Under President Biden, the United States has advanced its “small yard, high fence” strategy to curb China’s progress in advanced semiconductor manufacturing. This approach relies heavily on export controls targeting critical chip technologies. Key measures include restrictions on semiconductor manufacturing equipment – especially EUV and advanced DUV lithography tools – as well as controls on US persons involved in these technologies. Although EUV and DUV machines are produced by Dutch firms, they contain US-origin technology and therefore fall under the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR). Additionally, the US has engaged in diplomatic efforts to persuade the Dutch government to impose its own export restrictions on domestic suppliers. Within this tightly defined “small yard,” Chinese industry leaders such as SMIC and Huawei have found it increasingly difficult to sustain their previous pace of advancement in leading-edge process nodes.

US Export Controls and China’s Weakness in Advanced Semiconductors

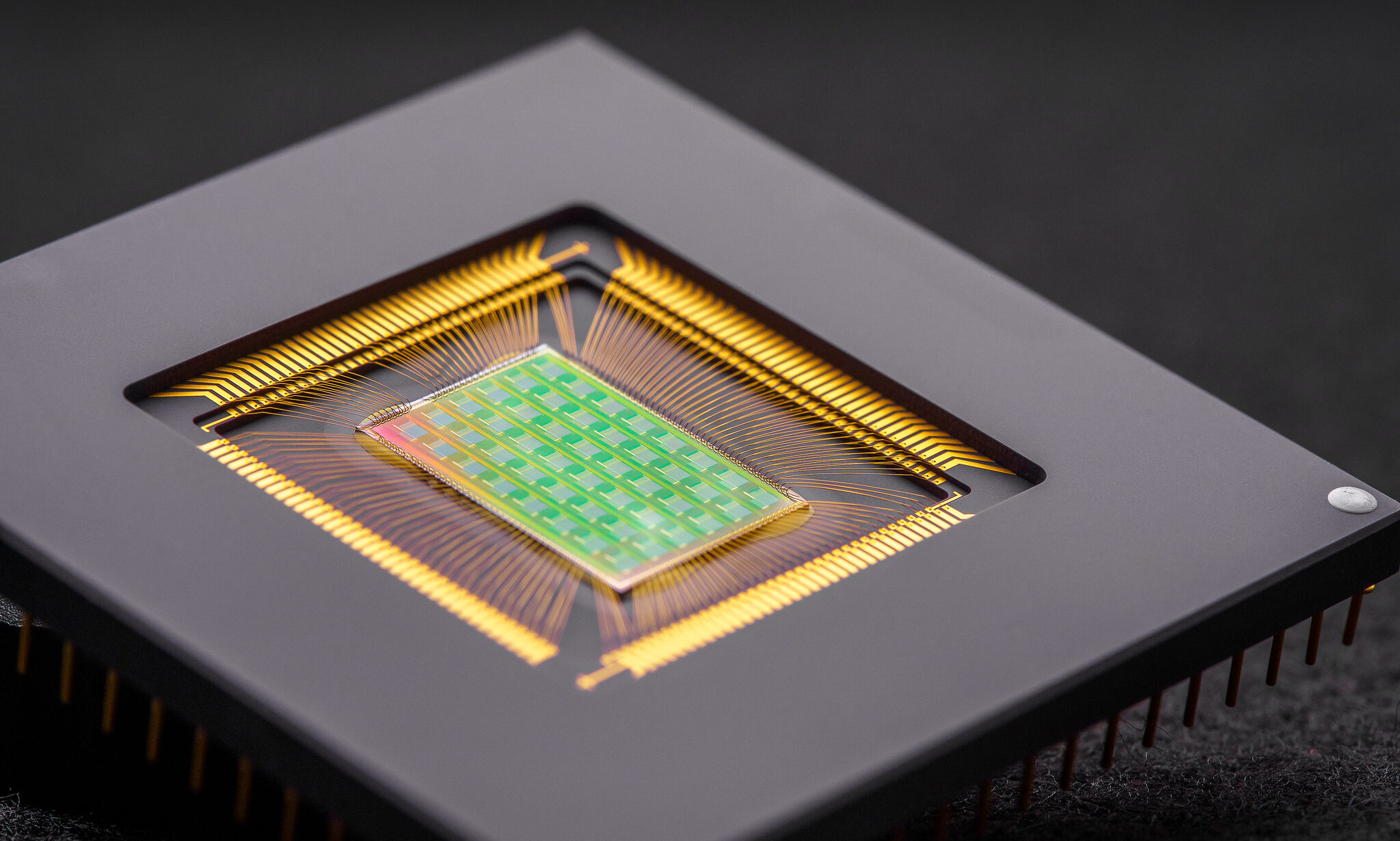

From both technological and capacity-expansion perspectives, these US export controls are having clear effects. According to Taiwan-based market intelligence firm TrendForce, China accounted for just 6 percent of global advanced semiconductor manufacturing capacity in 2023. Despite mobilizing vast national resources, China has made only limited progress, constrained by chokepoint technologies dominated by US-led tech democracies. By 2027, China’s share is projected to grow modestly to 8 percent. TrendForce defines “advanced nodes” as 16/14nm and below. While SMIC has reportedly achieved 7nm production and is targeting 5nm, yields remain only about one-third of Taiwan’s TSMC, resulting in significantly higher production costs.

This yield gap stems from SMIC’s reliance on traditional DUV lithography with multiple patterning – necessitated by export controls – where each additional exposure increases defect risks and limits yield. In contrast, TSMC is projected to achieve 2nm production by 2025, with 1.6/1.4nm nodes and backside power delivery on the horizon. Compared to Taiwan, China remains at least two to three generations behind in advanced chip technology.

The Centrality of Taiwan and China’s Strength in Mature-Node Chips

Taiwan stands as the most efficient hub for developing and producing advanced semiconductor technologies. It is also a vital driver of global AI computing power. No level of Chinese military intimidation can change this fact. In 2021, Taiwan held 71 percent of the world’s advanced process capacity. Although the US, China, Japan, and South Korea are expanding their own capabilities, Taiwan is projected to retain 58 percent of global advanced capacity by 2030, preserving its role as the world’s premier center for cutting-edge chip manufacturing. This centrality is one reason why leading AI chip designer NVIDIA regularly collaborates with Taiwan and recently announced plans to establish a new regional headquarters in Taipei.

To meet surging demand, TSMC held a joint press conference with President Trump in March 2025 to announce an additional $100 billion investment in US expansion, bringing its total US investment to $165 billion. However, by 2035, over 80 percent of TSMC’s production capacity is still expected to remain in Taiwan. Taiwan’s advantages – namely, its world-class industrial infrastructure, a robust talent pool, and highly efficient operations – make it irreplaceable. While the US will become a critical extension of Taiwan’s capabilities, it will not supplant Taiwan’s central role in the global chip supply chain.

A more immediate threat to Taiwan’s semiconductor industry comes from China’s aggressive strategy in mature-node chips. Unlike advanced-node technologies, mature-node processes are not easily constrained by export controls, as they do not rely heavily on US-origin technology. Yet mature-node chips play a foundational role in modern life, underpinning cybersecurity, data privacy, economic infrastructure, and national defense. Although not classified as high-tech, these chips account for over 95 percent of global semiconductor applications and form the backbone of 99.5 percent of US defense systems.

China’s approach extends well beyond subsidies. On one front, it drives downstream demand by promoting industries such as electric vehicles, renewable energy, displays, and telecom equipment, all of which rely on mature-node chips. On another front, it implements a distinct industrial policy model known as the Pseudo-IDM Model. Unlike traditional Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs) that vertically integrate operations within a single firm, China’s state-led model delegates different stages of the semiconductor supply chain to designated “national champion” firms. Central and local governments coordinate efforts – providing subsidies, financing, infrastructure, and procurement incentives – to systematically build vertically integrated ecosystems capable of flooding global markets with low-cost chips and products.

As these state-backed firms expand globally, they compress margins for international competitors, reduce their market share, and discourage further R&D investment. This not only weakens the resilience of democratic supply chains but also increases global dependence on Chinese technology. By 2024, China had already captured 34 percent of the mature-node chip market, second only to Taiwan’s 43 percent. By 2027, China’s share is projected to rise to 47 percent, while Taiwan’s drops to 36 percent and the US remains stagnant at 4 percent. Taiwan’s leadership position in this domain is at risk of being eclipsed. This is not mere business rivalry – it is a strategic encirclement by a state-directed campaign. And the consequences will ripple beyond Taiwan. Tech democracies globally will face the risks of overdependence on Chinese supply chains.

A Path Forward: Deepening Democratic Tech Alliances

These developments underscore the urgency of a comprehensive, multilateral response. In the advanced-node arena, tech democracies must continue refining and enforcing export controls, given their proven impact. In the mature-node domain, efforts should target critical chokepoints –such as photoresists and laser light sources – adding them to control lists. The United States should also lead in establishing a transparency mechanism to track chip-related dependencies on China and develop plans to phase out Chinese components in sensitive sectors such as surveillance systems and defense applications.

In recent years, both the European Union and the United States have accelerated efforts to expand domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity. The US has prioritized advanced AI chips, while the EU has focused on mature-node technologies for automotive applications. Some critics see this trend as a threat to Taiwan’s semiconductor industry. However, I believe it represents a strategic opportunity for Taiwan to enter the next phase of development.

First, the US and EU remain major consumer markets and key hubs for the development of consumer technology applications. As Taiwanese manufacturers move closer to these markets, they will be better positioned to understand end-user needs, enabling them to drive technological innovation and optimize capacity management based on real-time demand. Second, cutting-edge fields like semiconductors and AI depend heavily on top-tier talent. The US and EU continue to lead in global research and education systems. By investing abroad, Taiwanese companies can enhance global brand recognition, improve management culture, and attract top scientific talent –bringing long-term benefits to their development and global competitiveness.

When it comes to the manufacturing expansion goals of the US and the EU, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry remains a critical – if not the only – enabler and partner. Without Taiwan’s sustained production efficiency and frontier innovation, Western industries could be forced to rely more heavily on China. Therefore, it is both logical and strategic for the US and EU to deepen cooperation with Taiwan’s semiconductor sector. Furthermore, drawing Taiwan more tightly into the core of the democratic alliance not only strengthens industrial ties, but also serves as a deterrent to Chinese aggression – helping preserve peace and stability in East Asia and beyond.

Written by

Min-Yen Chiang

Chiang Min-yen is the Deputy Director for Economic Security at a Taiwan-based think tank – the Research Institute for Democracy, Society and Emerging Technology (DSET).