Xi Jinping’s Ideology in the Age of AI and What It Means for Chinese Foreign Policy

In today’s China, ideology no longer marches through the streets. It slips seamlessly into citizens’ daily lives through algorithms, mobile apps, and AI-powered technologies. What began as Mao Zedong’s revolution of slogans and little red books has evolved into Xi Jinping’s quiet system of constant ideological reinforcement. The consequences of this shift may influence China’s foreign policy – especially regarding Taiwan – and extend far beyond its borders.

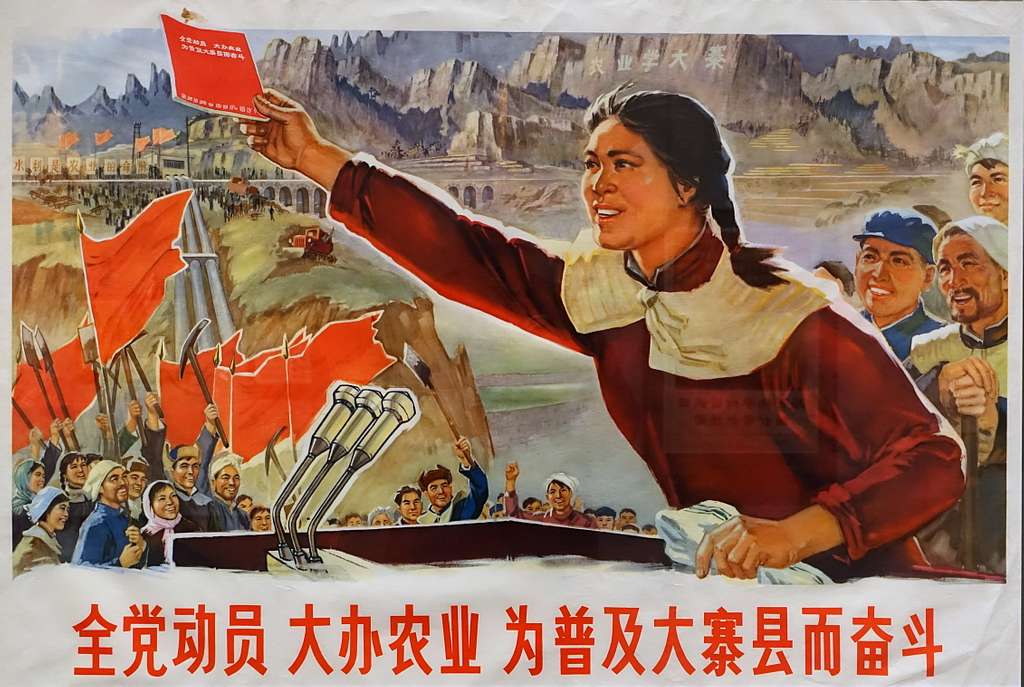

In Mao Zedong’s China (1949-1976), ideological enforcement came in the form of a pocket-sized booklet called “Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung,” commonly known as the Little Red Book. It was not merely a symbol of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) but a (literal) tool of survival for many Chinese, and a sign of submission to Mao’s regime. Carrying it, quoting it, and living by its doctrine was often the only way to remain safe amid the Red Guards’ violence and political purges.

Nearly sixty years later, after decades of more pragmatic economic development, Xi Jinping is orchestrating a sharp return to omnipresent ideology – and is doing so using the most up-to-date tools available. Moreover, the evolution of ideological enforcement in China mirrors the country’s broader shift from an underdeveloped, rural nation to a futuristic, hyperconnected society in which technology is an indispensable element of daily life – much more so than in any Western society.

From Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book to Xi Jinping’s Algorithmic Indoctrination

Mao’s indoctrination was designed as a violent spectacle. The Red Guards, public shaming, self-denunciation sessions, and an omnipresent cult of personality made ideology loud, visible, and unavoidable. After Mao’s death, Deng Xiaoping shifted the country’s focus to economic modernization, relegating ideology to the sidelines. This approach defined China’s policies for decades and changed only with Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012.

Xi reintroduced ideology at the core of political life, albeit in new forms. For instance, in 2019, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched a mobile app called “Xuexi Qiangguo” (学习强国). Its name literally translates to “Study the Great Nation,” but it also plays on the word “study” or “xuexi” (学习) and Xi Jinping’s name (习近平), allowing for the interpretation “Study Xi’s Strong Nation.” The app’s logo uses the same calligraphy of the word “study” found in Mao’s famous slogan “Study Well and Make Progress Every Day” (好好学习,天天向上), effectively symbolizing Xi’s claim to continue Mao’s ideological legacy.

Although voluntary on the surface, the app is strongly encouraged – sometimes even required – in numerous workplaces, schools, and universities. For the first time in China’s history, the official ideology has become quantifiable and measurable at scale.

But Xi and the Party are not stopping there. In 2024, the authorities announced the development of an AI-powered large language model trained on Xi Jinping’s Thought. Once released to the public, it is expected to be used in schools, Party trainings, and perhaps even daily activities. By providing answers based on the official ideology, the model could become an AI-powered echo chamber, designed to quietly normalize Party doctrine, and deepen conformity across Chinese society.

The Taiwan Question

But why does this matter for Chinese foreign policy? Because the CCP’s intention to use AI to shape beliefs and values is not simply domestic political theater – it is part of cultivating a deeply ideological nationalism that could harden Chinese attitudes toward compromise, especially on sensitive issues like Taiwan.

Taiwan has always been central to the CCP’s narratives regarding national reunification and historical redemption. However, under Xi Jinping, it has been reframed as the absolute core element of China’s “great rejuvenation,” which is intended to be completed by 2049. In this context, AI-powered technologies could be employed by the Party to help entrench the view that Taiwan’s return is inevitable, non-negotiable, and essential to reclaim China’s “rightful” place as a global superpower. To date, the CCP has promoted these ideas without openly rallying public support for military confrontation.

Yetgiven the Party’s near-total control of digital infrastructure and algorithmic tools that shape public discourse, these narratives could shift swiftly and dramatically, becoming more antagonistic or even overtly confrontational should political circumstances demand it.

Here lies the geopolitical risk: in a society where obedience is rewarded, dissent is filtered out, and Party narratives are woven into citizens’ daily lives, this kind of ideological indoctrination may not feel imposed. It may feel natural. Over time, AI-powered normalization of increasingly confrontational attitudes – for example, toward Taiwan – could foster a public not only receptive to hardline policies but psychologically primed to support them if diplomatic solutions fall short.

Beyond the Rational Actor?

What further makes China’s algorithmic indoctrination especially consequential is its potential to redefine the understanding of the Party-state’s behavior, especially among Western observers. Traditionally, analysts assessed China’s intentions through rational indicators such as economic growth, the scale of its military buildup, and the contents of its official discourse. But if public sentiment is continuously reshaped and seamlessly encoded in everyday lives by AI-driven ideological reinforcement, those indicators may become less reliable.

In other words, China can become significantly less predictable. As ideological pressure mounts and digital echo chambers potentially normalize confrontational thinking, the rational calculus long relied upon by Western analysts could erode.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine offers a sobering precedent. Before February 24, 2022, numerous Western experts dismissed the possibility as too irrational, predicting Russia’s attack would be economically ruinous, socially destabilizing, and diplomatically isolating. And yet it happened. A state operating within its own ideological bubble, with few internal checks on power structures and narratives, can act in ways that appear irrational to outsiders, but feel entirely justified from within.

Looking Ahead

Whether China will follow a similar path vis-à-vis Taiwan remains to be seen. However, in a system where beliefs and sentiments are algorithmically engineered and dissent is filtered out, it would be a mistake to assume Beijing will always act according to conventional notions of logic, strategy, or rationality. The world must prepare for a scenario in which ideology – not traditional cost-benefit analysis – drives decision-making, and in which the next geopolitical shock emerges from a leadership emboldened by its own echo chamber – one that has been digitally engineered, algorithmically reinforced, and sustained by an indoctrinated population.

Written by

Konrad Szatters

Konrad Szatters is a China Analyst at AMO, focusing on China’s political discourse and foreign policy. He also serves as a Lead Researcher for the Ukrainian Heritage Diplomacy in China at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand. Previously, he gained experience at the College of Europe in Natolin, the Polish Diplomatic Academy, and the Embassy of Poland in Beijing.