India has traditionally championed the principles of strategic autonomy and non-alignment as core guiding tenets of its foreign policy. However, in recent years there have been marked shifts, most notably in its security and economic ties with the EU, that suggest a recalibration of India’s outlook. This development can be attributed to the growing influence of the ‘China factor’ in India’s calculations – a potential game-changer in EU-India relations.

Since 1947, New Delhi has maintained a stance of ambivalence and hesitancy to commit to any particular security arrangement. The only notable exception was its relationship with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, which was born out of necessity and influenced by the US’ moves vis-à-vis Pakistan and China.

Now, the context has changed. The resurgence of great power competition, global shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic – and the revelations it has brought to light in terms of economic (inter)dependence – and most recently, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, have highlighted the challenges India faces from China under Xi Jinping’s leadership.

Sources of China-India Tensions

The ‘China factor’ in Indian foreign policy can be broken down into three main variables.

First, India’s long-standing border disputes with China remain a critical concern. Recent clashes, including a fatal episode in June 2020 that resulted in the death of 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese casualties, signify a culmination of the recurrent disputes along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). These clashes are fueled by the lack of a common demarcation of the border and increased infrastructure development by both sides.

Tensions have been further exacerbated by the shifting dynamics of their bilateral relationship, particularly in terms of economic power and defense expenditures, and by Xi Jinping’s imprint on Chinese foreign policy. Under his leadership, China has taken a far more muscular and proactive stance on sensitive issues concerning the country’s sovereignty claims, such as in Hong Kong, Taiwan, the South China Sea, and, what is crucial for New Delhi, also the Sino-Indian border.

A multitude of other pain points have prevented the soothing of India-China relations and have become more salient over time considering the overall context of the bilateral relationship: India’s support of the Dalai Lama, its rejection of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the noteworthy commercial trade surplus in favor of China which reached $100 billion in 2022, India’s participation in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, and the close Sino-Pakistan relations, inter alia.

As long as infrastructure investment and, consequently, the militarization of the border areas increases on both sides, India and China are set to continue to clash over the border lacking common demarcation. Discussions at the ministerial and commander level, instituted to cool down the tensions, simply reiterate the same story without any concrete outcomes or a clear evaluation of the situation on the ground. This empty rhetoric may temporarily minimize the tensions between the two countries, but it fails to make any meaningful progress. India is no longer content with ‘business as usual’ with China, and this only serves to illustrate the fact that if no progress is made, the Sino-Indian border disputes will only further entrench.

In June 2020, China and India closed a stage of managing their differences along the LAC without any fatalities. Since then, they have entered a new phase, as pointed out by Rana Mitter, in which one must deal with “a state which no longer apologizes for being authoritarian” and which is currently the second largest economy in the world. Indeed, since the momentous agreement between Rajiv Gandhi and Deng Xiaoping in 1988 to put border disputes aside and pursue cooperation in other areas such as trade and culture, the relationship between the two countries has undergone a significant transformation.

Second, India is increasingly concerned about the Sino-Russian alignment. Due to a set of different geopolitical developments, Sino-Russian relations have been steadily improving even before the invasion of Ukraine, with the two countries bound together by their opposition to the US.

India’s abstention in nearly all UN votes against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reveals that its partnership with Russia has a staying power. Although India toughened the language it used in its statements over time, it still chose to abstain, rather than explicitly condemn the invasion. A key reason is India’s dependence in military technology and equipment on Russia, a longstanding situation that dates back to the Cold War.

Yet, the other factor is its hesitance to push Russia closer to China, its greatest threat. Russia joining the existing hostile axis of Pakistan and China would be catastrophic for India. In the past, New Delhi was able to count on Moscow’s support to balance its regional security concerns from China and Pakistan. However, as relations between Moscow and Beijing grow closer, Russia’s involvement in India’s security policies is likely to decrease over time, though not in the near-term.

These elements signal that India’s relationship with Russia is deep-rooted in history yet maintained out of necessity for its own interests. India is aware of the Sino-Russian alignment, yet remains pragmatic, opting for convenience. The signing of agreements with Russia to acquire more crude oil at a comparatively low price is just an example of this approach.

Third, China’s presence in India’s immediate neighborhood has been a cause of concern for several years, but since Xi Jinping came to power and rapidly adopted a more assertive foreign policy – from which South Asia is not exempt, these concerns have become more salient. In fact, China has been actively seeking to influence the region through leveraging political ties and investing heavily through the BRI, which all South Asian countries except Bhutan and India are part of. This has put Beijing and New Delhi in direct competition, engaging in a geoeconomic rivalry to gain influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Pakistan is key in this context, given the historical enmity with India. Sino-Pakistan relations have a solid foundation dating back to the Cold War and they have seen further strengthening since 2015 with the establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a major component of the BRI. Due to Pakistan’s recurring economic and political turmoil, however, the success of this endeavor and, therefore, of bilateral economic relations, has been called into question.

China’s influence in South Asia also extends to the Indian Ocean, covering the island nations of Sri Lanka and Maldives. These countries’ political landscapes are in a constant state of flux, with the upcoming national elections taking place later this year set to yet again impact China and India’s relations with them.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh – despite its historic ties to India – has increasingly been engaging in defense cooperation with China, which was the largest supplier of arms to the country for the period between 2010 and 2020, amounting to 73.6 percent of Dhaka’s foreign military acquisitions. In contrast, Bhutan has no diplomatic relations with Beijing and the 2017 Doklam stand-off has only further aggravated the sensitivity of border issues between the two countries.

Overall, India has been forced to rethink its traditional policy of non-alignment due to China’s expanding presence around its disputed borders, its close ties with Russia, and increased involvement in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. As a result, New Delhi has sought to bolster relations with actors that share similar strategic objectives, particularly in the security realm.

Enlarging Security and Economic Cooperation

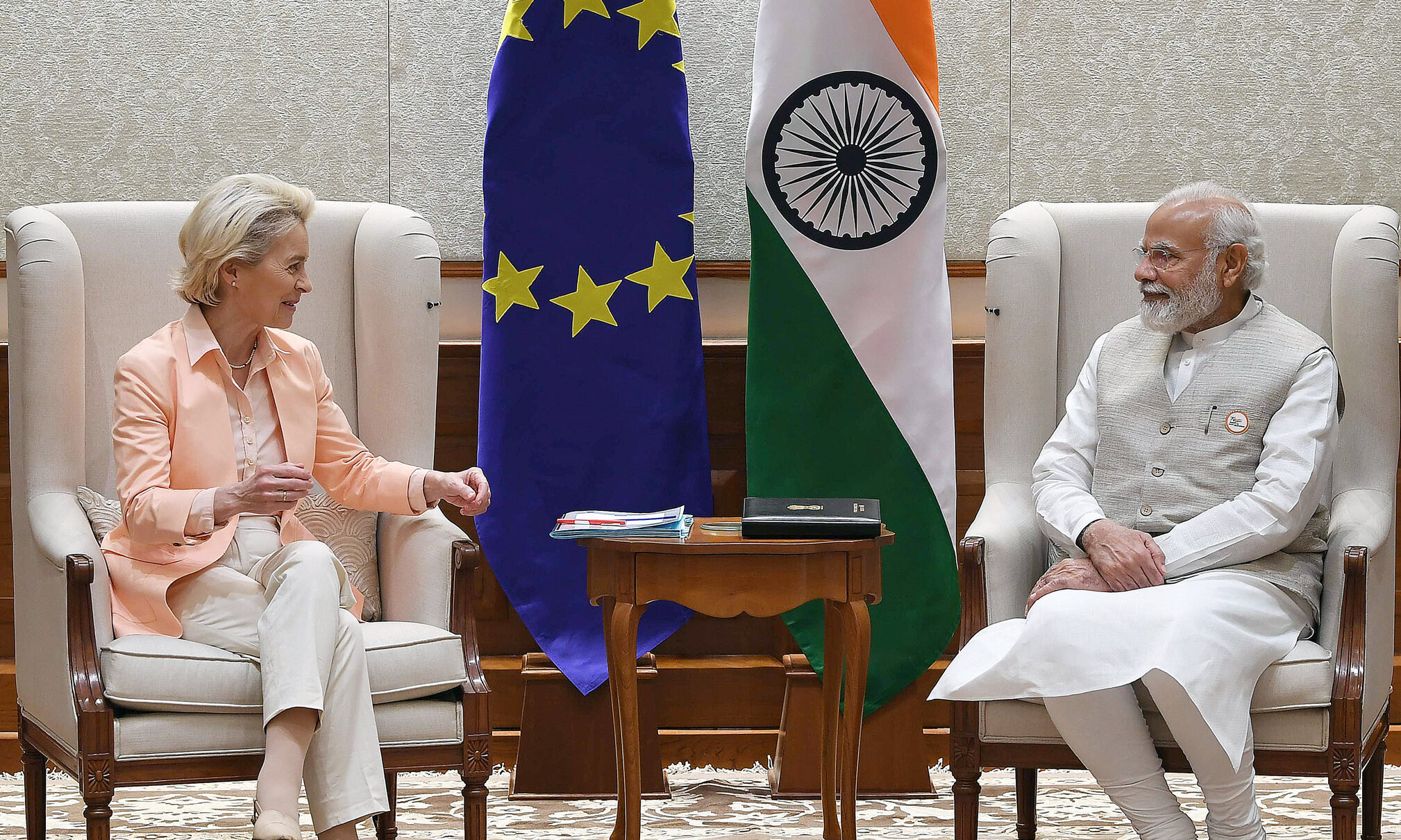

One of the key actors eyed by New Delhi is the EU. The first-ever EU-India Security and Defense Consultations were held in June 2022 in Brussels, heralding a new phase in bilateral engagement. During these consultations, both parties discussed ways to increase cooperation in the “co-development and co-production of defense equipment, including India’s participation in PESCO.”

Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) is a legal framework under the EU’s security and defense policy, designed to enhance defense cooperation among member states who wish to take it further. The inclusion of PESCO in these talks illustrates the potential for upgrading the cooperation in this field between the two partners, particularly given India’s overreliance on Russia for arms and ammunition. As such, security cooperation is likely to become an increasingly prominent component of the EU-India relationship in the future.

However, this is but a part of the larger picture. Negotiations for an EU-India Free Trade Agreement were relaunched in June 2022, alongside the launch of the Trade and Technology Council, a bilateral forum that marks a new phase of bilateral cooperation. This is partly due to the mirror effect of the Sino-Russian alignment, as the EU is looking to lessen its reliance on China, and India is trying to reduce its dependencies on both Russia and China in terms of military supplies and import reliance respectively.

In this context, India’s strategic partnership with France is a significant catalyst for positive developments in EU-India relations. Between 2017 and 2021, France was India’s second-largest arms supplier, after Russia and before the US. This relationship is unique and, in some ways, even stronger than the one with the US – a recent survey revealed that the US is perceived as the second-most significant security threat for India, after China, even surpassing India’s historic nemesis Pakistan. Despite the shared concern over China, there is still considerable reluctance from New Delhi towards Washington, thus making France a potential key partner in reducing India’s reliance on Russia.

Finally, maritime security is an area of great potential for deepening EU-India relations. The security environment in the Indo-Pacific is becoming increasingly unstable and ‘crowded’ due to traditional security trends such as increased military budgets, naval build-ups and acquisition of anti-ship missiles in the region, as well as non-traditional security trends such as global warming and competition over marine resources. EU-India relations in this field have been strengthened through the first-ever joint naval exercises held in June 2021 and the establishment of a regular security dialogue. More recently, at the EU Indo-Pacific Ministerial Forum held in Stockholm in May, Indian Foreign Minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, explicitly invited the EU to join the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative, paving the way for a more comprehensive dialogue on the Indo-Pacific.

Gaining a Better Insight into India’s Foreign Policy

The multiple channels of communication set up by the two sides are critical in allowing India to gain a better understanding of Europe’s security situation, and for Europe to grasp India’s concerns in its neighborhood and the Indo-Pacific. Upgrading the knowledge on India and analyzing the impact of Sino-Indian relations on EU-India ties will improve predictability and reliability of the EU-India relationship as a whole.

The EU should take a stronger, more resolute stance on Sino-Indian relations, particularly regarding Sino-Indian border disputes to build trust with India. However, as Shashi Taroor has pointed out, India also needs to do its part. Given its current stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, New Delhi cannot expect the EU to break its mostly apathetic attitude when China decides to redraw the Sino-Indian borders again. As the war in Ukraine continues, we will see to what extent the EU and India are able to act on their shared concerns.

Written by

Patrizia Cogo

PatriziaCogoPatrizia Cogo Morales is Project Manager and Research Assistant at the Elcano Royal Institute’s Office in Brussels. She also works as Project Officer at the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy of the Brussels School of Governance. Previously, she worked at the EsadeGeo-Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics within the team of Dr. Javier Solana. She is also Lead Co-founder and was President of the network European Guanxi. Her research interests include EU-China relations, Indian foreign policy, and the security dynamics in the Indo-Pacific.