Germany’s Federal Election: Unpacking the Parties’ “Visions” for China Policy

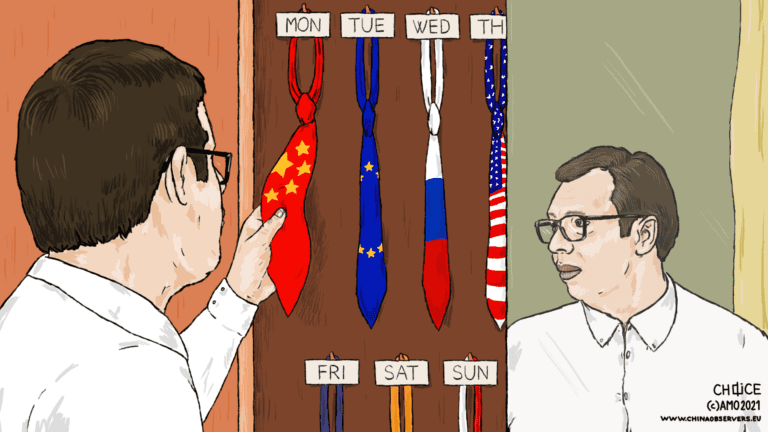

Germany’s upcoming federal election could mark a turning point for the country’s political landscape. A change of chancellor and the formation of a new governing coalition appear likely. While the parties expected to enter the next Bundestag largely agree that China has emerged as a strategic rival, they offer few concrete strategies for managing this rivalry considering Germany’s substantial economic interdependence with Beijing. Meanwhile, fringe political groups – opposed to Berlin’s foreign policy stance on China, Russia, Europe, and the United States – are gaining momentum. As a result, this election could serve as a preview of shifts to come in subsequent elections and shed light on how Berlin’s evolving approach to China may influence the European Union’s broader policy framework.

This article is part of a series from CHOICE focusing on the impact of elections on countries’ China policy.

Overall, references to China policy in electoral manifestos for German federal elections has steadily increased since the late 1990s. However, it seems that German political parties are paying slightly less attention to China compared to the 2021 election, likely due to more pressing issues such as the war in Ukraine. Notably, the Taiwan and Hong Kong issues, which featured prominently in 2021 manifestos, have almost vanished in 2025.

Mainstream Contenders

The center-right CDU/CSU, led by Friedrich Merz and polling around 30 percent, aims to retain strong economic ties with China where reciprocity is guaranteed, while minimizing critical dependencies through diversification and more rigorous screening of technology and infrastructure investments. On foreign policy, the party proposes to expand Germany’s Indo-Pacific presence, identifying China as a systemic rival and advocating for a dual approach that involves closer cooperation with the United States alongside a more assertive European stance.

The center-left SPD, headed by Chancellor Olaf Scholz and polling at about 15 percent – behind the CDU/CSU and the right-wing populist AfD – takes a more measured view. Calling China a “difficult partner,” the SPD nevertheless considers Beijing indispensable for addressing global challenges like climate change and nuclear nonproliferation. The party stands behind Germany’s first-ever China Strategy, advocates for a unified European position, and underscores the importance of open yet firm dialogue.

The Greens, previously part of the “traffic light” coalition (together with the SPD and FDP) under Economy Minister Robert Habeck, also poll just under 15 percent. They hold one of the most assertive positions on China, reflecting Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock’s values-based foreign policy. The Greens view China’s authoritarian model as a clear incentive for recalibrating Germany’s economic and security frameworks, urging reduced dependence on autocratic regimes, stronger supply chains, and tougher EU-level measures against unfair trade practices.

The liberal FDP, led by Christian Lindner, currently polls below the five-percent threshold required for Bundestag representation. Its departure from the government ended the “traffic light” collation. The FDP advocates “de-risking,” particularly in high-tech and security-relevant sectors, while preserving “as much trade as makes sense.” The party also distinguishes itself by championing deeper ties with Taiwan, pushing for a free-trade-like agreement at the European level.

New and Fringe Players

While the CDU/CSU, SPD, FDP, and Greens dominate mainstream German politics, newer parties have gained traction since the 2005 federal election. The right-wing populist AfD is now polling second, at around 20 percent. Led by Alice Weidel – an economist fluent in Mandarin who wrote her doctoral dissertation on China’s pension system – the AfD emphasizes Realpolitik over values-based diplomacy. The party sees China as a vital trading partner, criticizes its social credit system, and calls for an immediate end to development aid to Beijing.

The far-left Die Linke, hovering at around five percent, advocates diplomacy and opposes militarized engagement, especially in the Indo-Pacific. It argues that cooperation with China and other nations in the Global South is needed to resolve global conflicts like the war in Ukraine, diverging sharply from the mainstream consensus that calls for more robust deterrence.

A newly formed party, BSW, launched by former Die Linke leader Sahra Wagenknecht, is also polling near five percent. Economically left-wing but socially conservative, BSW favors diplomatic engagement with China, emphasizing its BRICS leadership and industrial capacity. At the same time, the party warns that Europe risks falling behind both the United States and China in digital and industrial development, advocating for pragmatic policies to prevent a harmful trade conflict.

The Road Ahead

Germany’s multi-party system, once dominated by two postwar heavyweights – the CDU and SPD – has become increasingly fragmented, with the CDU standing as the last major legacy party that still polls strongly. In the run-up to forming the next federal government, smaller parties like the FDP, Die Linke, or the BSW face the risk of falling below the Bundestag threshold, which complicates coalition arithmetic.

At this stage, the most likely governing arrangement involves the CDU leading a coalition, possibly with the SPD and/or the Greens. A CDU-SPD government would maintain much of the status quo, whereas a CDU-Greens alliance – already tested at the state level – could deliver moderate policy innovations without radically altering the fundamentals of Germany’s China policy.

A left-leaning coalition that includes the SPD, Greens, Die Linke, and even BSW is theoretically possible but would require bridging significant foreign-policy differences. Meanwhile, a right-leaning CDU-AfD coalition is difficult to imagine, given the CDU’s declared “firewall” against populist collaboration at the federal level – though local and regional developments suggest growing pressure for cooperation on issues like migration.

There is little clarity on how either a left-wing or right-wing bloc would handle Berlin’s relationship with China, particularly if the CDU and AfD were forced to reconcile the CDU’s traditional transatlantic focus with the AfD’s skepticism of the US-driven “anti-China” approach.

As Donald Trump returned to the White House, fringe positions on foreign policy – such as those held by the AfD, BSW, or Die Linke – might become more viable in Germany. Still, foreign affairs currently rank below domestic issues like the economy, social policy, and migration in voter priorities, making an abrupt shift in Germany’s China policy unlikely in the near term. Should Washington intensify its economic pressure on Europe, Berlin’s appetite for a tougher stance on Beijing could diminish as it tries to avoid economic retaliation.

All of this underscores a potentially complicated coalition-building process. Maybe Realpolitik should indeed play a pivotal role in the future of German China Policy – though not necessarily in the AfD’s mold. As international volatility continues to mount, the CDU and SPD must decide whether to stick to Germany’s transatlantic commitments under Trump or prioritize pursuing a more strategically autonomous Europe. Both paths involve trade-offs that could unsettle voters, from increased defense spending to restricted commercial ties. Should the balance tip further in favor of fringe parties like the AfD or BSW, it could leave behind the possibility of a unified European stance on China for good.

Written by

Tim Hildebrandt

Tim Hildebrandt is a Ph.D. candidate in political science and economics at the University of Duisburg-Essen and a Research Associate at the Ruhr West University of Applied Sciences. His research focuses on the intersection of politics, economics, and geography.