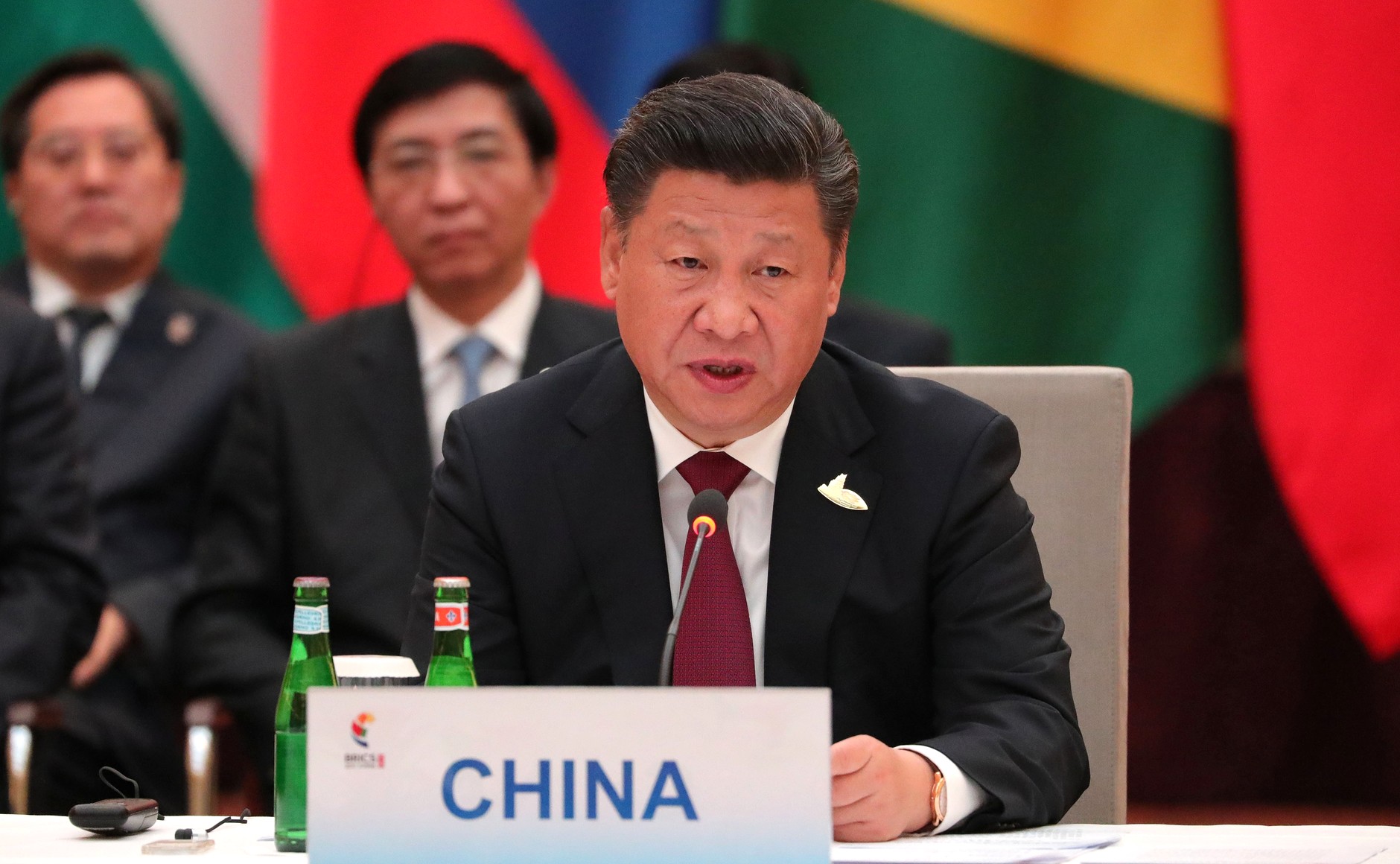

In 2023, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) convened a large online gathering of political parties. This virtual call of leaders posed a bigger challenge to Europe than its looks suggested. During his keynote address, Xi Jinping launched the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI). This collection of seemingly harmless platitudes matters – not because of its political persuasiveness, but because it caps Beijing’s ongoing expansion of tools to influence politicians worldwide.

The GCI consolidates a range of tools Beijing uses to shape the international environment by targeting individuals, thereby complementing state-centered tools such as the Belt and Road Initiative. In comparison to the long-standing influence of American and European education systems and soft power, GCI’s vague statements about “mutual learning between civilizations” appear benign. The initiative, however, is linked to a broader project exporting China’s party-state governance model. The GCI now gains traction in Eastern Europe from Serbia to Hungary. This is problematic as over time it could erode national sovereignty from within, especially when crises arise.

Xi’s Trilogy of Initiatives

Debates about the CCP’s vision for world order often focus on whether Beijing has a coherent, universalist project. This framing, however, misunderstands what ideology means in the People’s Republic of China. In China’s Leninist party-state, political concepts are not just abstract doctrines but instruments for steering concrete actions. The GCI is the third in Xi’s series of now four global initiatives designed to manage different aspects of the international system.

Each initiative functions as a capstone that integrates earlier projects. The Global Development Initiative (GDI), announced in 2021, brought together economic schemes from 2013 onwards, most notably the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which, in turn, built on projects by previous Chinese leaders. The Global Security Initiative (GSI), launched in 2022, combined Beijing’s domestic and international security offerings. The Global Governance Initiative (GGI), launched in 2025, reflects years of Chinese engagement in the multilateral arena. Expanding this logic into the political arena, the GCI serves as an umbrella initiative targeting both political elites and civil society representatives.

The Leninist Leash

China’s external operations reflect its Leninist political system. The CCP governs through what has been called an “organizational weapon” – i.e., the party state, which itself operates through two steps: organization and mobilization.

Organization involves creating structures that can control different spheres of Chinese society. Party secretaries dominate the state and economy, political commissars oversee the armed forces, the United Front manages and supervises community groups, and security agencies have operatives engaged in both overt and covert activities. All these control threads ultimately come together in the hands of the General Secretary. Elsewhere, I have described this system as the “Leninist Leash.”

Once in place, the Leninist Leash is used for mobilization. Rather than relying on rigid laws and exhaustive policy plans, which stifled the Soviet Union, the central government in Beijing relies on campaign-style governance. Slogans and speeches cascade down the leash, signaling policy priorities. Subordinate bodies then rush – relatively independently – to implement them, incentivized by disciplinary inspections, quantitative evaluations, and competition with each other.

While this system cannot be replicated abroad, similar effects are visible in what some have called Beijing’s “sharp power.” Economic ties and development aid are used to punish misbehaving countries like Lithuania while rewarding friends like Hungary. In the security arena, police cooperation with the Solomon Islands and Beijing’s shared worldview with Russia further illustrate this logic, with the GCI being a logical next step that extends such behavior management to individual elites.

GCI in Action

The GCI’s announcement capped a period of expanding activities, consistent with the CCP’s practice of developing policy frameworks by starting with smaller steps on the ground. While multiple bureaucracies are involved, the International Department of the Communist Party of China (IDCPC) plays a leading role. Originally responsible for CCP ties with fellow communist parties, its remit has, since the Cold War, expanded into broader party-to-party diplomacy. Here, we can see three kinds of approaches to organization:

- 1. Structured party exchanges: The IDCPC regularly meets with foreign politicians. In Europe, the most institutionalized are the regular dialogues with Germany’s major parties. Until his recent disappearance, the head of the International Department Liu Jianchao was more visible abroad than his predecessors. These exchanges also involve semi-official think tanks, such as Hungary’s government-linked Mathias Corvinus Collegium.

- 2. Training of foreign officials: The IDCPC is also involved in training foreign officials, as seen in the increasing number of briefing delegations sent abroad to explain Chinese policies. A prominent example is the Nyerere Leadership School in Tanzania, which, backed by the CCP’s Central Party School, promotes Chinese political ‘solutions.’

- 3. Large-scale summits: Beijing hosts large international summits, regional forums, and headline events such as the Communist Party of China in Dialogue with Political Parties of Central and Eastern European Countries. Larger summits like the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) or the China-CEEC Forum combine elements of GDI, GSI, and GCI.

World leaders have clear practical reasons for pursuing dialogue and exchange with countries as powerful as China. Yet, the organization structures created through these types of interactions enable internal mobilization that can undermine national sovereignty in three ways:

- 1. Influence campaigns: Structured exchanges with political parties and think tanks not only provide Beijing with channels to promote its values. They are also used for coordinated influence campaigns. Organizations controlled by the United Front Work Department or the Ministry of State Security can use these opportunities to identify agreeable individuals who may be useful in the future. The dialogues also provide leverage in themselves, as Beijing is known for threatening cancellation in response to ‘bad’ behavior.

- 2. Elite capture and grooming: Briefings, leadership academies, and scholarships promote CCP governance models, instilling values in promising early-career individuals while identifying useful figures for long-term cultivation.

- 3. Summit incentives: Participation in large-scale summits and high-level meetings is itself a powerful incentive for foreign leaders, as they offer prestige and access to senior Chinese officials. Exposure to such settings makes it more likely that participants internalize Beijing-approved values, with the gatherings further reinforcing networks among like-minded politicians.

The outcomes of these mobilization efforts are then twofold. Not only do they allow Beijing to shape the views of current and future political elites but also to influence who counts as an elite in the first place.

Correct Politics

Whereas GDI and GSI target states with concrete incentives, the GCI operates within the body politic to target elites. It enforces a ‘correct’ way of discussing political differences between states, with Beijing monitoring closely for ‘incorrect’ statements. Those who ‘misspeak’ risk immediate condemnation. Mobilization efforts also create material incentives. Domestically, access to Beijing can boost one’s political career; internationally, deviation invites political or economic punishment from China and peer states.

The result is a growing cadre of global political elites always mindful not to cross Beijing’s red lines – and at times even actively advancing them. Afterall, human beings are social creatures whose views are shaped by what is socially acceptable around them. Social forces reinforce this behavior: those who remain silent feel isolated, while the incentive of a conditional access to Beijing makes compliance appear rational and safe, creating a collective action problem.

Especially along its eastern and southern peripheries, the European Union faces increasing competition with GCI for elite attention. The initiative’s legitimizing of specific Chinese values while undermining Western liberal-democratic norms is only half the problem. While GCI’s structures may ease and facilitate the spread of anti-Western narratives, its real power lies in mobilization, ensuring greater compliance with Beijing’s interests.

Written by

Sense Hofstede

sehofDr Sense Hofstede is an expert in the influence of the Chinese party-state on Beijing’s foreign policy, cross-Strait politics, and the international relations of the Indo-Pacific. He has completed his PhD in Comparative Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore and has previously worked as a Lecturer at Leiden University and a Research Fellow at the Clingendael Institute.