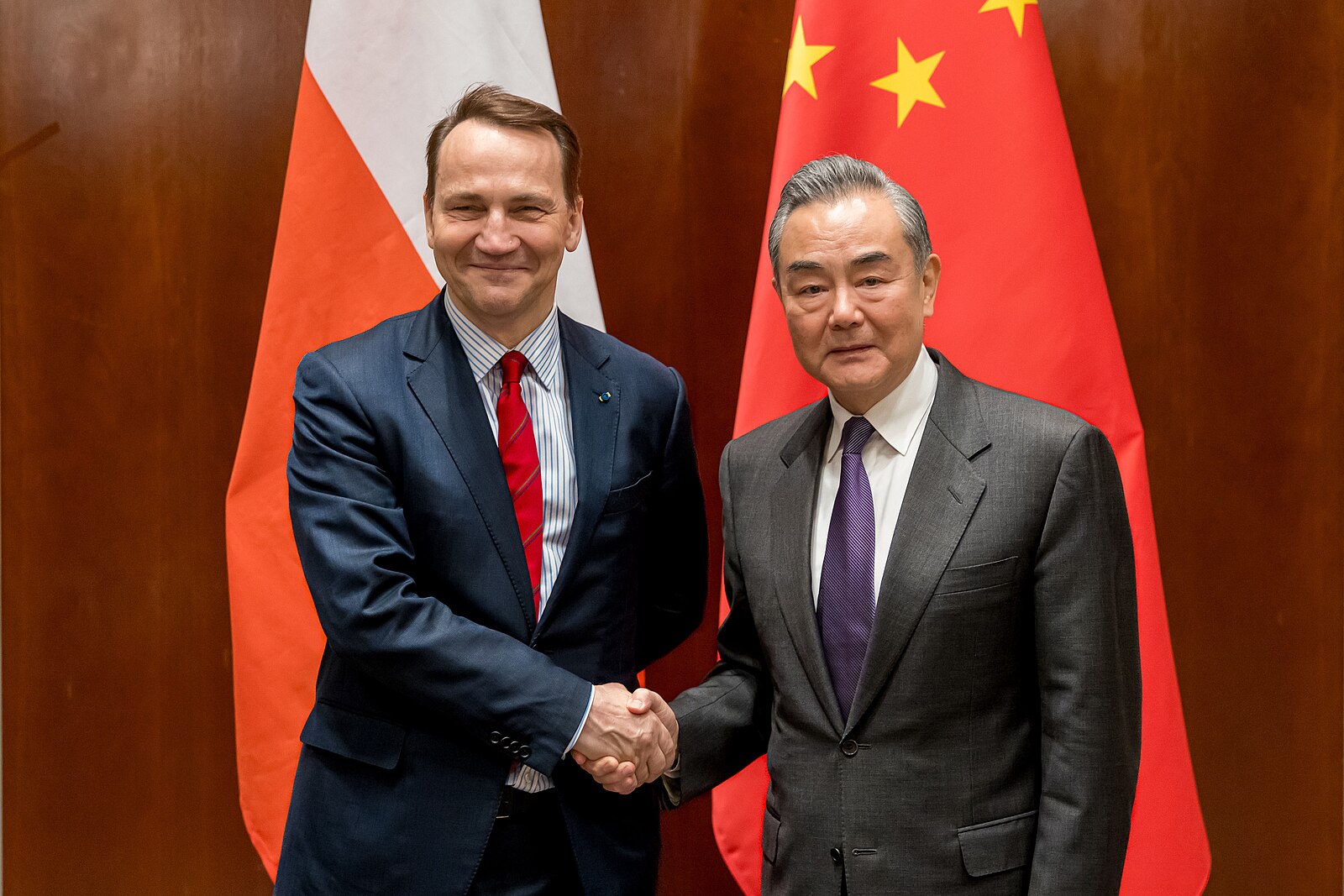

On September 15, Poland witnessed its first visit from a Chinese foreign minister in six years. As part of a broader European itinerary that also included Slovenia and Austria, Wang Yi’s stop in Warsaw featured the fourth meeting of the Poland-China Intergovernmental Committee and a dialogue with recently inaugurated President Karol Nawrocki. Although the two sides did not issue a joint statement, separate press releases highlighted a wide spectrum of topics discussed between Wang and his Polish counterparts: from market access for Polish poultry to the security of Eurasian logistical corridors, and from the Russian war in Ukraine to Beijing’s claims over Taiwan.

The visit was more than a mere courtesy call. It offered a timely opportunity to assess the state of Poland-China relations at a time of multi-level change: upheaval in transatlantic ties, growing Russian belligerence toward NATO, the consolidation of an anti-Western bloc with Beijing at its helm, and the domestic context of Nawrocki’s rise to the presidency. Yet, as the visit made clear, Warsaw and Beijing remain fundamentally out of sync in interpreting the implications of these global security shifts – especially regarding Russia’s aggression and the future of European security. This disconnect was especially visible when the dialogue turned to geopolitical flashpoints on NATO’s eastern flank.

Confronting the “Decisive Enabler”: A Dialogue of the Deaf

Just days before Wang’s arrival, Russian drones penetrated Polish airspace. This marked an unprecedented challenge for NATO, triggering allied intercepts and Article 4 consultations. As Wang’s trip had long been on the calendar, it would be unsubstantiated to see it as a direct response to Moscow. Yet, the incident raised the stakes for any Warsaw-Beijing exchange. In addition to this, Beijing’s recent WWII ceremonies – attended by Russia, North Korea, Iran, and Belarus – signaled deeper alignment among anti-Western actors and China’s ambition to reshape global rules, further limiting the scope for meaningful growth in Poland-China relations.

Unsurprisingly, Russian aggression against NATO’s eastern flank featured prominently in Wang’s meetings with both foreign minister Radosław Sikorski and president Nawrocki. Yet both sides interpreted these dynamics differently. Beijing’s interpretation was generic and “equidistant”: it avoided naming Russia, called for “peace talks,” and cast China as a facilitator of a future European security architecture. Poland’s position was more concrete and unequivocal: grounded in the UN Charter, it stressed Ukraine’s sovereignty, explicitly blamed Russia, and cited drone incursions into Polish airspace as deliberate provocations. Both sides referenced de-escalation, but while Poland emphasized deterrence and accountability, China stressed dialogue over attribution. This presents an image of two parties talking past each other rather than identifying any meaningful consensus.

Another security-related development complicating this “dialogue of the deaf” was Poland’s closure of its border with Belarus. The decision to halt any incoming traffic from Russia’s allied state until further notice was prompted by the large-scale Zapad 2025 military exercises, which coincided with Wang’s visit. Operations on the Polish-Belarusian border affect both sides’ economic interests, given the border’s role as a key gateway into the EU for Chinese rail freight. Yet, as Polish foreign ministry spokesperson Paweł Wroński stressed, “the logic of trade is being replaced by the logic of security.” Warsaw noted that during Wang’s visit, Beijing made no explicit requests to re-open the border. At the same time, it is noteworthy that days earlier (on September 11), Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Lin Jian described the railway corridor as “a flagship project of China-Poland and China-EU cooperation” and called on Poland to “ensure the safe and smooth operation of the express and the stability of international industrial and supply chains.”

Yet China is unlikely to treat the Polish-Belarusian choke point as a fixed obstacle. Firstly, the railway closure reportedly affects €25 billion in annual trade of goods between the EU and China – a fraction of the €732 billion in goods exchanged between the two sides in 2024, primarily by sea. Secondly, shippers can re-route via the Middle Corridor that bypasses Russia and Belarus. Although more costly and capacity-constrained, the corridor has been expanding and is explicitly designed as a resilience hedge for Eurasian trade. In this context, Poland has limited leverage over China to (re)shape its ties with Russia. Notably, even Polish stakeholders are increasingly investing in the Middle Corridor, as illustrated by the Polish National Development Bank’s investment in the Port of Burgas, an emerging node on this alternative logistical route.

Chickens Can’t Fly: Poland’s Economic Ambitions vis-à-vis China

This divergence in strategic outlook is not limited to hard security. It also bleeds into economics, where hopes for pragmatic cooperation often run into the reoccurring pattern of reactive overtures and unfulfilled potential. Agricultural trade offers a telling example.

During Wang’s visit, one issue proved to be central for both sides: restoring market access for Polish poultry in China. Imports of Polish poultry were suspended in August 2024 following an avian influenza outbreak. The newly introduced principle of regionalization was presented as a solution to this current impasse. Polish Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, Stefan Krajewski, and the Vice Minister of the General Administration of Customs of the PRC, Zhao Zenglian, signed an agreement allowing poultry exports from regions unaffected by the virus. Yet, the actual export potential for Polish poultry remains limited.

Amid Beijing’s push for food security and Poland’s marginal (and thus readily substitutable) role in China’s poultry imports, the importance attached to agricultural trade with China appears misplaced. Self-sufficiency is a core tenet of China’s food policy; accordingly, the drive towards import substitution led to a 72.6 percent decline in poultry imports between 2021 and 2024. In terms of volume, Poland, which accounts for less than 1 percent of Chinese poultry imports, cannot compete with the top three origin countries, namely Brazil (66 percent), the US (17 percent), and Thailand (9 percent). Although the Polish agriculture ministry celebrated the regionalization deal, the export conditions of 2020, when Polish poultry exports peaked, are long gone.

Overrating the agri-food trade in relations with China is hardly a new phenomenon in Poland. Successive governments – from Law and Justice (PiS), long buoyed by a rural base, to today’s “October 15 Coalition,” which includes the agrarian Polish People’s Party (PSL) – have treated Chinese market access for Polish farm goods as strategically important. But the notion of building a Polish “food empire” is a wishful thinking overlooking a more complex reality: Beijing’s record of routinely weaponizing agri-food trade as part of its economic statecraft. Lithuanian grain exporters have learned this after Vilnius’ pivot to Taipei. Clinging to an export mirage in a market that can be switched off for political reasons is not a strategy, but rather a self-inflicted vulnerability.

If Poland’s agri-food ambitions reveal the limits of economic engagement with China, its growing ties with Taiwan illustrate an alternative path – one that increasingly shapes Beijing’s calculus in CEE. The Taiwan factor, long downplayed in Poland’s foreign policy, is no longer a footnote – and Wang’s visit suggests that Beijing is paying attention.

Malicious Rhetorical Games: The Taiwan Factor

Wang’s visit can also be seen in light of Poland’s expanding ties with Taiwan. While Poland has been deemed a “vanguard” of closer CEE-Taiwan ties, it has assumed a more cautious stance than the Czech Republic and Lithuania. Nevertheless, in November 2024, a long-standing taboo was broken: Taiwanese foreign minister Lin Chia-lung made a fully publicized visit, which included participating in the Taiwan-Poland Economic Cooperation Conference, signing an MoU between chambers of commerce, and donating generators and made-in-Taiwan laptops for Ukrainian cities. While Lin’s predecessor Joseph Wu set foot in Poland twice, his visits were kept low profile and largely off the record, with the 2021 visit entirely non-public, and the 2023 visit acknowledged only on the website of the Warsaw School of Economics. Consequently, Wang’s travel to Poland may also be understood as an effort to counter Taiwan’s growing footprint in the country.

It is also speculated that Poland may host a high-profile government visit from Taiwan during the upcoming Warsaw Security Forum, a prominent platform for security and defense policy dialogue. At last year’s event, the organizers welcomed Deputy Secretary General of Taiwan’s National Security Council Lin Fei-Fan as one of the speakers, and expressed their intent to elevate exchanges with Taiwanese authorities further.

Overall, Poland’s economic aspirations have allowed for the intensification of informal, project-level exchanges with Taiwan. The country’s first national semiconductor strategy explicitly identified Taiwan as a pivotal partner in Poland’s pursuit of technological autonomy and integration into global supply chains. The Semicon Taiwan trade show has also served as the leading platform for showcasing Poland’s growing interest in semiconductor engagement. Since 2023, it has hosted the Polish national pavilion, which has been inaugurated at the level of deputy minister. Cooperation is also flourishing in other areas, including hydrogen technologies and UAVs. Against this background, Beijing’s references to possible cooperation with Warsaw in strategic sectors, including electromobility, appear more reactive than proactive, designed to implicitly counter Taipei’s offers.

Despite the symbolism of the poultry agreement, tangible achievements from Wang Yi’s visit remain limited. The trip revealed two sides largely talking past each other. China’s outreach was reactive, shaped more by shifting circumstances than proactive engagement, while Poland’s hopes of leveraging dialogue to drive a wedge between Beijing and Moscow appear misplaced. In reality, China’s positions are transactional, offering little beyond rhetoric, while Poland has few tools to influence Beijing’s strategic calculus. As security eclipses trade in the bilateral agenda, the outcome is an uneasy relationship defined more by parallel monologues than meaningful progress – a dynamic unlikely to change anytime soon.

Written by

Marcin Jerzewski

yehaoqinMarcin Jerzewski is the Head of Taiwan Office of the European Values Center for Security Policy. He is also a Marcin Król Fellow at Visegrad Insight. Marcin earned his Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Chinese Studies at the University of Richmond and was an MOE Taiwan Scholar in the International Master’s Program in International Studies, National Chengchi University.