The political landscape in Serbia was upended on January 28, when Prime Minister Miloš Vučević announced his resignation, bringing an abrupt end to his government’s term. The resignation came nearly three months after student-led protests erupted across the country, demanding accountability for a disaster that claimed 15 lives – the collapse of the newly renovated railway station rooftop in Novi Sad.

The station’s modernization was a key component of a high-profile infrastructure project aimed at upgrading the railway link between Belgrade and Budapest, which has itself become a symbol of Serbia’s growing cooperation with China. Completed in the summer of 2024, the $1.5 billion project – funded through a loan agreement between the Serbian government, China’s Exim Bank, and the Russian government under the China-CEEC cooperation framework – was hailed as a milestone in regional connectivity.

It is thus not surprising that the collapse sent shockwaves through Serbian society, intensifying scrutiny of government oversight, foreign investment practices, and regulatory failures. Several government ministers resigned in the immediate aftermath, yet no comprehensive investigation or formal accountability process followed.

The Trajectory of Failure

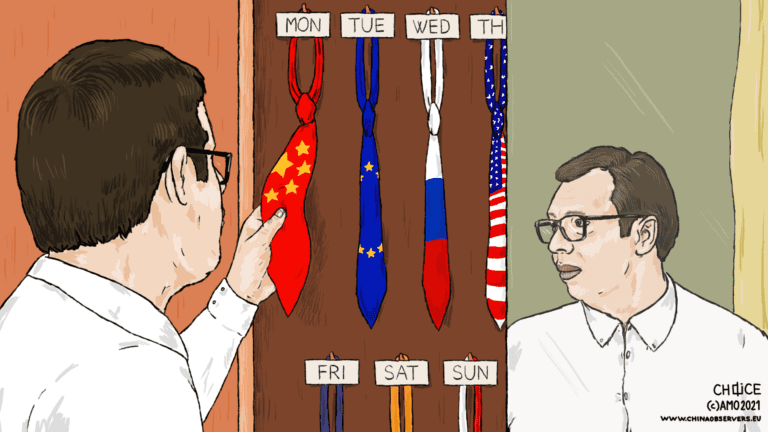

For many, the railway project had come to symbolize systemic issues of corruption, secrecy, and a lack of accountability. On February 1, in Novi Sad – the city where the tragedy struck – tens of thousands of people joined the rally, including students from Belgrade who marched 80 kilometers to stand in solidarity with their peers. As public backlash intensified, Serbian leaders, led by President Aleksandar Vučić, sought to contain the crisis by offering concessions to appease student protesters and their supporters. Yet, despite all this, a clear resolution remains elusive.

At the heart of the matter was the way the project was handled from the start. Critics argue that the collapse was not merely an accident but the consequence of a deeply flawed process in which public transparency was sidelined, international agreements were leveraged to bypass national regulations, and political interests were prioritized over safety. What’s more, in order to showcase progress, officials allegedly inaugurated the station before reconstruction work was complete.

The crisis has also provided an unprecedented look into the inner workings of Serbia’s infrastructure deals with China. From high-level government-to-government agreements to contracts between Chinese firms and local subcontractors, the controversy has exposed largely opaque processes. Thanks to relentless pressure from student protesters, key documents were finally made public, offering a rare opportunity for citizens to scrutinize a partnership that has long operated behind closed doors.

The railway project began as part of a broader agreement between Serbia and China on one hand, and China and Hungary on the other, with the shared goal of modernizing the railway connection between Belgrade and Budapest. Beneath the promises of faster, more efficient transport, however, laid deeper strategic interests – notably Beijing’s push to secure a reliable trade corridor from the Greek Port of Piraeus, a key entry point for Chinese goods into southeastern Europe. This interest only grew after the port’s management was taken over by the Chinese shipping giant COSCO.

On Serbia’s end, the railway modernization was divided into three sections. The first two sections were financed through Chinese loans and constructed by Chinese firms, with the final section awarded to Russia’s state railway company under a similar loan-based financing model. What was framed as an ambitious infrastructure upgrade thus soon became a case study of how foreign-backed projects operate in Serbia, including the opaque terms that often accompany them.

International agreements signed between the Serbian government and China’s Exim Bank in May 2017 and April 2019 revealed that the modernization of two key railway sections was awarded to a Chinese consortium consisting of China Railway International and China Communications Construction Company. These agreements, adopted by the Serbian parliament, were publicly available. What remained inaccessible, however, were the commercial contracts between Serbian authorities – including the Ministry of Construction and Serbian Railways – and the Chinese consortium. One such agreement, covering the section that included the Novi Sad railway station, was signed in July 2018, revealing a critical detail: the selection of Chinese firms for the project was predetermined before the loan agreements were finalized.

Construction on the Novi Sad-Subotica section of the railway began in 2021, with a planned completion date set for the end of 2025. In a high-profile event on October 3, 2024, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić took a test ride along the route, proudly announcing that the project would be completed a full year ahead of schedule. He also toured the newly renovated Subotica station, touting the modernization effort as a major success.

As of February 2025, however, the railway from Novi Sad to Subotica remains non-operational, and the government now finds itself under intense scrutiny following the tragic collapse of the Novi Sad station. With public trust shaken and officials struggling to control the fallout, the timeline for inaugurating the final segment of Serbia’s railway project remains uncertain.

Facilitating Disaster: The Role of Chinese Companies

Chinese companies played a critical role in the modernization project, yet they have largely escaped the level of scrutiny faced by domestic actors. Public outrage over the Novi Sad station collapse was overwhelmingly directed at the Serbian government and its officials. Many saw domestic actors as the primary culprits, accusing them of implementing a project riddled with secrecy and mismanagement. Protesters demanded the publication of all project-related documents, accountability for those responsible, and a transparent investigation – especially after government officials issued conflicting statements, even attempting to downplay the incident by claiming that no work had been done on the station’s rooftop. But as public pressure intensified, nearly 800 documents were released, shedding new light on the project’s many layers.

Another factor shielding Chinese companies from intense scrutiny was the swift placement of blame on a Serbian subcontractor, Starting, a company hired by the Chinese consortium to renovate the Novi Sad rooftop. According to Forbes Srbija, the Chinese firms explicitly stated in a letter from November 3, 2021, that Starting was responsible for the renovation. Indeed, Serbian government officials later confirmed that the Railway Infrastructure of Serbia – the state entity overseeing the project – had approved Starting as the subcontractor.

Yet a crucial question remains: To what extent were the Chinese companies involved in the actual construction? With reports indicating that between 90 and 130 subcontractors were hired for the project, the full picture of who was truly responsible for the station’s faulty reconstruction remains murky. As Serbia’s political crisis deepens – with no new government in sight – student protests continue to gain momentum, rallying around broader issues of corruption, transparency, and accountability. And while domestic officials remain the primary focus of public outrage, a pressing question lingers: Who enabled the practices that ultimately led to the deaths of 15 people?

Prevention or Repetition?

For years, Serbian leaders have championed cooperation with China as a pillar of the country’s economic and infrastructure development. The partnership has often been framed as “no-strings-attached” – a model where Chinese investment flows without the pressures of regulatory oversight or strict compliance with international standards. But the tragedy in Novi Sad underscores a dangerous flaw in this approach. When accountability is absent and safeguards are ignored, the consequences can be catastrophic, putting human lives at stake.

To prevent further disasters, Serbia must rethink its approach to foreign-backed projects. Transparency, legality, and accountability must become non-negotiable principles, regardless of the partner involved. This means ensuring that all agreements – whether with China or any other foreign investor – are subject to public scrutiny, adhere to the highest safety and labor standards, and uphold the rule of law. Only through such reforms can Serbia rebuild public trust and prevent similar tragedies in the future.

Written by

Stefan Vladisavljev

vladisavljev_sStefan Vladisavljev is CHOICE Visiting Fellow. He is also the Program Coordinator of the Serbia-based non-governmental organization Foundation BFPE for a Responsible Society. He analyzes Chinese presence in Central and Eastern Europe with a special focus on Serbia and the Western Balkans.