Are China and Iran Forging a New Geopolitical Axis in Eurasia?

Pressure on Iran and its nuclear program has not relented with a new administration in Washington, which Tehran has taken as a signal it must maximize its efforts to balance Washington’s clout by building closer ties with China. At the same time, this offers significant benefits to China. By anchoring itself in the region via Iran, China aims to integrate what Beijing refers to as Western Eurasia deeper into its Belt and Road Initiative.

Potentially Groundbreaking Deal

Beijing and Tehran are preparing a 25-year economic and security deal according to which China would invest up to $400 billion in Iran. The proposed deal would give China access to modernization projects and bids in Iranian railroads, ports, and 5G networks. The agreement could also give Beijing access to Jask, a major Iranian port outside the Strait of Hormuz and discounted supplies of Iranian oil and gas for the next 25 years. Additionally, free trade zones are to be created in Maku in the northwest, Abadan near Iraq, and Quesham—an island strategically located in between the Persian Gulf and the strait of Hormuz. If implemented, the deal would allow Iran to cement its position within China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The agreement would mean significant strengthening of security cooperation between Beijing and Tehran. It would bring qualitative and quantitative increase of joint military training and exercises (the latter trend is already widely observed), research and weapons development, and sharing of intelligence.

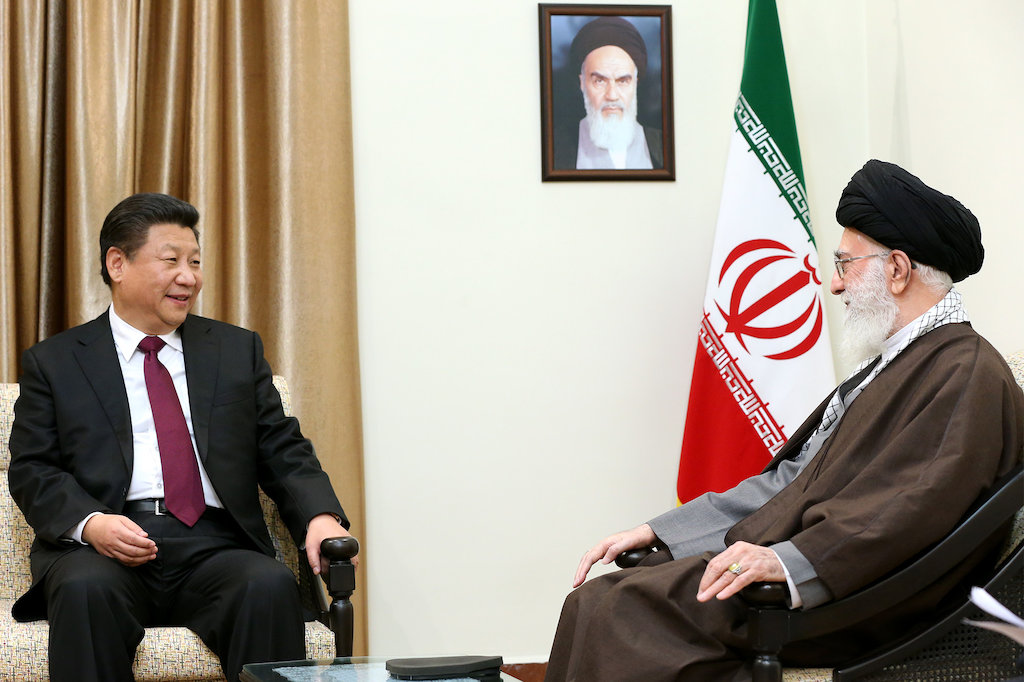

The green light for these negotiations came shortly after the Iran nuclear deal in 2016, when Chinese President Xi Jinping made a historic visit to Tehran to meet Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Though US pressure serves as an undeniable sticking point for China and Iran, there is much more to the story. Iran’s turn to China has been in the works for years and the proposed deal is the Iranian political elite’s natural reaction to the geopolitical opportunities presented by the rise of China.

As geopolitical gravity is shifting from the Atlantic to the Indo-Pacific, the increasingly close China-Iran ties accentuate geopolitical changes in Eurasia. Geopolitical opportunism is at play as Tehran seeks Beijing’s support in its travails with Washington while China tries to avoid encirclement by US allies.

There is also purely economic opportunism – Iran is, quite naturally, interested in engaging with the emerging Eurasian powerhouse. Iran set its eyes on China already more than a decade ago when under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad who initiated the ‘Look to the East’ program, China became Iran’s major trading partner.

Nevertheless, the growing intensity of the pivot to the East is also simply driven by Iran’s lack of options. Though Iran is aligned with Russia in many sectors, their mutual distrust in a number of geopolitical theaters (namely in the South Caucasus and occasionally in Syria) prevents Tehran from relying on Russia’s Eurasian alternative (Eurasian Economic Union).

Nor is the collective West an option. Even if the Europeans may not be entirely on board with US pressure on Iran, overall they are unwilling to break entirely with Washington’s policy. Further afield, another big player, India, does not provide a significant regional integration project to rely on. Thus China is the only viable way for Iran to alleviate its difficult economic situation, diversify its foreign policy and seek vital international support from a major power.

Geopolitical Chessboard

If the deal is signed and implemented, it would accelerate two major geo-economic trends— China’s growing investment in the Middle East and the consolidation and spread of illiberal authoritarian anti-American bloc of countries.

But the distrust both China and Iran share toward the collective West (plus Russia) is also driven by the states’ mixture of geography and historic experiences. With major geographic barriers (deserts, mountains etc.) surrounding the densely populated Iranian and Chinese heartlands, Chinese and Iranian psyche if immersed in a fear of foreign encirclement.

Both states also find common ground with regard to connectivity across the Eurasian landmass and see themselves as central to any large-scale infrastructure projects or trade routes spanning the continent. This centrality on the ancient, and now modern Silk Road, is a cornerstone of the Chinese and Iranian geopolitical self-perceptions. To this end, the proposed agreement suggests Iran’s deeper integration within the BRI.

A much bigger geopolitical trend that pulls China and Iran closer is the idea of an emerging multipolar world. Both states seek limits on US power and try to pursue independent foreign policies. This geopolitical glue proves to be a significant long-term motivator for both states, plus other illiberal countries to build an understanding among each other.

For Iran, closer ties with China are also about its historical strategy of hedging against larger geopolitical rivals. Today it is the US, earlier it was Russia, and before that the Ottomans and so on.

China also boosts Iran’s efforts to portray itself as a civilizational crossroads. Iran has pursued a port and railway development strategy which now forms a part of a bigger move to position itself as an interconnector of Indian, Chinese and Russian economic projects.

China does not just seek to create corridors linking it with Iran, but also enables Iran to open up Central Asia, In this undertaking, the expansion of railways and roads is critical. In August 2020, Iran unveiled two corridors into Central Asia: the Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan-Afghanistan-Iran (KTAI) route and the Iran-Afghanistan-Uzbekistan routes.

No Shortage of Obstacles

The proposed Iran-China deal is huge, but the widely held assumption that the deal will be completely fulfilled is debatable. A larger picture invites much caution. Chinese investment in Iran has averaged $1.8 billion per year since 2005. In 2005-2018, China invested less in Iran than in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. This picture is unlikely to change overnight even with the proposed deal being inked.

US sanctions will also remain as a key deterrent to FDI into Iran. The Chinese have been hesitant to undermine their international position over anti-Iranian sanctions, just as they had been cautious in their relations with Russia, namely unwilling to invest into Russia for the fear of international sanctions.

Other aspects of China-Iran economic ties also show a less positive picture. Chinese companies have a record of trying to exploit Iran’s lack of economic alternatives by demanding tougher trade terms, setting high prices, and bringing little economic benefits to the local workforce and national budget.

There is also a negative background to China-Iran cooperation. In 2012, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) stopped operations at the South Pars natural gas field when Iran moved to abrogate the company’s contract. CNPC was later substituted with Petropars. In 2014, another of CNPC’s contracts—the Azadegan oil field—was canceled. Thus, promises of large-scale investment laid out in the deal may be difficult to implement for China, while those projects which would eventually take off the ground will likely be negotiated under unfavorable terms for Iran.

In Iran there is also a general distrust toward great powers. If all the points in the proposed deal are carried out, Beijing is risking causing ire among the Iranian population, always sensitive to foreign powers and a specter of ceding sovereignty.

Tempering Expectations

Regional and wider Eurasian geopolitics are pulling China and Iran closer as both countries appear to need each other. Still, the engagement is fraught with potential problems for Iran, even if benefits could be huge. Negative historical experience with unsuccessful investment lingers and the likelihood remains that China would seek to exploit Tehran’s relatively weak bargaining position. Nevertheless, in partnering with China, Iran is still likely to find a significant economic lifeline too, which it would use to improve its weak economic position. Tehran uses the benefits of geographic location to serve as a jumping point for China’s BRI to expand to West Asia— a ‘civilizational crossroads’ idea cherished by the Iranian political elites.

Though some changes to the leaked text of the deal are likely to happen before the agreement is signed, both parties are set to gain in some form. Beyond economics, both Beijing and Tehran are motivated by wider geopolitical processes—limiting the Western influence and potentially even gradually establishing a new order from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea. This will serve as a glue for two Eurasian states to increase cooperation on non-economic issues such as in the military and diplomatic spheres.

Written by

Emil Avdaliani

emilavdalianiEmil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of silk roads.