Since the late 1980s, China has actively signed Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) with every country in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) apart from Montenegro. These treaties remain effective today and oblige CEE countries to afford protection for Chinese investment, and vice versa. If countries in CEE breach such treaty obligations by harming Chinese investment, they face the risk of investor-state arbitration with Chinese investors. Indeed, in May 2019, the first publicized arbitration between a CEE country and Chinese investors was initiated against the Greek government under Greece-China BIT.

Despite this legal instrument, most discussions about China’s investment in CEE have shed light only on its economic and geopolitical dimensions. Although most CEE-China BITs will be replaced by the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment in the future, they still hold implications for CEE policymakers to consider, especially as Chinese investments grow in the region.

China’s BITs in a Nutshell

China has the second largest BIT network (125) in the globe, after Germany (129). As with other typical BITs, China’s BITs require that state parties guarantee foreign investment protection based on substantive standards. Such standards include non-discrimination principles (most-favored-nation treatment and national treatment) as well as fair and equitable treatment. Moreover, an expropriation provision is a key BIT element that mitigates an important risk faced by investors. Expropriation clauses do not take away States’ right to expropriate (or nationalize) property, but make the exercise of this right subject to certain conditions.

China’s BITs also have a provision on Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), which has a significant role in enforcing substantive rules. Namely, it typically allows damaged foreign investors to sue their host States in international arbitration if host states allegedly breached their treaty obligations. In case arbitral tribunals rule in favor of a damaged investor, the claimant can rely on the award and seek financial remedy from the host state.

All CEE-China BITs contain these substantive and ISDS provisions. This means that 16 countries in CEE, except Montenegro, are legally required to ensure protection of Chinese investment under respective BITs. More importantly, if they fail to observe the treaty obligations, they could face legal challenges by Chinese investors in international arbitration.

Why are CEE-China BITs Forgotten?

According to the UNCTAD, as of 2019, countries in CEE, have already appeared in over 200 arbitration cases as respondent States. Among 108 decided cases, tribunals found that CEE countries breached BIT obligations in 33 cases and were ordered to pay restitution. The amount of the restitutions ranges from $400 thousand (Swisslion v. North Macedonia) to $ 867.8 million (ČSOB. v. Slovakia).

Given that CEE countries have rich experience in this field, one may wonder why sufficient attention has not been paid to CEE-China BITs. A possible explanation from a legal perspective is that a majority of CEE-China BITs arguably lack effective enforcement mechanisms. That is, ISDS provisions of those BITs limit the material scope of judicial review by arbitral judges and leave most substantive standards practically ineffective.

Specifically, such an ISDS clause provides that investors can initiate arbitration over disputes regarding the amount of compensation for expropriation. A simple reading of this requirement would mean that disputes over substantive standards other than expropriation are excluded from international arbitration, and that disputes regarding expropriation must be related to the amount of compensation, not to the existence of expropriation. For investors to invoke this limited ISDS clause, it would be a prerequisite that host states voluntarily proclaim the existence of expropriation in the first place. This clause would create a high legal threshold for investors because host states rarely admit their expropriatory acts on a voluntary basis. Indeed, the existence of expropriation itself is one of the most frequent disputes brought under international arbitration, accounting for almost half of all total cases (502 out of 1,023). Exclusion of such disputes, to say nothing of other substantive standards, makes BITs virtually toothless.

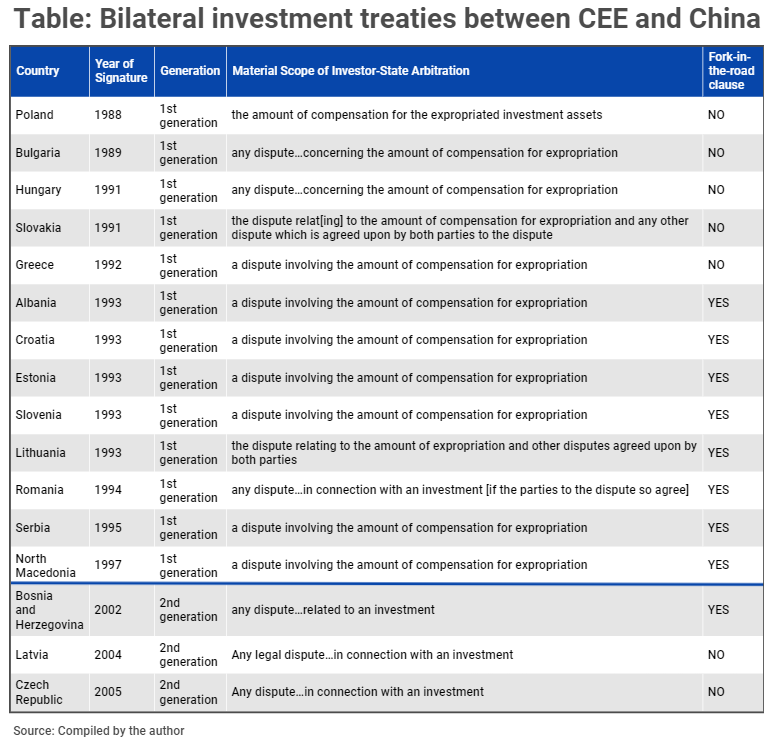

This restrictive ISDS clause is contained in 12 out of 16 CEE-China BITs. Those 12 state parties include Poland (1988), Bulgaria (1988), Hungary (1991), Slovakia (1991), Greece (1992), Albania (1993), Croatia (1993), Estonia (1993), Slovenia (1993), Lithuania (1993), Serbia (1995) and North Macedonia (1997). Romania-China BIT (1994) is exceptional in that the arbitration clause could cover any dispute in connection with an investment if the parties to the dispute (i.e. both a host state and an investor) so agree.

In contrast, three CEE-China BITs -Bosnia and Herzegovina (2002), Latvia (2004) and the Czech Republic (2005) – are very different from others due to the provision of a robust ISDS arrangement. That is, regarding disputes covered by international arbitration, it is broadly stipulated that arbitrators can deal with “any dispute related to an investment” or “any legal dispute in connection with an investment.”

The change of China’s position on ISDS clause coincides with the shift of its status from a capital importing country to a capital exporting country. China signed the first twelve restrictive CEE-China BITs (first-generation BITs) when it was merely a capital importing country. Thus, China did not need an effective ISDS mechanism to protect its overseas investment. Moreover, as one tribunal pointed out, China’s restrictive ISDS clause reflects “a certain degree of mistrust or ideological disagreement on the part of communist regimes regarding private capital investment” as well as “a concern about the decisions of international tribunals on matters such regimes are not familiar with and over which they have no control.”

On the contrary, the latter three CEE-China BITs (second-generation BITs) were signed against the backdrop of China promoting its “going-out strategy” starting from 2002. For example, China, as a part of the campaign, began overseas investments in the area of natural resources. This necessitated China to insert an effective ISDS clause into its BITs so it could hedge the associated investment risks in foreign territories by means of international arbitration.

Transforming Toothless Agreements into Effective Treaty Tools?

A simple observation of CEE-China BITs indicates that only China’s second-generation BITs effectively require protection of Chinese investments. Nevertheless, recent arbitral decisions under other China’s first-generation BITs determined that investors could broadly interpret the restrictive ISDS clause to cover disputes over the existence of expropriation as well. Although these arbitral decisions do not have any legal precedence, they strongly suggest that Chinese investors could do the same under the CEE-China first-generation BITs.

At a time of writing, there are four cases where Chinese investors brought expropriation claims under China’s first-generation BITs. Among four cases, three tribunals (Tza Yap Shum V. Republic of Peru, Sanum Investment V. Laos (I), and Beijing Urban Construction V. Yemen) upheld a broad interpretation of the ISDS clause.

To support this broad interpretation, the tribunals first pointed out that if host states do not admit the existence of expropriation, domestic courts in host states would automatically become the only litigation forum for damaged investors to bring expropriation claims. According to the tribunals, this situation contradicts another BIT provision (i.e. fork-in-the-road clause) under China’s BITs that gives investors a choice as to a favorable litigation forum between domestic courts and international arbitration. Thus, tribunals held that as long as a BIT at issue provides investors a choice of the forum, investors should be entitled to bring expropriation claims before international arbitration at their choice. As shown in the table below, such a clause is contained in seven CEE-China first-generation BITs.

It’s Time to Recall Old Promises

While careful analysis of individual BIT and facts is of paramount importance, it has been suggested that CEE-China BITs, both first and second-generation, are effective enough to pave a way for Chinese investors to have a recourse to arbitration. The obvious takeaway from this analysis is that it is essential for CEE countries to frame policy towards Chinese investment in accordance with the BIT obligations. Ignoring such obligations could lead to unwanted arbitrations with Chinese investors.

First, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Latvia and the Czech Republic must take into account all of the substantive standards of protection under respective BITs, as any breach of those standards could be within the scope of arbitration under China’s second-generation BITs.

Moreover, as illustrated above, countries with first-generation BITs should consider whether their legislative acts or administrative decrees affecting Chinese investments could constitute an unlawful expropriation under the terms of CEE-China BITs. In this regard, established jurisprudence shows that host states could indirectly expropriate foreign investments by depriving its economic value. Examples of indirect expropriation include forced divestment of shares of a company, interference in the right of management, and deprivation of licenses or contractual rights that are integral to the operation of an investment.

Indirect expropriation seems relevant in particular to the handling of China’s infrastructure projects in CEE. Due to their highly public nature, host state governments engage in many stages of infrastructure projects such as tender, negotiation, construction, operation and potentially, renegotiation. However, for the same reason, infrastructure projects could be exposed to political risks (e.g. cancelation of a project as a result of a change of administration), regulatory risks (e.g. deprivation of a concession and a change of the tariff rate) and financial risks (e.g. default of a host government). It is in this context that CEE countries face a potential danger of taking measures which could constitute unlawful indirect expropriation by frustrating Chinese infrastructure investments through administrative or regulatory acts. The danger becomes more imminent when those acts are taken sorely for political purposes.

This concern is becoming real.

In May 2019, two Chinese solar plants manufacturers brought expropriation claims under Greece-China BIT. The Chinese companies claimed that the implementation of their solar photovoltaic plant project located in northern Greece was hindered by the government, despite the fact they were entitled for a fast track licensing procedure with the qualification of a “strategic project” granted by the Greek government. Although the arbitration was withdrawn in December 2019 by the claimants, this case shows how “mistreatment” of Chinese infrastructure projects could result in costly and time-consuming arbitrations under CEE-China BITs.

Today, countries in CEE are facing increasing pressure to adjust the balance between economic interests brought by Chinese investments on one hand, and the political concerns posed by them on the other hand. In determining this balance, however, it is essential to recognize that CEE’s old promises to China could potentially constrain their future policy.

Written by

Hiroki Yamada

Hiroki Yamada holds a LLM degree in International Economic Law from the University of Edinburgh in the UK. He was a former Research Intern at the Institute of International Relations in Prague, and also an Investment Promotion Ffficer at the Danang Investment Promotion Agency in Vietnam.