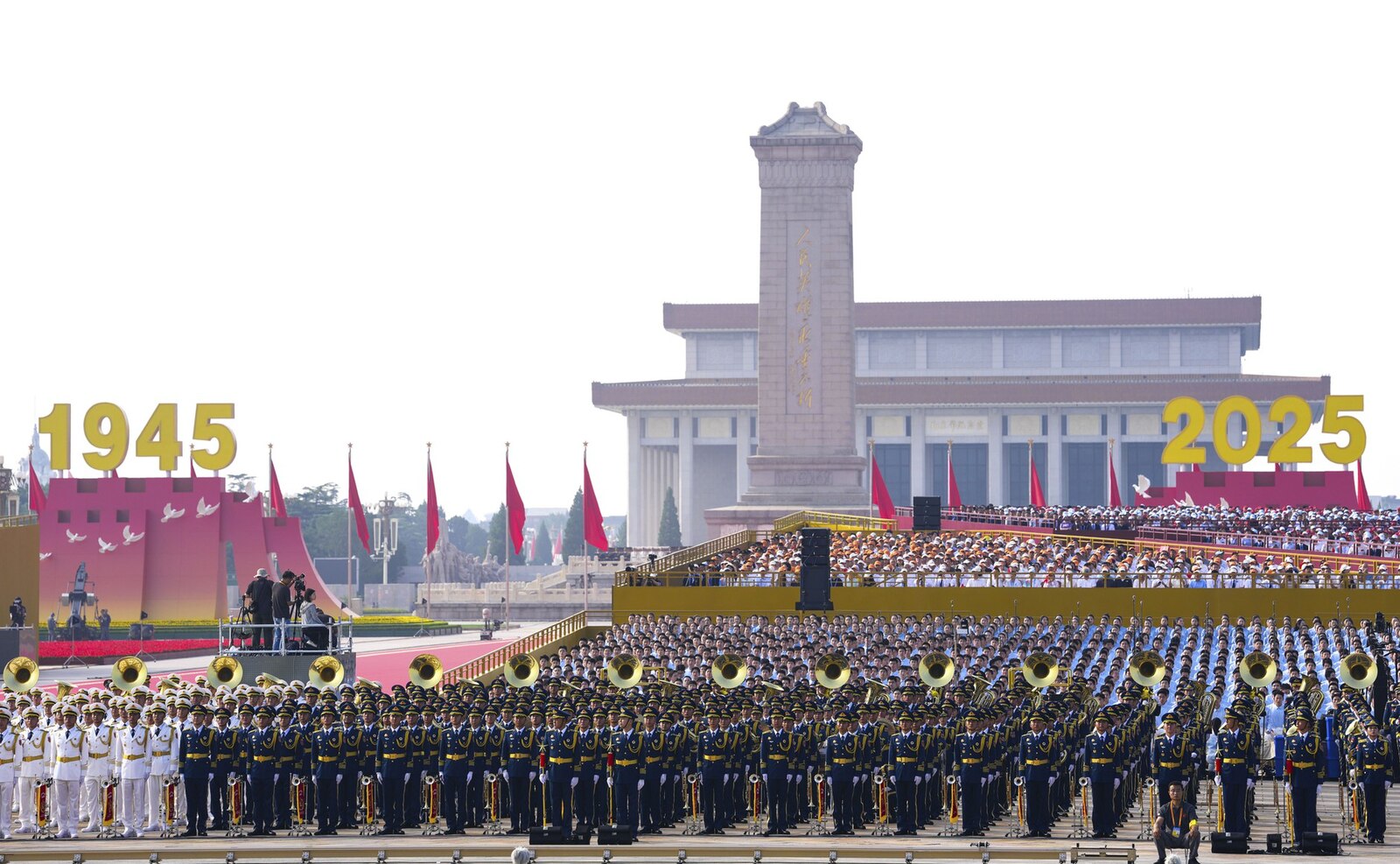

On September 3, 2025, decorative white doves adorned the giant numbers “1945” and “2025” during Beijing’s military parade along the Avenue of Eternal Peace. Overshadowed by the tanks and missiles rolling past, these cliché symbols of peace seemed paradoxical. Yet this juxtaposition was repeated throughout September, as China orchestrated large-scale events with two seemingly contradictory goals: demonstrating overwhelming military might while positioning itself as a leading force for peace in an alternative world order.

The military parade showcased the results of the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) modernization, including an unprecedented public display of China’s nuclear arsenal. Two weeks later, at the Xiangshan Forum, defense minister Dong Jun delivered a speech outlining China’s intentions regarding Taiwan and the South China Sea, while also declaring that “the stronger the Chinese military grows, the stronger the force for peace will become.” Why, then, does China paint doves on its tanks? What does this dual narrative reveal about Beijing’s strategic vision for regional dominance? And what exactly is “peace with Chinese characteristics”?

Flexing Military Muscle: A Showcase of Modernization

The lavish military parade – estimated by Taiwanese officials to have cost 36 billion yuan ($5 billion), roughly 2 percent of China’s defense budget – served a clear purpose. While the official figure has not been confirmed, Beijing clearly spared no expense to showcase the PLA’s modernization. This is significant as the event came after a year of speculations about the PLA’s operational readiness. High-level purges of PLA officers, including several handpicked by Xi Jinping in 2022, sparked rumors of Xi’s distrust in his generals. Combined with the PLA’s lack of experience in high-intensity conflict since the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War, doubts grew over its actual combat capability.

Marking the 80th anniversary of China’s victory in the war of resistance against Japanese aggression, the parade sought to dispel these doubts, signaling progress toward Xi’s 2027 deadline for PLA modernization and combat readiness – including a possible invasion of Taiwan. Taiwan reacted swiftly, with President Lai Ching-te asserting: “The people of Taiwan cherish peace, and Taiwan does not commemorate peace with the barrel of a gun.” Clearly interpreting the parade as a military intimidation and a cognitive warfare move against Taiwan, Lai further warned that the “security environment” in the Taiwan Strait was “more severe than ever before.”

For the first time, China openly displayed its nuclear triad – land, air and sea systems. Five long-range systems capable of striking the continental United States were presented, signaling a deterrent posture to dissuade intervention in the event of a Taiwan conflict. China’s arsenal has doubled from 300 nuclear weapons in 2020 to an estimated 600 in 2025, and the US Department of Defense estimates that it will reach 1,000 by 2030. Equally important was Beijing’s effort to position the PLA as a leader in technological innovation. Featured high-tech systems included laser weapons designed to counter drone attacks – widely interpreted as a response to Taiwan’s plan to purchase 50,000 drones over the next two years, inspired by Ukraine’s defense strategy.

Three new PLA branches also made their parade debuts: the Information Support Force, the Military Aerospace Force, and the Cyberspace Force. Their display of high-tech AI-powered weapons – an answer to assumptions of American dominance in this sector – included unmanned vehicles capable of reconnaissance, assault, mine and bomb defusing, and squad support, as well as uncrewed tanks operating in formation with robotic wolves and small combat vehicles launching drones for coordinated air-ground operations. These advances reflect the Made in China 2025’s focus on “new quality productive forces” – that is, high-quality, high-tech production capacity that now extends to military applications.

China’s official defense budget reached $247 billion in 2025, though actual expenditures are estimated between $318-471 billion. The PLA Navy already surpassed the US Navy in battle force ships in 2014 and continues to grow. This growing military footprint is underscored by Beijing’s increasingly firm and affirmative rhetoric, as illustrated by Dong Jun’s keynote at the Xiangshan Forum, during which he declared Taiwan’s “return to China as an essential part of the post-war international order,” warning that the PLA “will ensure that no separatist attempt at Taiwan independence succeeds and is ready to deter external military intervention at any time.” On the South China Sea, Dong dismissed “so-called freedom of navigation” and “international arbitration” as challenges to international norms.

Weapons in Hand, Peace on the Lips: The Xiangshan Forum

The 12th Beijing Xiangshan Forum – taking place between September 17-19 – convened under the theme “Upholding International Order and Promoting Peaceful Development.” With record attendance of 1,800 participants from over 100 countries – compared to 500 from 90 countries in 2024 – the forum presented China as a stabilizing global force. Yet Western engagement dropped sharply: the United States downgraded its representation from assistant secretary of defense in 2024 to defense attaché in 2025, with most Western allies following suit.

Xiangshan served as China’s counterweight to the Shangri-La Dialogue, where French President Macron drew explicit parallels between Russia and China as “revisionist countries” seeking to impose “spheres of coercion.” Macron also compared territories “from the fringe of Europe to the archipelagos in the South China Sea,” asking what the international community would do “the day something happened in the Philippines” or Taiwan.

Xiangshan offered an alternative narrative: China as an upholder of international law and a champion of dialogue. Despite limited Western participation, the forum highlighted “praise” from figures like Jean-Pierre Lacroix, UN Under-Secretary-General for Peace Operations, who commended China’s peacekeeping training, while Jean-Christophe Baron von Pfetten of the Royal Institute for East West Strategic Studies (nicknamed the red baron for his long-standing ties with Beijing) declared “China is becoming the center for dialogue – where else can you find officials from NATO, Russia, Ukraine, Palestine, and Israel all in one place?”

The forum also provided an opportunity to showcase Beijing’s recent rhetorical shift on the Israel-Palestine conflict. China condemned Israeli actions while supporting the two-state solution – a low-risk but potentially viral stance that contrasts sharply with current US positions at the UN.

Peace with Chinese Characteristics

In his parade address, Xi Jinping mentioned “peace” (和平) six times – three fewer than in his 2015 speech. Nonetheless, framing China as a “force for peace in the world” remained central to Xi’s rhetoric. Xi has long linked China’s vision of peace to Confucian thought. Back in 2014, at an academic symposium on Confucius, Xi noted that “peace-loving ideas are deeply embedded in the spiritual world of the Chinese nation and today it is still China’s basic philosophy in handling international relations.” Confucian thought defines peace in terms of self-restraint, rather than negotiation between competing interests.

Peace, in this sense, lies in “the avoidance of conflict,” with Chinese classics calling for the creation of incentives to form harmonious relationships, creating in turn a state of stability. This association of peace with stability, including the incentives and interests in maintaining this stability, is reflected in Xi’s frequent pairing of “peace” (和平), “stability” (稳定), and “progress” (进步). This conception diverges sharply from the liberal democratic concept of peace, which stresses negotiation, conflict resolution, and the protection of human rights. In other words, for Xi, peace is synonymous with stability and harmony – guaranteed by respect for authority, rather than compromise.

As reminded in the Concept Paper on the Global Governance Initiative, Beijing sees threats to peace and development as stemming from the “erosion of authoritativeness” and violation of international law as defined by the UN Charter. In Beijing’s usage, this invariably references Resolution 2758, which China (mis)interprets as legitimizing its claims over Taiwan. Peace with Chinese characteristics, therefore, entails enforcing Beijing’s interpretation of international law, centered on respect for the UN Charter (except its human rights provisions) and principles like sovereign equality and territorial integrity, as defined by Beijing.

China’s emphasis on the role of the UN, where every country’s voice is heard equally, directly relates to its effort over the past decade to pull it (partly through the BRI projects) closer to its worldview, at least on paper. According to the Economist, 70 countries have now officially endorsed China’s sovereignty over Taiwan and, just as crucially, its right to pursue “all” efforts toward “unification” – without specifying that such efforts should be peaceful.

Looking Ahead

The PLA will most likely continue showcasing China’s military superiority, conspicuously hinting at its plan to invade Taiwan with weaponry designed to counter Taiwan’s defenses and deter US intervention, while avoiding further warmongering or interventionist rhetoric. Similarly, although PLA leadership probably wishes for its troops to gain real combat experience, China’s approach to world conflicts is expected to remain low-risk and largely symbolic. Beijing will continue to foster the widest diplomatic cover possible to legitimize its own strategic interests.

The doves painted on China’s tanks are not mere decoration or cynical propaganda. As 2027 approaches, this dual messaging serves to prepare both international and domestic audiences for a potential reality: that Chinese control over Taiwan – achieved through force if necessary – could be framed not as aggression, but as the restoration of legitimate order. For Beijing, this would represent the ultimate expression of “peace with Chinese characteristics.”

Written by

Emma Belmonte

Emma Belmonte is China Projects Analyst at AMO, specializing in Beijing’s influence on European political discourse, Chinese security and law enforcement activities in Europe, and Taiwan-Europe cooperation. Emma has been working as a reporter specialized on Chinese speaking regions. She has conducted on the ground reporting in both Taiwan and China and written multiple feature articles for publications including GEO magazine, Figaro Magazine, Asialyst, the Green European Journal. She holds a Master’s degree in Modern Chinese Studies from the University of Oxford and a Bachelor’s degree in Philosophy from the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon.