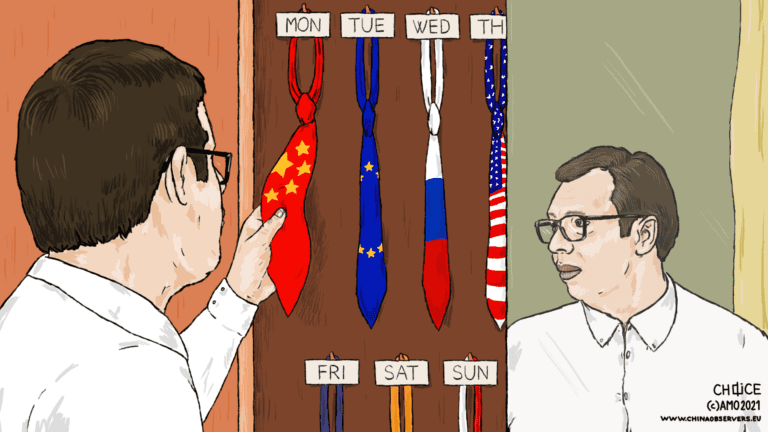

For Beijing, the objective of reducing the effects of NATO’s interest in the Indo-Pacific region can be achieved mainly by political measures, including by dismantling of transatlantic cooperation and the strengthening of the European Union’s sense of autonomy, also in terms of pursuing its security.

Downgrading the significance of Russian aggression, and trying to return to a normal relationship with the EU while supporting Russia are also Chinese tools to erode the coherence of NATO vis-à-vis Russia, but ultimately also vis-à-vis Chinese interests in the Indo-Pacific.

In this context, EU and NATO member states’ engagement in political relations with partners in the Indo-Pacific is key. That does not mean that an additional dimension should not be the development of defensive and offensive capabilities in the region in order to deter the possible Chinese future operations, whether against Taiwan, Japan, or in the South China Sea and East China Sea.

Written by

Marcin Przychodniak

Molos123Marcin Przychodniak is an Analyst at Asia-Pacific program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), focusing on Chinese politics and a former diplomat in Beijing.