Benign Invitations: China’s Playbook for Approaching Western Academics

This article is part of a newly launched section of CHOICE dedicated to in-depth investigations and personal insights that illuminate the lesser-known dimensions of Chinese influence in Central and Eastern Europe. In this space, we invite journalists, influencers, researchers, civil society actors, and others with first-hand experience to share stories that we believe decision-makers cannot afford to ignore. From covert media campaigns to subtle outreach tactics, this series shines a light on the informal tools and overlooked actors shaping perceptions of China in our region.

The message is always polite and flattering. A Chinese institution expresses interest in your work, often followed by a proposal for collaboration – generously funded but vaguely defined. Sometimes a specific project is mentioned; other times the language centers around “exploring synergies.” A CV or copies of academic degrees may be requested; later, perhaps, a scan of your passport. If you are a Western researcher, chances are you have received at least one of such unsolicited messages.

I’m Erika, and I lead the cybersecurity research team at the University Centre for Energy Efficient Buildings (UCEEB), part of the Czech Technical University in Prague. I normally delete these types of messages without a second thought, but a recent wave of outreach attempts has increasingly caught my attention. In this article, I share specific examples of these contacts, elaborating on how they were initiated and what I uncovered beneath the surface, to shed light on a form of Chinese academic outreach that often goes unnoticed.

An Inflection Point

China has spent the past decade refining its outreach to foreign universities, leveraging the very foundation of Western academia: openness. Until recently, many dismissed early warning signs, perceiving the outreach as largely innocuous. But in February 2025, Beijing released its Blueprint for Building a Strong Education System by 2035 – a state-backed roadmap aimed at reshaping global education governance in ways that reflect China’s national interests.

The Blueprint calls for enhancing the Study in China brand, improving visa and enrollment systems for foreign students, and boosting international exchange programs. Chinese universities are expected to lead or join major globally relevant scientific projects and build joint laboratories. Public-facing platforms such as the World Digital Education Alliance and massive open online courses (MOOCs) are expected to be utilized to shape the current governance model, with Chinese institutions encouraged to promote brands such as the Luban Workshop, which already operates in several countries as a Chinese-style vocational training model.

Western universities have already encountered this form of research outreach, seeing glimpses of where it can lead to. State-sponsored programs such as the Thousand Talents Plan have led to high-profile incidents involving undisclosed dual affiliations and technology transfers. Western researchers have participated in joint projects found to be linked to China’s military-civil fusion complex, and several Confucius Institutes were closed across Europe, North America, and Australia after investigations revealed interference in academic freedoms.

Now, Beijing is accelerating. Over the next three years alone, it plans to launch 800 international summer school projects and invite tens of thousands of Western students – including 50,000 from the United States and 10,000 from France – for exchange programs. Western academia is not only ill-prepared for dealing with such increase in China’s research outreach but, most of the time, it is unaware of the rationale behind these activities.

Example 1: A Proposal for Collaboration with a Chinese Defense University

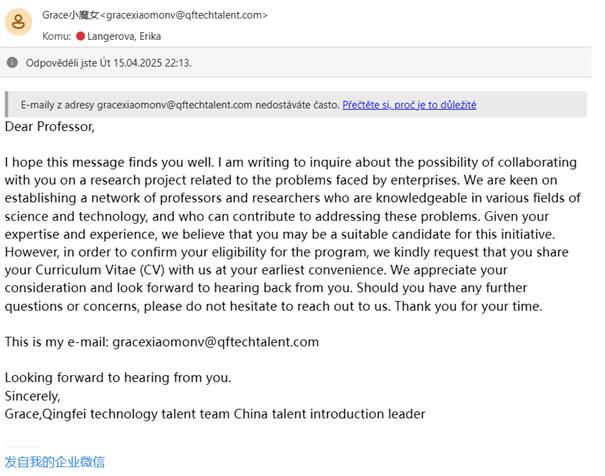

In January 2025, I received an email from “Grace,” a supposed representative of Jiangsu Qingfei Talent Technology. The invitation was to collaborate on a vaguely described “research project related to the problems faced by enterprises,” with a request for my CV and academic background documents. It looked unremarkable – like the kind of spam researchers routinely receive. But something about the email’s tone and timing prompted me to look closer.

The email from Jiangsu Qingfei Talent Technology

It quickly became clear that I was not alone – other researchers had received nearly identical messages in the past. A quick background check suggested that Grace was likely a bot, showing a particular interest in R&D related to strategic technologies like smart grids and lithium-ion batteries, as indicated by her LinkedIn profile. According to a Wikiversity entry, the Qingfei talent program offers up to ¥100 million (approximately $14 million) per project, with applicants asked to submit sensitive personal documents, including diplomas, passports, CVs, proof of employment, and records of previous projects.

But what stood out even more than the funding was the network behind the program. On its website, Qingfei openly lists affiliations with a number of high-risk Chinese universities that are involved in military and intelligence-linked research. According to the China Defense Universities Tracker, compiled by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), listed institutions such as Nanjing University, Zhejiang University, Tongji University, and the Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (NUAA) play a prominent role in China’s military-civil fusion – a strategy designed to integrate civilian research into the country’s defense objectives.

In this case, the risks were easy to identify as Qingfei publicly discloses its affiliations. But not all cases are as clear-cut. Similar initiatives can operate through intermediaries that obscure ties to military and intelligence-backed entities. This raises several broader questions: Are Western institutions adequately prepared to navigate this form of research outreach? Do individual researchers have the information and guidance needed to assess such proposals independently? And if not, do they know where to seek support in evaluating the legitimacy and potential risks involved?

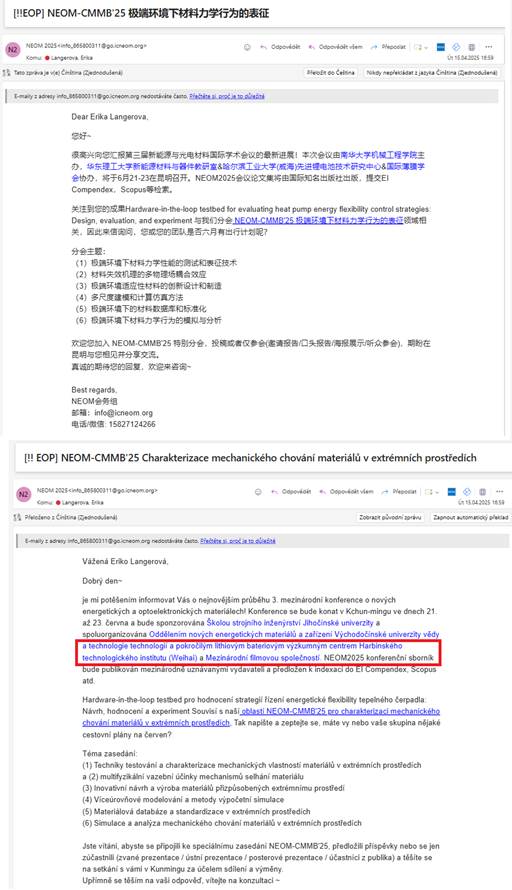

Example 2: An Invitation to a Conference Sponsored by Seven Sons

The second case I examined came just a few months later – in the form of a conference invitation. At first glance, the invitation to NEOM-CMMB’25 appeared to follow a standard academic format. A closer look, however, revealed that one of the co-organizers was the Advanced Lithium Battery Technology Research Center at the Harbin Institute of Technology(HIT) in Weihai – a satellite campus of a university classified as one of China’s Seven Sons of National Defense. These are institutions under direct state supervision and deeply embedded in the country’s military-civil fusion agenda. HIT’s involvement is particularly relevant in the context of lithium-ion battery technologies, which are not only strategic export products for China but also central to its push for technological self-sufficiency. China currently dominates the global market for lithium-ion battery energy storage systems (BESS), many of which are deployed in Western energy infrastructure.

A few weeks later, I received another invitation – this time to the International Symposium on IoT and Intelligent Robotics (IoTIR 2025). When I checked the conference website, I noticed that one of its listed sponsors was Central South University, an institution classified as high risk by ASPI due to its substantial involvement in defense research and close working relationship with China’s defense industry.

The invitation to the NEOM-CMMB’25 conference

The invitation to the IoTIR conference

This poses important questions: Would the average researcher recognize this as a red flag? Are Western researchers aware that some Chinese universities are deeply embedded in military programs? And do they understand the risks of sharing knowledge with such institutions, or even attending certain conferences?

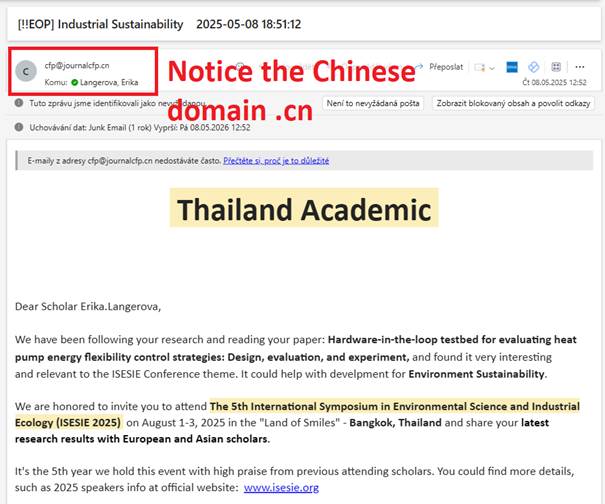

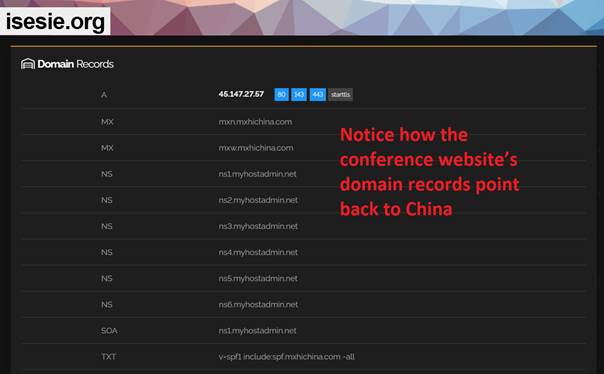

Example 3: Another Conference, but Outside China

Gradually, however, I started noticing a shift in the geographic location of these conferences. As Western intelligence agencies continued to issue warnings about the risks associated with traveling to China for academic events, Chinese organizers appeared to be adapting, mirroring a familiar strategy in business and technology, where Chinese companies facing export controls or reputational scrutiny operate through proxies registered in neutral jurisdictions such as Singapore. Indeed, while the conference invitations still came from Chinese domains, the conferences were now held in places like Singapore, Thailand or even Japan.

This highlights another critical point: it is not sufficient to ask where a conference is being held, researchers must also enquire about who is organizing it. Geography alone does not determine the level of risk; understanding the institutional affiliations behind the event is equally, if not more, important.

The invitation to a ISESIE 2025 conference in Thailand with a Chinese domain

Looking at the domain records of the ISESIE 2025 conference website, you can see that the trail leads to China.

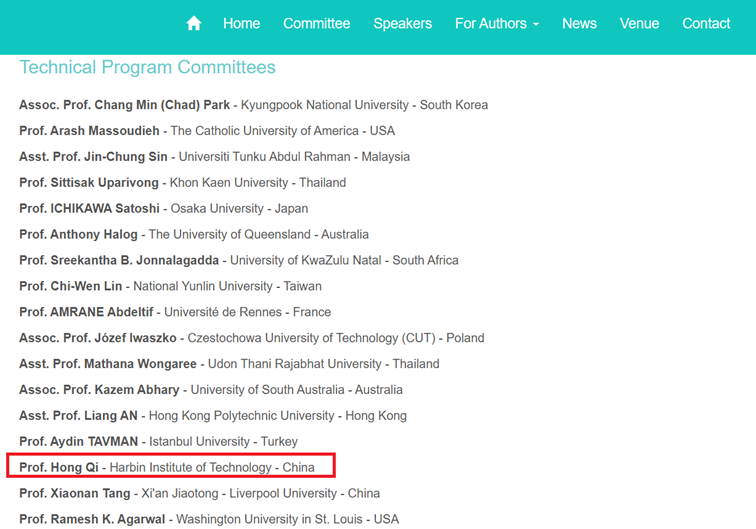

And looking at who’s on the ISESIE 2025 conference committee, you can see a lecturer from the Harbin Institute of Technology.

Another invitation, this time to a HEREM conference in Singapore

The HEREM conference website reveals that the event is sponsored by South China University of Technology and Shanghai Jiao Tong University, the former designated as medium risk and the latter as high risk by ASPI.

Example 4: A Shift to WhatsApp

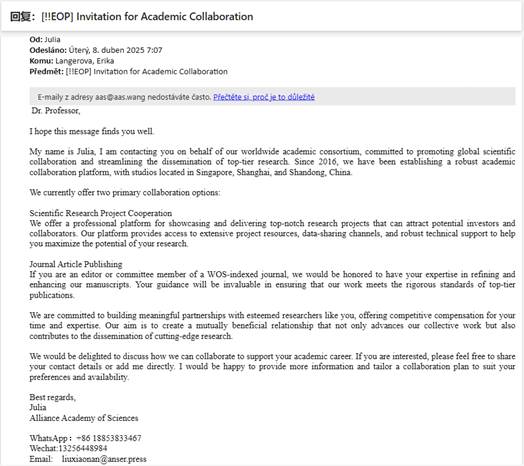

In early 2025, I received another email – this time from someone named “Julia,” representing an academic consortium. The message offered opportunities to co-author research papers and assistance with publishing, but was notably vague: it named no journals, listed no institutional affiliations, and provided no clear description of the work involved.

What stood out most, however, was Julia’s insistence on continuing the conversation via WhatsApp rather than through more official channels like email. This type of request seems to be increasingly common in unsolicited academic outreach. Shifting communication to encrypted apps such as WhatsApp or WeChat may reduce oversight, weaken institutional accountability, and limit traceability. If conversations venture into ethically or legally questionable areas, these platforms could potentially make it easier for senders to delete records or avoid attribution altogether. Such invitations may also serve as probes – testing whether a researcher might be open to more covert or sensitive collaboration in the future. As always, it is important to ask basic questions: Who is making the offer? What exactly are they requesting? And why are they trying to take the conversation off email?

The first email offering academic collaboration

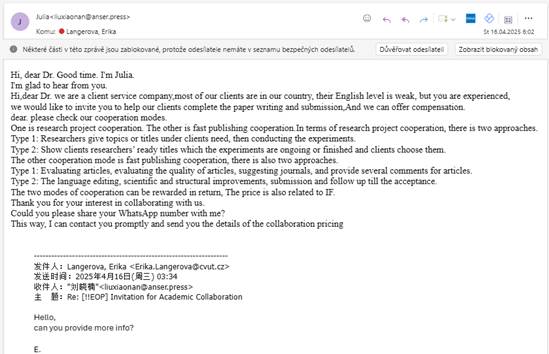

I replied requesting more information, as I was interested in seeing how the conversation would develop. You can clearly see the effort to move to WhatsApp at the end of the email.

Time to Build a Strategy for Academic Defense

What I’ve shared here is just a small glimpse into the types of unsolicited outreach researchers encounter daily, with the selected examples representing only a fraction of the messages circulating through academic inboxes worldwide. And yet, even this small sample reveals clear links to high-risk institutions.

If China’s 2035 Blueprint is any indication, we should expect a surge of new initiatives targeting Western academia. While some of these offers may appear benign – or even beneficial – they are increasingly part of a coordinated, state-driven strategy. Recognizing this must prompt a shift in how we respond. Academic institutions can no longer rely on assumptions of goodwill or presume that all international cooperation is harmless. What is needed is a clear, proactive strategy to safeguard academia and its researchers from malign foreign influence. Without such a framework, we risk leaving individual scholars – and the integrity of research itself – dangerously exposed.

Written by

Erika Langerová

Erika Langerová is the Head of Cybersecurity Research at CTU UCEEB. Her research focuses on securing distributed energy resources, with particular attention to the cyber warfare strategies of China and Russia and their implications for European energy infrastructure. She holds a Master’s degree in Engineering from the Czech Technical University in Prague and bases her work on years of hands-on experience as an analyst and software developer for energy resource control systems.