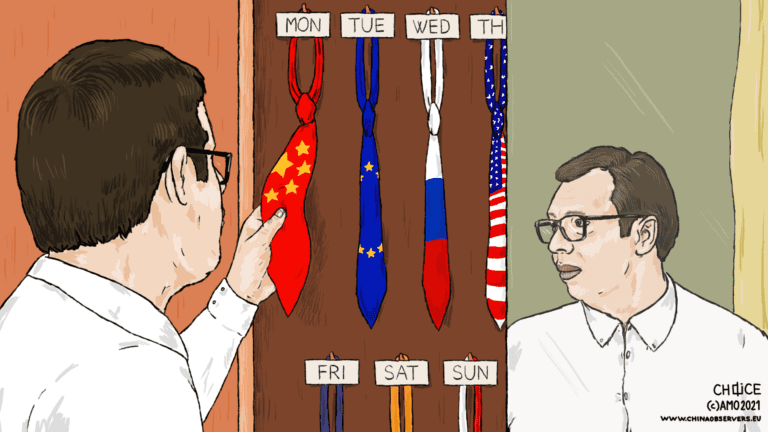

While China has been using economic pressure to make countries around the world refrain from stepping over some of its “red lines”, the Western Balkan region serves as an example of a rather opposite trend. Serbia’s experience showcases that those countries that are willing to align closely with China’s (geo-)political interests are likely to be rewarded with economic benefits.

On May 7, 2024, marking the 25th anniversary of the NATO bombing in Serbia, when the Chinese Embassy was hit, Chinese President Xi Jinping arrived in Belgrade for a two-day visit. Despite the fact that the unfortunate event brought the two countries closer into an “iron-clad friendship”, the focus of the visit was the future rather than the past. Around 30 bilateral agreements were signed paving the way towards a “shared future”, with Serbia being the first country in Europe to endorse the new Chinese concepts for redefining the existing world order – the Global Development, Security and Civilization Initiatives.

As a reward for the outstanding bilateral ties and for having China’s back in multilateral fora, in the past decade, Serbia has seen a surge in Chinese investments, welcomed unprecedented levels of Chinese tourists and received loans for infrastructure funding, increasingly intertwining its economy with China and occasionally making the other countries in the Western Balkans envious.

However, cooperation with China and potential economic benefits do not come without “strings attached.” Oftentimes, the conditions that Serbia puts in place to attract and please its Chinese partners collide with the obligations that the Western Balkan countries need to fulfill as part of their aspirations to join the EU. Moreover, the cooperation involves a high degree of economic dependence on China which, as practice shows, at some point becomes a liability outweighing the benefits of economic engagement.

Learning from the Experiences of Others

A number of examples around the world showcase China’s willingness to use economic tools to pressure other countries to act (more) in line with its own positions and expectations. In 2010, when Norway awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, China introduced strict controls on every shipment of Norwegian salmon, leading to a serious drop in the import quantity. As Sweden awarded a human rights prize to Gui Minhai, a Chinese jailed publisher and dissident in 2019, China introduced a ban on the export of graphite to Sweden, creating serious problems for battery producers. After H&M stated that it will no longer use Xinjiang cotton in its products, it was wiped off the Chinese retail websites and ’spontaneously’” boycotted by Chinese consumers. In 2020, as Australia labeled Huawei a security concern and called for an independent investigation into the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic, China banned the imports of Australian coal. The list of such cases goes on to include Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan and closest to the Western Balkans – Lithuania, after the country allowed the opening of what was called “Taiwan,” instead of “Taipei,” Representative Office.

The embargo on Lithuanian goods threatened the entire European single market as China banned the imports of all products containing Lithuanian components, putting at risk for instance the exports of German cars, among other goods. As a response to that incident, as well as the new reality that China is increasingly willing to use its economic clout to push forward its (geo-) political objectives, the EU introduced de-risking as a new concept underpinning its economic relations with China. Those cases should also serve as a learning experience for the Western Balkan countries in their delicate balancing act: how to continue the economic cooperation with China and at the same time align with the positions of the EU (and NATO for some of them).

Economic Benefits Significantly below Expectations – Everywhere but in Serbia

All the countries in the Western Balkans participating in the China-CEE cooperation platform have seen an increase in the trade volume with China, doubling or even tripling (in the case of Serbia) the import of Chinese goods. China ranks among the top import partners and the composition of Chinese imports is roughly the same throughout the region – electronics, machinery, iron and other metal products, chemicals, consumer goods such as textiles and footwear. This is largely due to the low purchasing power of citizens, as well as the low competitiveness of local companies, which see a lifeline in importing relatively cheap production inputs and equipment.

When it comes to exports though, only Serbia has managed to achieve a significant (10-fold) increase, while exports from the other countries, albeit also increasing, display a very uneven trend throughout the years. In 2022, Serbia’s exports to China amounted to over 90 percent of extractive products, displaying a rather worrisome trend which extends across the region: China has been directing the trade relationship towards satiating its thirst for raw materials, while at the same time tacitly restricting market access for products with higher value added. For instance, Montenegrin exports to China, which soared in 2022, predominantly (almost 90 percent) consist of aluminum ores. In Albania, over 80 percent of exports consist of chromium and copper, mostly mined by Chinese companies. In North Macedonia, the year 2022 is the first time when ferroalloys did not make the bulk of the exports. Instead, minerals dominated, such as marble, travertine and alabaster accounting for 44.4 percent and, for the first time, there was one third of the exports consisting of electrical and motor parts and components. Bosnia and Herzegovina is the only country with more diversified exports to China, where in addition to extractives, which accounted for approximately one third in 2022, exports include end products with higher value added, such as clothing garments.

China’s ability to control market access, or provide it to those countries that are ready to engage in closer bilateral cooperation, can also be seen through the number of bilateral agreements signed to facilitate exports to China, mostly of agricultural products, that remain empty words on paper. The persisting non-tariff barriers, in addition to most Western Balkan countries’ limited production output, competitiveness and capacity to unilaterally change the situation lead to the low level of exports. On the other hand, Serbia is continuing to advance its access to the Chinese market through the FTA it signed in 2023, although it will arguably also open the door for more Chinese imports, as well as exports of extractives, namely copper.

When it comes to investments, China stands at the 4th place for total investment stock to the Western Balkans, with €4.369 billion at the end of 2022. However, €4 billion, or the quasi-totality of the investments, is located in Serbia, while in the other countries, China is not even ranked among the top 10 investors. In that sense, although Serbia is arguably the biggest and most attractive economy in the region, China has adopted a strategic approach and opted not only for commercial investments, but also for acquisitions that could bring other advantages.

For instance, in 2016 the state-owned Hebei Steel (HBIS), China’s biggest steel company acquired Smederevo steel plant, a company that the Serbian government had been trying to privatize and make profitable for years. The deal with HBIS as the only bidder, which amounted to €46 million, followed a previously signed Memorandum for Understanding and active lobbying by the Serbian government to find an investor for what had become a priority project for President Vucic. The offer was also attractive for the Chinese as it allowed them to gain ownership of their first plant outside of China, amidst the rising tensions between Beijing and Brussels on the exports of cheap Chinese steel to Europe. Ever since, the Chinese-owned steel plant has become one of the top three Serbian exporters, selling a significant part of its steel on the EU market. On the other hand, Zijin Mining, the next big Chinese investment in Serbia in copper and gold mining, is exporting predominantly to China, securing a part of China’s pressing need for copper, a critical raw material which has also become a priority for the EU.

Building the Roads to Dependence?

With the exception of Albania, all the Western Balkan countries have engaged in building large infrastructure projects with Chinese capital, with Serbia again being “the leader” with around 90 percent of the total loans amount provided by China in the region. Local policy-makers have preferred the option – in most cases of loans from the Export-Import (EXIM) Bank to the use of EU funds or loans as it enabled project implementation to start swiftly, rushing through the phase of project preparation. However, the lack of serious approach and due diligence in the preparatory phase often entailed serious issues and overruns in the implementation, as seen for instance in the highway construction projects in Montenegro and North Macedonia.

As the beneficiary governments strived to find a way out, they realized that it was very difficult – bordering impossible to get out of the loan contracts, concluded on the basis of a Chinese EXIM bank model agreement which provides China with the prerogative to arbitrarily suspend or terminate the agreements and sets arbitration in Beijing, under Chinese legislation. Thus, in addition to the high burden on public finances, especially for countries like Montenegro, Chinese loans bind recipient countries to China in a highly asymmetric relationship which could be leveraged by China to its advantage.

In the case of the Western Balkans, China has created, but not weaponized the asymmetric economic dependence. Instead, the experience thus far shows a different Chinese approach – “positive” conditionality for those countries that choose to deepen and prioritize cooperation with China. Namely, Serbia continues to strengthen its position of a regional frontrunner, as the country which welcomes and enables close cooperation with China, including in sensitive areas such as security and defense. That commitment is appreciated and rewarded by China with investments, market access and capital for infrastructure projects, which in turn additionally deepens Serbia’s economic dependence on China.

Written by

Ana Krstinovska

Dr. Ana Krstinovska is a Research Fellow at CHOICE, President of the North Macedonia-based think tank and consultancy ESTIMA and Research Fellow at the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy ELIAMEP.