On January 3, 2026, the US forces carried out a dramatic operation in Venezuela, seizing President Nicolás Maduro and his wife and extraditing them to stand trial in New York. The following day, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić convened an emergency session of the National Security Council. Addressing the nation afterward, Vučić framed the incident as proof that “the old world order is collapsing,” declaring that the “international public law and the United Nations Charter no longer function,” and that global affairs are now ruled by “the law of force” and “the right of the stronger.”

Venezuela’s Shockwave Reaches Belgrade

In reaction to the US operation in Venezuela, President Vučić also announced a sweeping plan to bolster national defense, calling for massive military investments, large-scale weapons procurement, and the reinstatement of mandatory conscription to deter potential security threats in the region. This move, the Serbian President argued, was necessary to make Serbia safe in a dangerous new world.

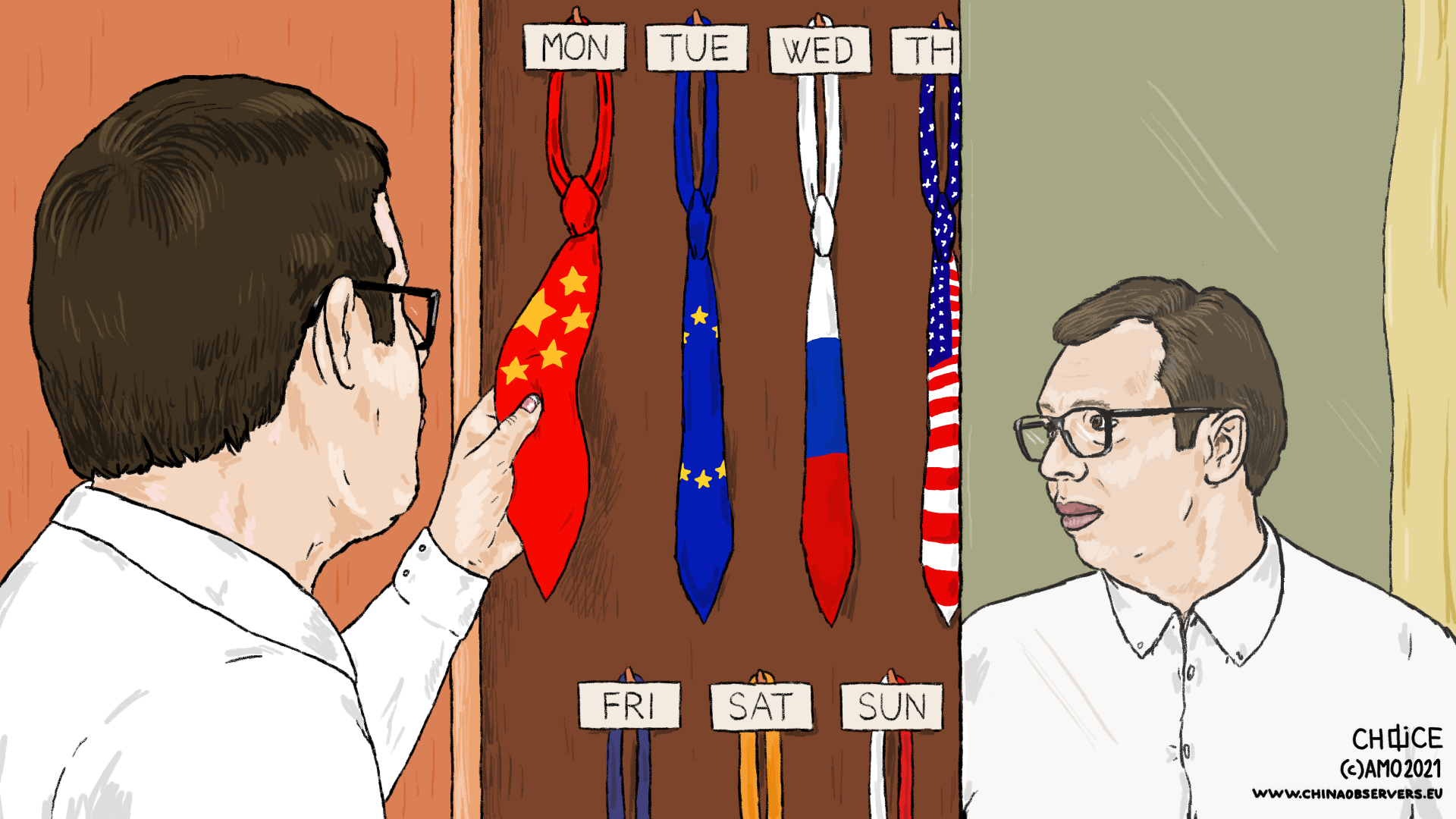

However, Vučić’s call to arms runs into a stark and inconvenient geopolitical reality. For Serbia, the pursuit of such an ambitious military overhaul collides directly with the profound erosion of its longstanding foreign policy framework: the delicate balancing act between Brussels, Washington, Moscow, and Beijing. Most of these traditional “pillars” are now unstable: relations with the EU are at a historic low; Washington is preoccupied with the Trump administration’s America-first priorities; and the partnership with Moscow has been strained by the war in Ukraine, disputes over the Russian energy giant Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS), as well as Serbian weapons shipments to Kyiv. In this climate of strategic isolation, where can a small, self-declared neutral state turn to rapidly modernize its armed forces?

This convergence of necessity and opportunity makes a substantial upgrade of the Serbia-China security relationship the most viable path forward. By solidifying China as a cornerstone of its military modernization, Belgrade would not merely be “diversifying suppliers” as official rhetoric likes to point out. It would be actively reinforcing a strategic corridor for Chinese influence in the heart of Southeast Europe, as well as contributing to the destabilization of regional security in the Balkans.

The Crumbling Foreign Policy Pillars

For over a decade and a half, the guiding doctrine of Serbian foreign policy has been the “four pillars” approach. Articulated by the former President Boris Tadić in 2009, this principle holds that Serbia’s national interest is best served by cultivating balanced, strategic relations with the EU, the US, Russia, and China simultaneously. Although the “four pillars” policy always maintained that its ultimate strategic goal remains Serbia’s EU membership, the other pillars were designed to ensure Belgrade retains sovereignty, extracts economic benefits from all sides, and avoids over-dependence on any single power center. This doctrine has remained central to the Serbian foreign policy establishment to this day.

However, the strategic landscape that made this balancing act possible before is now deeply fractured. Beginning with the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the ensuing re-polarization of global politics, the “four pillars” doctrine became increasingly costly to sustain. In a world of hardening geopolitical blocs, the major powers began to demand clear alignment and to view neutrality with suspicion rather than understanding.

How 2025 Fractured Serbia’s Foreign Policy Doctrine

Building on this trend, the events of 2025 delivered a synchronized shock to Serbia’s foreign policy doctrine. Washington, through the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions against the Russian-owned NIS energy giant, sent an unambiguous message to Belgrade: no geopolitical special treatment is possible and any alignment with Russia comes at a direct and severe cost. This situation then led some influential voices within Serbia’s ruling party to publicly call for nationalization of NIS, while accusing Russia of abandoning Serbian interests for selfish gains.

Hence, the Serbia-Russia relationship, which was already deeply strained by Kremlin intelligence revealing nearly a billion dollars in Serbian arms sales to Ukraine, soured to its lowest point in decades. Simultaneously, the EU-Serbia relations reached a new low, driven by Serbia’s continued refusal to adopt EU sanctions against Russia and Brussels’ criticism of Belgrade’s response to the ongoing anti-corruption protests. This deterioration was starkly illustrated on January 13, 2026, when President Aleksandar Vučić declined to meet with a visiting EU delegation, publicly labeling its members as “haters of Serbia”. In yet another unambiguous signal, no official Serbian representative attended the 2025 EU–Western Balkans Summit, the first such absence in the forum’s history.

When contextualized, President Vučić’s historic rearmament announcement points to China as the necessary, if not the only large-scale partner for his military modernization ambitions. As relations with Washington, Moscow, and Brussels remain strained or complex, Belgrade sees Beijing as the last remaining “pillar” of Serbia’s foreign policy that is still willing and capable to source advanced weaponry and offer strategic alignment. This geopolitical reality now seems to be the primary driver behind Belgrade’s urgent push to formalize and accelerate a deepened security partnership with China.

China’s Established Military Foothold in Serbia

Although the current geopolitical crisis is accelerating certain events, the strategic alignment between Serbia and China in the defense sector is the result of years of steady momentum. This is reflected in clear procurement trends. According to the data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), from 2020 to 2024, China supplied 57 percent of Serbia’s major arms imports, solidifying its position as Belgrade’s dominant supplier ahead of Russia (20 percent) and France (7.4 percent). Serbia’s current pivot, therefore, is not a new direction. It represents a significant and likely rapid intensification of a pre-existing, deeply established partnership, one that current circumstances are poised to advance decisively.

This reliance is both concrete and pioneering. Serbia has strategically positioned itself as China’s primary military partner in Europe, becoming the first country on the continent to deploy key Chinese systems like the CH-92 and CH-95 armed drones and the FK-3 and HQ-17 surface-to-air missile batteries.

In 2025, the growing partnership extended beyond hardware, embedding itself into military doctrine and personnel. In a clear signal of deepening institutional trust, a Serbian special operations brigade completed its first-ever joint training with a Chinese counterpart in Hebei Province in July 2025. Conducted despite strong objections from the EU and NATO, the exercise, dubbed “Peacekeeper 2025,” focused on drone tactics and interoperability in mixed combat teams. This evolution from defense procurement to joint tactical exercises signifies the natural maturation of a partnership that has for years been deliberately cultivated to form the cornerstone of Serbia’s future defense posture.

New Variable for Balkans and CEE Regional Security

The decisive acceleration of Serbia’s military partnership with China should be understood within its immediate regional security context: a spiral of heightened threat perception between Belgrade, Priština, and Zagreb.

This perception is not merely inferred. It is the explicit, public rationale offered by Belgrade’s leadership. During a highly symbolic visit to Beijing on September 3, 2025, President Aleksandar Vučić informed the media that his attendance at the Chinese military parade was, among other things, used to assess “what might be interesting to acquire for the needs of the Serbian Army, so that it could serve as a deterrent factor against any potential aggressor from the neighborhood.” He directly linked this procurement logic to recent regional alignments, asserting: “it is no coincidence that Priština, Zagreb, and Tirana have formed a military alliance. And they did not form it because of Austria, Hungary, or Slovenia, but because of Serbia. They formed it against Serbia.”

President Vučić reiterated this strategic rationale during his national address on the US operation in Venezuela. Having framed Maduro’s capture as a cautionary lesson for Serbia’s sovereignty, he pointed directly to the “accelerated arming of Priština,” declaring that “a particular threat to territorial integrity is the alliance of Priština, Tirana, and Zagreb,” which he said now spans “the joint development of complex combat systems.”

This accelerating trend risks locking the Western Balkans into a destabilizing action-reaction cycle precisely when the broader transatlantic security architecture is under unprecedented strain. With the institutional foundations of the EU and NATO facing profound tests due to, among other factors, Trump administration’s destabilizing maneuvers regarding Greenland, the EU cannot afford a parallel crisis fueled by advanced weapons transfers and escalating threat perceptions.

European leaders must therefore monitor this Sino-Serbian security corridor with exceptional diligence, not merely as a bilateral concern, but as a potential catalyst for regional instability. For the EU, the task is no longer to question if Belgrade will deepen its military dependence on Beijing, but to prepare for the consequences, and do whatever it takes to ensure that the Balkans does not become the next theater where great-power rivalry ignites local conflicts.

Written by

Stanislav Knezevic

Stanislav Knezevic is a China Analyst specializing in Chinese foreign policy, media influence, and engagement in Central and Eastern Europe, particularly the Western Balkans. He holds an MA in Politics and International Relations from Yenching Academy, Peking University, and a BA in Political Science from Trinity College. He built his professional expertise through appointments at UNDP, the Serbian Embassy in China, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.