Lithuania’s WTO Case and Why It Won’t Change Anything

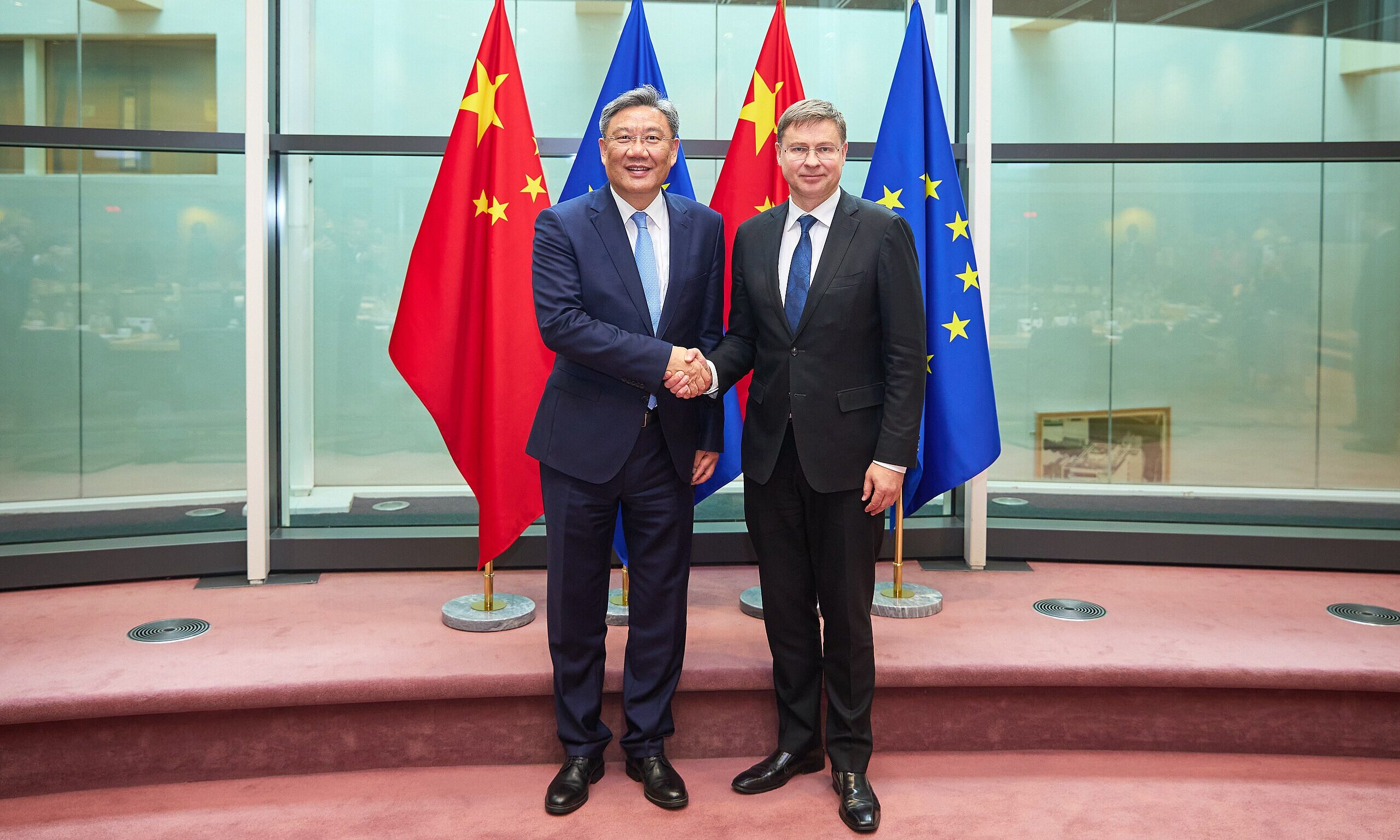

In recent years, China has readily employed various coercive, protectionist and anti-free trade practices to its benefit. With EU Commissioner for Trade Valdis Dombrovskis’ visit to China in late September for trade talks, the attention once again turns back to the half-forgotten dispute over the Chinese embargo on Lithuania in the World Trade Organization (WTO). How is it going so far?

This article is part of a series of articles authored by young, aspiring China scholars under the Future CHOICE initiative.

The short answer would be: “Slow.” The slightly longer answer might be: “As well, as one would expect from the WTO.” Regardless of the answer, let’s first take a look at why the Chinese embargo even happened.

Problems in Lithuania-China bilateral relations began to emerge with the election of a center-right government in the autumn of 2020 that promised a value-based foreign policy with respect for human rights and a more assertive stance towards Beijing. A seemingly significant ‘escalation’ came in May 2021 when the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced its withdrawal from the 17+1 platform (now “the 14+1”), and the new Lithuanian Foreign Minister cited the divisiveness of the platform as the main reason for Lithuania’s departure. In the same interview, however, he advocated for a 27+1 format: “The EU is strongest when all 27 member states act together along with EU institutions.”

It was not until late November 2021, however, when Taiwan opened its representative office, that fire began raining down on the Lithuanian government – from the opposition, former leaders, the country’s President, and China.

The representative office was not named after the country’s capital – Taipei – as is the diplomatic custom, but rather the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius. China consequently downgraded the bilateral diplomatic relations and soon after, Lithuanian business experienced first problems with the Chinese customs systems. It appeared as if Lithuania as a whole disappeared from China’s customs IT systems altogether. At the same time, Lithuanian goods were not being processed in ports and were blocked from obtaining customs clearance. Furthermore, China also blocked products from other countries that contained any Lithuanian components whatsoever.

As such, this affected more countries than just Lithuania, and soon, companies from Germany, Sweden and France reported issues with Chinese customs authorities. Nonetheless, even though reports of a widened embargo began to spread at that point (early December 2021), the EU was unable to react in any way. The tools it needed to have were in the stage of development at the time – especially the Anti-Coercion Instrument devised under the guidance of the Commissioner for Trade Dombrovskis.

The WTO Case

In January 2022, the European Commission requested consultations in the framework of the WTO over the issue, which, at that point, became an effective embargo on almost all Lithuanian exports to China. The EU, in its Request for Consultations to the WTO Secretariat, called Chinese restrictions “novel, numerous, recurrent, persisting and strongly correlated in temporal and substantive terms” and summarized them into three categories: import bans or restrictions, export bans or restrictions and restrictions or prohibition on the supply of services.

The legal basis of the request is based on several articles from the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), specifically articles that introduced the concept of most favored country treatment (the notion that every country has to be treated equally, i. e., lowering tariffs for one country means that tariffs have to be decreased for every other WTO member) and articles that describe the implementation of GATT (and, consequently, other regulations) which is supposed to be: “uniform, impartial and reasonable.” This is, of course, in stark contrast with the Chinese embargo as described by the Commission.

While there are often a few countries requesting to join the WTO consultations, usually one to three in the case of disputes initiated by the EU, the number of countries that requested to join the EU-China consultations over the embargo on Lithuania has been much higher.

In the usual fashion, Japan joined, as well as Canada and Taiwan; however, unexpectedly, even countries like the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia requested to join the consultations.

Although all had different reasons to join, some stuck out more than others. In its official statement, Taiwan mentioned that it would be affected in the same fashion if it was deleted from Chinese IT customs systems. In turn, Australia referenced the bilateral trade exchange with China and the potential of this dispute affecting Australia’s trade through disruption in global chains. Similarly, the United Kingdom, aside from arguments on China’s relevance to its own trade balance, stressed its “systemic interest in the proper interpretation and application of the relevant provisions cited in the EU’s consultation request.”

Seemingly, most of the said countries requested to join the consultations mainly out of the fear of the same ‘problems’ happening to them, as well as the potential impact of China’s moves on global supply chains. Interestingly, in its request to join, the US mentioned both sides of the case as a relevant trading partner, pointing out that the US and the EU share “the largest economic relationship in the world.”

Drawing Parallels

While the case is not anywhere near resolution, it is fascinating to see how much interest from EU trading partners across the world it has attracted.

In the EU’s dispute settlement history, there has been only one other example of this much interest: the dispute over various Chinese protectionist policies imposed on various rare earths, politically connected with the Senkaku Islands Dispute between Japan and China. While the European Union was not the principal actor in the 2012 case, it launched consultations with China, similar to Japan and the United States. Later, these three separate cases came to be reviewed by one single panel in the WTO Dispute Settlement Body.

As with Lithuania, Japan’s dispute was also about Chinese coercive economic actions. In this case, export duties were suddenly imposed on several rare earths, tungsten and molybdenum following the detention of a fishing boat captain near the disputed Senkaku Islands (also called Diaoyu Islands) in the East China Sea.

Although the dispute between China and Japan, the EU, and the US ended with China dropping its export duties on rare earths, tungsten and molybdenum, it is debatable at best whether it was due to the WTO Dispute Settlement Body findings or simply since the measures at hand were not needed anymore as sending a signal was perhaps more important for China at the time.

Similarly, though portrayed as an ‘escalation’ by the media in the EU-China trade kerfuffle, the Commission’s request for consultation was more of a consolation gesture to Lithuania. As many politicians, diplomats and experts pointed out in recent years, the WTO does not work as it should. The dispute settlement process is, at best, slow and often ends years after it began, which is problematic when the situation calls for a quick reaction to economic bullying. In the end, the WTO might call upon China to end its embargo on Lithuania, even backed by a Dispute Settlement Body decision; nonetheless, Sino-Lithuanian trade exchange will never be the same.

While the WTO is notoriously known for not being functional, in particular when it comes to the big players like the EU, the US or China, it now seems that the EU is looking into defending its market and members through rather protectionist techniques – aforementioned Anti-Coercion Tool or the Commission’s probe into Chinese subsidies to the sector of electromobility. The question now is whether these mechanisms will serve as a deterrent in the world of free trade or an escalatory measure forcing more countries to build barriers.

And the Winner Is?

Is the situation for a rule-based international system really so bleak? Well, no – at least not for Lithuania.

As the Commission is now calling for de-risking from China, Lithuania might be a good example of how a prompted derisking, or even a decoupling might look like in practice. Economic reports suggest Lithuanian businesses have already offset the loss (as of 2022) of the Chinese market by increasing its exports to Indo-Pacific markets. Apart from that, Lithuania has the consolation prize of having an entire WTO dispute dedicated to itself.

Written by

Matěj Hulička

mhulickaMatěj Hulička is an intern at China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe (CHOICE) and MapInfluenCE projects.