Chinese Investments in the Czech Republic: Opportunity or Threat?

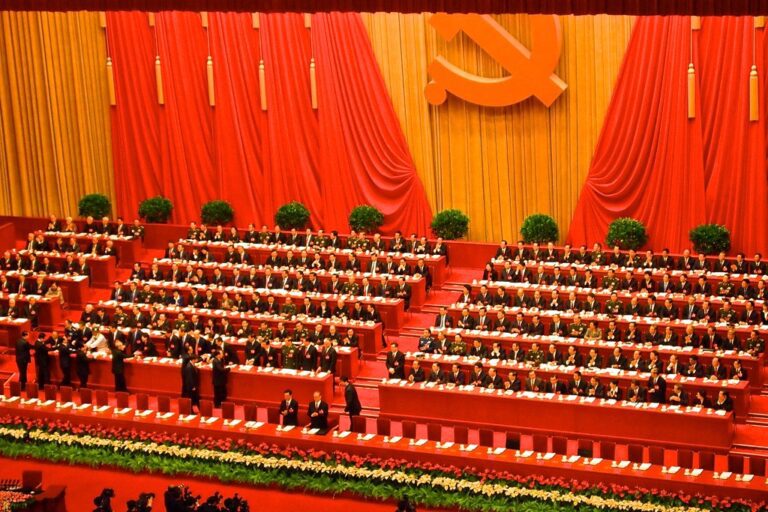

Before 2015, the idea of China-Czech cooperation was a non-issue. Relations hung in a post-1989 fog of mutual disinterest and distrust, dominated by the Czech preference for prioritising Havelian anti-communism and human rights and engagement with Taiwan over contact with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Then, seemingly out of the blue, there was contact, and very cosy contact at that: in September 2015 President Zeman popped up in Beijing, the only EU leader present at a military parade to celebrate the end of the Second World War, signing agreements for a raft of Chinese investments in Czech firms. He also announced that the head of the private Chinese investment company CEFC China Energy, Ye Jianming, had become his personal advisor. Zeman’s trip to China was followed up with a reciprocal visit by Xi Jinping to Prague in March 2016, during which beer was quaffed in a comradely fashion and more investment agreements were signed. CEFC was a leading investor in many of the deals.

The Mysterious Tale of CEFC’s Czech Investments

Observers wondered what had happened to inspire such a high level of guanxi – the Chinese concept of good personal relations for the purpose of generating business cooperation – between the Czech and Chinese presidents. They also wondered what exactly CEFC’s role was in the affair. It appeared that Ye Jianming’s company was acting as a broker of deals on behalf of the Chinese state, with close coordination between him, President Xi, and President Zeman.

Among the deals announced in 2015 and 2016 were Chinese investments in the Czech companies Travel Service (an airline), Lobkowicz (a brewer), Empresa (a media conglomerate), Invia (a travel agent), Slavia Prague (a football club), and some real estate in downtown Prague. CEFC had reportedly also acquired a 50 per cent stake in J&T, a Czech/Slovak finance company. Overnight, and from a previously very modest level of investment, China had become a major player in the Czech Republic; and CEFC and its CEO apparently had a key role to play as an intermediary.

The assumption of course was that CEFC had been endorsed by Beijing and was enacting Chinese state policy. However, the reality was to turn out to be surprisingly different.

By 2018 things had gone very sour – and gone south fast. First, the Czech media, instinctively suspicious of the Chinese presence, had pointed out that levels of Chinese investment were not reaching the promised heights. Then it emerged that Ye Jianming had been detained in China after his chief financial officer, Patrick Ho, had earlier been arrested in New York for bribing African officials – a crime of which he was convicted in 2019. By the middle of 2018 it also became known that CEFC had not fulfilled its financial commitments to the Czech companies in which it had bought stakes and owed large sums of money. Suddenly the notion that CEFC was under the control of the Chinese state seemed fanciful: how could the company have been enacting Xi Jinping’s will if its CEO was under arrest and it had not paid its debts, leaving the Chinese government with a mess on its hands and a stain on its reputation to boot? The mystery was hard to fathom.

At this point, in mid-2018, the Chinese sent in the cavalry. The state-owned investment company CITIC paid off CEFC’s unpaid debts and took over its investments in an attempt to settle Czech nerves and repair the reputational damage. To an extent these damage control measures, which had become embarrassing to both governments, were successful in bringing the affair to a resolution amenable to the two sides. However, no major new Chinese investments were announced in the aftermath of the CITIC intervention. It seemed the Chinese had decided merely to fulfil the existing financial obligations but not to add to them.

Overall, the evidence of the years 2015-2018 demonstrates that the theory that the Chinese state had been fully in control of investments made by a Chinese private company was false. Instead, a better framework for studying Chinese activity turns out to be the economic theory of principals and agents. In essence, the interests and activities of CEFC – the agent apparently charged with delivering results – diverged significantly from what was expected by the principal, the Chinese state. The consequence, when things broke down, was that the state had to step in and clean up the mess made by its obviously out-of-control agent. The notion of measured and controlled state planning of investment activities by Chinese commercial actors in overseas settings is therefore thrown into doubt.

Why CEFC Anyway?

What remains uncertain are the reasons behind CEFC’s involvement. Why was this private company, which had conjured its empire out of thin air via a pyramid scheme of dubious financing which eventually collapsed, entrusted with such a key role as an intermediary between Beijing and Prague?

One possibility is that CEFC offered some financial inducements in order to get access to the Castle, but it is important to state clearly that at the time of writing no evidence of such activity has emerged. However, there clearly must have been some kind of guanxi established between Ye Jianming and Czech agents such as former minister of defence Jaroslav Tvrdík, who was given the role of vice-chairman of CEFC’s European operations. In 2016 Tvrdík became the Chairman of Slavia Prague FC – a role which he retains at the time of writing, despite the controversial withdrawal of CEFC and their replacement as majority owners by CITIC. Slavia was acquired amidst a flurry of Chinese investments in European football clubs. The alleged reason for this spate of acquisitions – including Inter Milan and AC Milan was Xi Jinping’s apparent love of the sport. Ultimately, Slavia Prague remains in Chinese hands under the leadership of the man who brokered deals between CEFC and the Czech government.

The CEFC affair demonstrates that Chinese overseas investments under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are not necessarily under the full control of the Chinese government. The agents employed as intermediaries may have interests which are at odds with Beijing’s aims, resulting in unpredictable outcomes. It is highly likely to be the case that many transactions which are listed as BRI are the result of backroom negotiations involving both Chinese and non-Chinese business people trying to turn a profit. In other words, the path to China’s New Silk Road does not always run smooth.

The Relationship Turns Sour

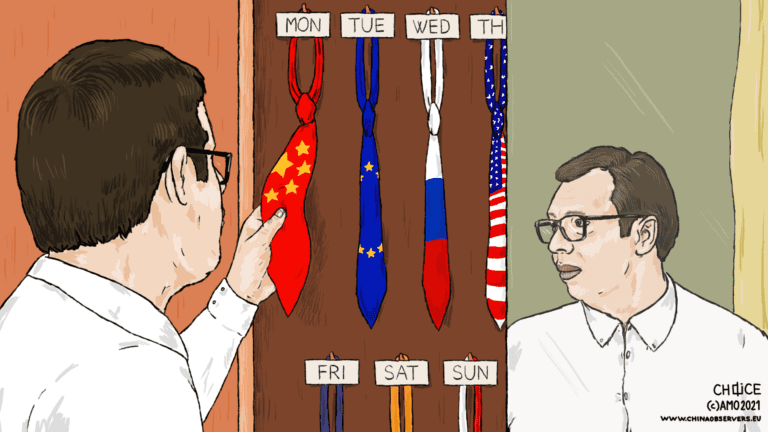

There is a coda to this tale of unfulfilled expectations and breakdown in trust. The faith of Czechs in the sudden increase of Chinese economic and political activity in their country had never been strong in the first place. As the narrative of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ grew into a global backlash against China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the proposal that the Chinese mega-corporation Huawei should provide key IT technologies to the Czech Republic began to be treated with even greater suspicion. The media examined links between the Chinese state and Czech institutions. It was discovered that the foremost Czech university, Charles University, had hosted a conference which had been funded by the Chinese embassy, with a private company set up by the organiser, Miloš Balaban, receiving the Chinese funds. The rector of the university had to apologise and promise an investigation in order to see off the subsequent media fallout from this incident; but in the eyes of the large sections of the Czech public it was further evidence of Chinese attempts to meddle in the institutional fabric of their society. Since freedom from communism had been won only after long years of repression, people were not willing to contemplate the slightest hint of its politicians and scholars kowtowing to a state whose leaders still portrayed themselves as Marxists. By early 2020, even President Zeman was expressing doubts about the wisdom of investing so much emotional capital in the Chinese, announcing that he would not attend the 17+1 summit in Beijing in order to send a clear signal to the Chinese leadership thathe considered their promises of investments to be unfulfilled.

At the time of Xi Jinping’s visit to Prague in March 2016, the prevailing narrative in Czech-China relations had been one of opportunity: the two countries could establish mutual cooperation and transform what had previously been a frosty relationship through Chinese investments and enhanced economic ties. By late 2019, this narrative had completely collapsed amidst recriminations over perceived political interference and disappointment at the low levels of Chinese investments compared to those that had been promised. The opportunity narrative had been replaced by the more familiar China threat hypothesis.

The tale of Czech-China relations between 2015 and early 2020 is thus one in which the Chinese attempt to cultivate its junior partner through promises of win-win economic cooperation has been an abject failure. Not only did the Chinese fail to enhance relations – their activity has actually caused Czech perceptions of China to deteriorate markedly, with 57 per cent of Czechs perceiving China unfavourably in 2019. Little now remains of the optimism generated during the signing of agreements and drinking of beer in Prague Castle in 2016. In February 2020 it is difficult to see how the damage caused to China’s reputation by its poor investment record and perceived political interference in the Czech Republic can be quickly – or even slowly – repaired.

Written by

Jeremy Garlick

jeremy_garlickJeremy Garlick is an Associate Professor at the Department of International and Diplomatic Studies, Prague University of Economics and Business. He is also the Director of the Jan Masaryk Centre for International Studies, a research institute within the Faculty of International Relations, and a member of the Horizon Europe project European Hub for Contemporary China (EuroHub4Sino). His research focuses on China’s international relations, concerning which he has published three books and numerous peer-reviewed papers.