When Donald Trump and Xi Jinping met at the APEC Summit in Busan in October, the atmosphere was more weary than historic. What might once have been a spectacle of competing grand strategies, was now predominantly an encounter between two leaders burdened by the economic consequences of their own decisions on the mutual tariff walls, export controls, and tit-for-tat restrictions on technology and critical raw materials.

In a broader sense, the relationship between Washington and Beijing has become a paradox as every attempt to separate the US and China’s economies only reveals how deeply intertwined they are. Bound by trade, technology, and finance, neither can meaningfully hurt the other without hurting itself. After all, the US and China in their current state seem to remain products (and prisoners) of the same global economic system that has been powering their rise for the past decades.

Putting On a Brave Face

The US and China enter this subsequent phase of negotiations carrying different burdens but similar dilemmas. The US faces inflation, mounting debt, and the societal and economic costs of re-industrialization. China struggles with the so-called involution (內卷, a state of excessive competition and pressure that doesn’t lead to progress), growing youth unemployment and the long shadow of its real-estate crisis.

In Trump’s Washington, tariffs became a political weapon, a show of toughness and determination, even if they raise prices for consumers and create uncertainty for the American industry. In Xi’s Beijing, increasing control is the preferred remedy: introducing deeper export restrictions, tighter Party oversight, and renewed emphasis on ideological unity. Although some of these measures have been introduced even before the start of the US-China trade war in 2018, their scope and intensity have been amplified by the acceleration of this rivalry.

Each path carries its own cost. Together, they form a cycle of economic self-punishment, where both powers are willing to weaken themselves and accept domestic struggles if it means holding the other one back. What emerges between the lines of American and Chinese official narratives of strength and resilience is a competition where power is measured not by growth or innovation, but predominantly by how much hardship each side can endure.

Paradox of Interdependence

This situation is not an accident of the present, but a legacy of a particular model of global economic development. After joining the WTO in 2001, Beijing pursued an export-driven industrial policy, attracted immense foreign investments, and was relentlessly developing the country’s infrastructural base. As a result, China became the “world’s factory,” powering the global manufacturing and supply chains. On the other hand, Western trade liberalization, offshoring, and liquidity abundance provided the demand and finances to keep the system running.

For years, this arrangement worked for both sides and the West enjoyed cheap goods, low inflation, and a prolonged sense of prosperity. This system also provided a buyer for Western currencies, mainly the dollar, but to an extent the euro as well, which allowed governments to print more money and run persistent deficits without fear of default or hyperinflation. As long as others, in this case China, held their debt, the West could consume more than it produced and still feel secure. Thus, consumers benefited from lower prices, while Western companies were able to increase margins and reap profits. Beijing, in turn, gained access to Western markets, technology, and investments, transforming itself from an impoverished industrial periphery into the engine of global supply chains, which allowed for lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in the process.

For a time, it appeared to be the perfect equilibrium. Some in the West perhaps assumed that China, similarly to the Soviet Union in the past, as a socialist state, would be unable to innovate because centrally planned economies, by nature, provide less incentives for competition and development. The expectation was that China would continue producing goods designed and engineered in the West. This assumption proved overly confident. China did not fully break the system of socialist constraints but it learned how to use it more effectively, creating a “party-capitalist” structure, gradually moving up the pecking order, and challenging Western dominance in areas once considered secure, such as R&D or engineering. The result was the beginning of a long structural rivalry, one that we see unraveling today.

Two Weary Superpowers

The Xi–Trump encounter in Seoul reflected this reality. Polite handshakes, assurances of cooperation, and statements of a long-time friendship between the leaders dominated the scene. Behind closed doors, familiar topics surfaced: trade, technology, and global supply chains. As a result of this meeting, Trump promised to lower tariffs on imports from China and stated that the agreement includes “a commitment from China to purchase soybeans from American farmers, curb the flow of fentanyl, and postpone its export restrictions on rare earths.” On the other hand, Xi spoke in much less of a detail, highlighting the need for dialogue and possible non-political venues for US-China cooperation, such as combating illegal migration, infectious diseases, and telecommunications fraud. He also emphasized that next year, China will hold the informal meeting of APEC leaders, whereas the US will host the G20 summit. This may have been intended to signal parity between China and the US and serve as an acknowledgment of their shared status as the world’s leading powers.

All in all, neither Trump nor Xi offered any new ideas, only quiet reassurances that their confrontation would stay under control. The meeting felt like a planned pause as both leaders sought to manage tensions rather than resolve them. This shows how weary both superpowers have become. Both of them look for compromise while persistenly projecting confidence, claiming they can hold out longer than the other, even as their own weaknesses deepen. The rivalry endures not because it brings advantages, but because neither side can imagine how to end it and what may come after it.

Way Forward?

The Xi–Trump meeting in Seoul was a mirror reflecting two tired giants trapped in their own strategies, each too invested in their game to admit its limits.

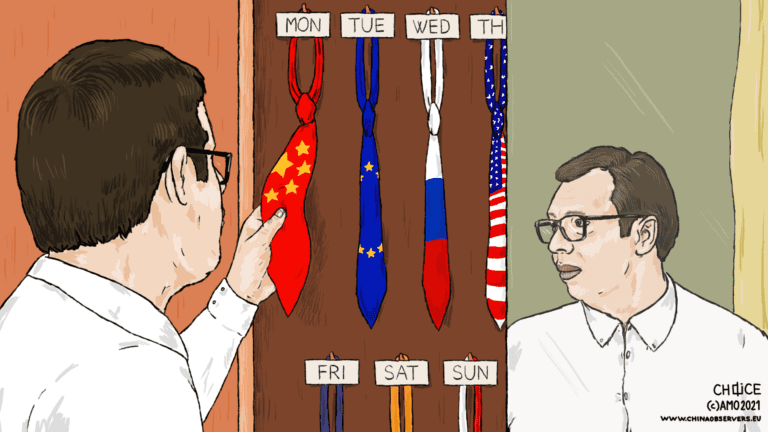

The paradox of this moment is stark. The United States and China are bitter rivals who depend on one another, “partners” who compete, and big powers that can wound but not replace each other. Both claim to be winning, yet both are slowly undermining the very system that made their dominance possible. They are, in many ways, winners of a system they can’t escape – locked in a structure that rewards their success but punishes their attempts to outgrow it.

In the end, the world’s new equilibrium may rest not on strength and development but on the fatigue of two giants tied in a gordian knot of a global economic structure they were instrumental in creating. Neither can afford to break the knot, nor truly escape. At least not yet.

Written by

Konrad Szatters

Konrad Szatters is a China Analyst at AMO, focusing on China’s political discourse and foreign policy. He also serves as a Lead Researcher for the Ukrainian Heritage Diplomacy in China at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand. Previously, he gained experience at the College of Europe in Natolin, the Polish Diplomatic Academy, and the Embassy of Poland in Beijing.